Inhibition in children predicts aggression

GSE research shows surprising findings

It’s time to pay attention to the unsqueaky wheel.

While bullies, braggarts, and loudmouths tend to grab the spotlight, their quiet, withdrawn classmates may be even more troubled, according to a new study by researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (GSE) and Brandeis University.

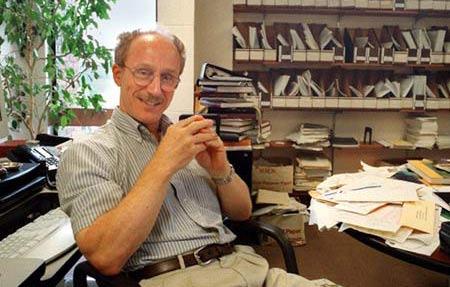

The study, led by the GSE’s Charles Bigelow Professor of Education Kurt Fischer and Brandeis University psychology professor Malcolm Watson, found that one of the strongest indicators of violence and aggression in children – second only to violence in the family – is their level of inhibition or social withdrawal.

The researchers tracked a socioeconomically and racially mixed group of 440 children from Springfield, Mass., over seven years.

“Our goal was to try to look at family and personality factors that contribute to aggression problems,” said Fischer, director of the GSE’s Mind, Brain and Education program.

Indeed, the research found that a family factor – violence in the home – was by far the strongest indicator of aggression in children, outweighing other factors like socioeconomic status, race, or gender. While this was expected, the second strongest predictor of aggression and violence – having an inhibited temperament or personality – was more surprising.

“Inhibition stood alone as the one personality characteristic that predicted aggression, which suggests possible connections with the isolated, alienated children who have committed school attacks,” said Fischer.

Lessons from school violence

The study, funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, collected data from four waves of interviews with 7-to 13-year-old children and their mothers. Questions probed the gamut of violence and aggression, from yelling to physical fighting to using weapons. Mothers and children self-reported and reported on the other, so researchers could corroborate their findings for a fuller picture of home life and the child’s personality.

While previous work indicated that family violence played a major role in children’s aggression, Fischer said his research team was impressed at the strength of its effect, which he called “whopping.”

“It’s as big an effect as you’ll ever get in one of these studies,” said Fischer.

Its dominance over other factors also surprised the researchers.

“Being poor, being black, being Hispanic, being male, none of those things predict very well for general levels of aggression in our sample,” he said.

For Fischer, an expert on cognitive and emotional development, the findings on inhibition predicting aggression were not a shock. In the clinical practice of psychology, he said, it’s well known that children who are quiet and withdrawn are often troubled.

“That’s considered a warning in the clinical literature,” he said.

Fischer also drew his hypothesis from the school shootings of the late 1990s, which challenged his and many others’ notions of school troublemakers. The Columbine shooting, in particular, had a personal as well as a professional impact on him: He and his family lived in a nearby Denver suburb at the time and his son knew one of the girls who was killed.

“People began to see more broadly that most of the school shooters ä are not blatantly violent people,” he said. “They’re people who are kind of withdrawn, who don’t have any friends, who are kind of quiet, and then suddenly there’s this violent act.”

Beyond shyness

Fischer is quick to point out that the inhibition the research points to is not the same as shyness, which most people report feeling at least some of the time.

“We’re talking about the kid or the adult who’s very introverted, or inhibited, and not very comfortable in novel situations, especially with people they don’t know or situations that are unfamiliar to them,” he said. In those novel situations, the inhibited person will react emotionally and withdraw.

“The vast majority of inhibited kids, withdrawn kids, are not ever going to become violent, dangerous kids,” he said, although many of them will struggle with new situations and emotional reactivity.

Even the majority of kids from violent families will not become seriously violent. They may, however, be more prone to aggressive behavior, like hitting their kids.

Still, said Fischer, there are important lessons that parents, teachers, and caregivers can draw from the study. Adults should be on the lookout for kids who are withdrawn as well as those who come from home situations where there is violence, whether directed toward the child or not.

Intervening with families to help eliminate the stress that’s causing the violence is important, Fischer said, as is helping inhibited kids engage with other people and build relationships. Sometimes, it’s as easy as making a connection with a troubled kid.

“There’s a whole lot of work with kids from troubled environments that shows that if they have one good relationship with somebody, it’s an enormous protective effect,” Fischer said.

Fischer and the researchers are hoping to fund one more round of interviews, which will follow some of the kids into legal adulthood, an age when criminal records become accessible and when many psychological disorders present themselves. He’s also forging partnerships with groups at Harvard and in the community to apply this research to other work on violence and children.

As a flurry of media interest spreads the study’s findings from the ivory tower of academic research to parents and educators, Fischer is hopeful that it will change the way adults interact with those quiet, withdrawn kids who never slap their siblings or disrupt classrooms.

“What the teacher or the counselor or the vice principal needs to be doing is to pay attention to the very quiet, unsqueaky wheel,” he said. “Those kids are at greater risk for a whole lot of things besides violence.”