Zwick ’74 talks art, film, politics

Producer/director accepts distinguished alumnus award

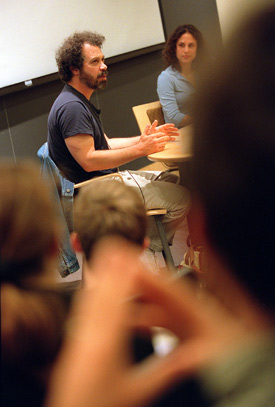

Dressed in a T-shirt, jeans, and sneakers, the youthful-looking Edward Zwick ’74 was scarcely distinguishable from the Harvard undergraduates who came last Friday (May 3) to hear him speak.

But while Zwick may dress like a kid, there is no disguising his mature accomplishments as a producer/director/writer in television and movies. His résumé speaks for itself: He produced “I Am Sam,” “Traffic,” and “Shakespeare in Love,” directed “The Siege,” “Courage Under Fire,” and “Glory,” and, with his professional partner Marshall Herskovits, played a principal role in producing, writing, and directing the television shows “Family,” “thirtysomething,” “My So-Called Life,” and “Once and Again.”

On May 2, Zwick participated in a discussion titled “Pop Politics: When Art, Film and Politics Collide” moderated by Institute of Politics Fellow Callie Crossley. On May 3, he received a distinguished alumnus award presented by the Harvard Entertainment Association (HEA) and discussed his career. His visit was sponsored jointly by the HEA and the Office for the Arts.

Zwick spoke about his undergraduate participation in the Harvard-Radcliffe Drama Club and of the times he and his fellow students were allowed to “run amok” in the Loeb Drama Center. But he added that the most important lessons he learned at Harvard were not artistic but organizational.

“What I learned here was how to work within large, complex institutions and how to manipulate them for your own ends.”

He also spent a lot of time seeing movies at the Brattle Theatre and the late, lamented Orson Welles Cinema. But as an undergraduate, he was “in denial about how important movies were to me.”

That denial broke down after spending a postgraduate year in Paris, again spending much of his time in movie theaters. His goals clearer, Zwick moved to California and enrolled in the American Film Institute.

“I can’t honestly say I understood what I learned there until many years afterward. I was interested, but I didn’t know how it pertained to me and my interests,” Zwick said. He added that as he has grown older he has become increasingly able to profit from those early lessons.

Zwick’s entry into the movie business was through writing. He described the next five years as “time in the wilderness,” which appeared to have a coherent direction only in retrospect. His assignments included writing a script for a film about the Kentucky Derby by a filmmaking team that couldn’t afford to send him to Kentucky, forcing him to become wildly inventive. Eventually, his growing reputation as a writer gave him enough leverage in the industry to get a job directing.

Zwick described finding his own creative voice as a process of getting over inhibitions and critical assumptions.

“It’s a paradox that once you discover something within yourself that’s deeply personal, it becomes universal,” he said.

Choosing a project is also a very personal thing.

“There’s a feeling when you read a story of the hair standing up on the back of your neck. It’s hard to describe. You know it when you feel it.”

Zwick said he had that feeling when he read a magazine article about Robert Gould Shaw, the young white officer who died fighting with the African-American 54th regiment in the Civil War. That experience led to the making of the film “Glory.”

“I tried to make a film that would recapitulate the experience of reading that article,” he said.

Zwick spoke about the extensive research he did for that film, then explained that in many scenes he had to sacrifice strict authenticity for artistic effect. He showed a clip from the film depicting the regiment’s first encounter, the Battle of James Island.

Zwick described how he reduced the number of men on both sides and halved the distance between them in order to increase the dramatic impact.

“Every moment in a movie is a concession to something you know is true.”

In “Traffic,” on the other hand, Zwick tried to incorporate a gritty authenticity, even if that meant antagonizing those who were expecting a clear anti-drug message. To illustrate, he showed a scene in which a group of students from an elite prep school spend an afternoon taking drugs.

“We realized that if we were going to up the octane of truth, we had to show that taking drugs is fun, sexy, and that smart kids do it, and that’s something that flies right in the face of appropriateness and decorum.”

Zwick spoke about working with actors, making an important distinction between stage and film acting.

“As a stage director, you’re weaning the actors. You’re empowering them to do the play without you. In film, you only need to get it right once, and it doesn’t matter how you do it. It’s utterly symbiotic.”

But at the same time, directing films has given Zwick the “astonishing blessing of working with people at the top of their fields.”

In collaborating with such talents – Zwick mentioned Morgan Freeman and Sean Penn – his aim is to “create an environment where these enormously talented people can do their best work. Often I’m thinking, how little do I need to do and still get what I need?”