‘What’s in a name?’

Charity Bell balances academics, foster parenting

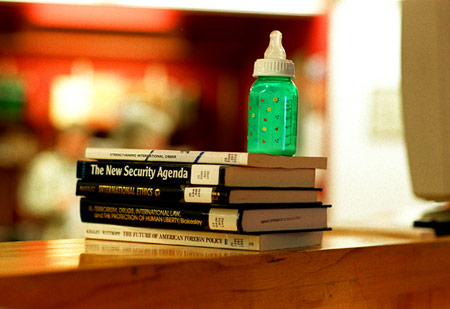

Sitting in a Harvard Square café in front of a half-eaten bagel and a Mountain Dew, Charity Bell could be any young mother, cradling a 3-month-old in one hand and a baby bottle in the other.

But Bell isn’t just any young mother, she’s a student at the Kennedy School of Government and an “emergency foster parent,” juggling the twin sleep-depriving roles of graduate student and new mom.

And her baby isn’t just any little girl. Withdrawing from methadone, not charming doting relatives, is her first task in life, compliments of her birth mother’s drug habit.

By all accounts, Bell is rare among college students, piling the weighty chores of child care on top of the course load of her master’s in public administration program. Unfortunately, that rarity is not shared by the children she has cared for. They – 36 since March 2000 – are all too common.

Joy Cochran, family resource coordinator for the Massachusetts Department of Social Services’ Boston Region, said Bell is unique in several ways. Not only does she lug the kids along to class with her, but, 28 and single, she’s younger than most foster parents and handling the challenge alone. Cochran said Bell’s ability to keep the babies with her all day helps the children through a tough time when they would otherwise be put in day care or shuffled between providers.

“I don’t think many foster parents are taking babies to class,” Cochran said. “I think it’s fabulous.”

Bell is one of just four emergency foster parents in DSS’s (Department of Social Services’) Boston Region. DSS workers call Bell and the three other emergency parents “hot line” families, because the DSS can call them days, nights, weekends, and holidays to take in homeless, abused, and abandoned children at a moment’s notice.

The children stay with Bell for varying lengths of time. Sometimes the placement is short, arriving at night and staying just long enough for DSS workers to get to the office in the morning to find a permanent placement. Other times the placements are longer, such as the case of Joshua, who stayed with Bell for three months.

“When Joshua left after three months, I was devastated,” Bell said. “Then the social worker said that in the first three months a baby learns what love is. That’s what keeps me going.”

Bell has had children as old as 2 but specializes in infants, particularly drug-addicted or premature babies. She has had as many as three children at a time. Once she had eight, including a set of twins, placed with her over one two-week holiday period.

Bell said she manages to juggle the responsibility of caring for fragile infants and her course load with the help of close friends and the understanding of Kennedy School faculty members who don’t object when she shows up to class with books – and baby – in tow.

Caffeine doesn’t hurt either.

“I don’t sleep. It makes it easier,” Bell said.

David King, associate professor in public policy at the Kennedy School, said Bell is providing a real-life case for students to study. He said students’ first reaction to Bell’s babies is “how cute,” but that view changes as they understand what has happened in the babies’ short lives.

“[Student reaction] gradually changes to ‘How in the world is this happening to this child?’ She and the child become an object lesson,” King said.

Bell’s situation provides lessons on social services, drug addiction, and parenting, King said. He also said he’d be surprised if anyone voiced objections to having a baby in the class.

“At the Kennedy School it’s more of an opportunity than an obstacle,” King said. “She’s certainly not your run-of-the-mill student.”

Another instructor, Ford Foundation Professor of Science and International Affairs Ashton Carter, said he only sees admiration for Bell from her peers.

“Both the students and I greatly admire what she’s doing,” Carter said. “I think that for her to be doing this on top of everything else she has to do, and for her to have this talent on top of her other talents, is a wonderful thing.”

It was Bell’s own eye-opening experience three years ago that made her into a foster parent. Newly home from a stint as a Peace Corps community health worker in Guinea, Bell was volunteering at New England Medical Center when she noticed that a sick little 2-year-old had been receiving no visitors. She visited the girl for five nights and then found out that she was a foster child the state couldn’t place. Bell contacted the state and began training to become a foster parent.

“I was horrified that no one would open their doors to this little 2-year-old girl,” Bell said.

Her outrage may have been boosted by perspective gained from the more family-friendly society in Guinea. She recalls explaining America’s foster system to people there and struggling to answer puzzled questions on why the children aren’t taken by grandparents, aunts, uncles, and other members of the extended family.

“That’s an indictment of America,” Bell said.

Bell’s involvement with children today may even have been foreshadowed by her experience in Africa. On her first night at her site, which was a three-day trip from the capital city of Conakry, someone banged on her door and summoned her to a woman in labor. Despite not understanding the local language and being trained in nutrition rather than midwifery, Bell delivered the baby.

“I figured it out,” Bell said. “It’s not that complicated.”

Bell, who once trained as an opera singer at the New England Conservatory, is uncertain about what course she’ll take after graduation. She believes the foster care system urgently needs reform and is trying to figure out the best way to effect change. One change would be figuring out how to encourage more people from higher socioeconomic groups to become foster parents. Because people from higher socioeconomic groups tend to be more politically active and have more resources, especially time, she said, that would make them a more powerful voice for the children in the system.

Bell said just doing what she’s doing now is important. Not only does it have an impact on the kids she tends, but she’s initiating discussions she hopes will increase understanding of the foster system.

Bell said the questions she gets indicate that many don’t understand the child welfare system. Some think she has 13 kids at home while others confuse foster parents – who provide transitional care – and permanent adoptive parents.

“I realized that people don’t have a clue. People don’t know what foster care is,” Bell said. “Suddenly I realized that it’s really important that people understand.”

People often tell her they could never do what she does, but Bell says that’s because they don’t understand the impact they could have on both individual children and on a range of societal problems linked to family breakdown, such as crime, teen pregnancy, and substance abuse.

Bell said there’s nothing awe-inspiring about what she does, just an awareness of the problems and a desire to do what she can to help. Anyone can make a difference, she said.

“The ripple effects are enormous,” Bell said. “If you want to make the future better for your kids, here it is. These are the kids that are going to be going to school with your kids.”