The tortuous road to Harper’s Ferry

New book looks at four 19th century ‘terrorists,’ two white, two black

On Oct. 16, 1859, John Brown and 21 men – 16 whites and five blacks – raided the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, W.Va., with the intention of distributing arms to Southern slaves and fomenting a violent uprising.

The attack failed. Militiamen surrounded the arsenal and several of Brown’s men, including two of his sons, died in the ensuing fight. The next day, U.S. Marines arrived and took Brown and his surviving co-conspirators prisoner. They were later hanged.

Even though Brown’s plan misfired, the event shocked the nation because the specter of a slave uprising was precisely what had been haunting slave owners ever since kidnapped Africans started arriving in America to supply forced plantation labor. And hardly anyone, including Northerners, could understand how a white man like Brown could sacrifice his life to liberate blacks. Brown was labeled insane by the press, a characterization that has largely stuck to this day.

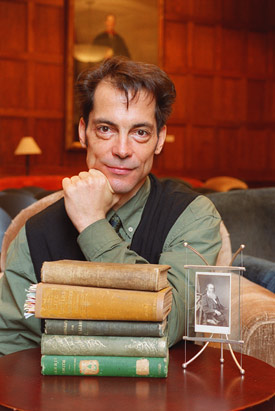

But there is more to the story, and more to Brown, than this simplified account would suggest. The charged and complex background to John Brown’s raid receives a full elaboration in a new book by John Stauffer, associate professor of English and American Civilization at Harvard.

The book, “The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race” (Harvard University Press, 2002), opens a window on the decade before the Civil War and reveals the thoughts, emotions, and relationships of black and white leaders on the leading edge of the abolitionist movement.

Certainly Brown was an extremist who went out in a blaze of glory, but even extremists must plod through a pre-blaze existence, and Brown was no exception. In Stauffer’s book, he emerges as a sensitive, morose boy, thrown into deep mourning by the death of a pet squirrel, who became a sternly idealistic patriarch dragging his large family through one business failure after another.

The restless Brown was unable to find peace or contentment until 1848 when he moved to the community of North Elba, N.Y., known by its inhabitants as Timbucto.

Timbucto was the creation of another radical abolitionist, Gerrit Smith. The son of a shrewd Yankee trader who made a fortune in the fur trade and invested his profits in land, Smith rebelled against his father, emulated Lord Byron, and dreamed of becoming a famous poet.

Instead, he found himself an extremely wealthy landowner, inheriting nearly a million acres in New York and Virginia. His wealth allowed him to become one of the 19th century’s greatest philanthropists, giving away 120,000 acres of land near Lake Placid to poor blacks, creating the community that came to be known as Timbucto, after the fabled cosmopolitan city in West Africa. He also spent enormous sums to purchase the freedom of Southern slaves and to help support numerous individuals and progressive groups.

Smith’s plan for Timbucto was not only to make the recipients of his charity economically self-sufficient, but also to empower them politically by giving them enough land to qualify them to vote.

It was to this community that John Brown came in 1848, promising to help his black neighbors learn to farm and attain self-sufficiency, a promise he largely kept, when he was not off fighting in the guerrilla war to keep Kansas free of slavery. During his years as a resident of Timbucto, he became a close friend of Smith, who helped him plan and finance the attack on Harper’s Ferry.

Stauffer’s book takes the form of a collective biography, tracing the interrelationships among these two men and two black abolitionist leaders, Frederick Douglass and James McCune Smith.

The charismatic Douglass became the best known of the four by virtue of his speeches, publications, and lifelong efforts to fashion a public persona. Born a slave, he was taught to read by his owner’s wife. He escaped to freedom in 1838 and within a few years became famous as an abolitionist speaker, joining William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society. He wrote voluminously, publishing four different versions of his autobiography. He also edited Frederick Douglass’ Paper (funded by Gerrit Smith), a leading abolitionist journal.

James McCune Smith was born in New York City and was freed from slavery as a result of the Emancipation Act of the state of New York. He attended the African Free School, which produced many other prominent black leaders. Denied admission to American medical schools, he traveled to Scotland and received a medical education at the University of Glasgow.

Upon returning to New York, he was lionized by the black community and quickly became a prominent black leader. A successful doctor with an interracial practice, he was also extremely well read in history and literature, and, in his own writings, employed an allusive and nuanced style reminiscent of Herman Melville. He got to know Gerrit Smith when the philanthropist asked him to become one of Timbucto’s trustees and to help select worthy black candidates for gifts of land.

Stauffer shows how these four men, two black and two white, learned to trust one another and to work intimately together in an era when most mainstream abolitionists accepted the idea that blacks were inherently inferior. The book’s title refers to the idea, common among these radical thinkers, that in order to cure the country’s racial ills, whites must change fundamentally and acquire “a black heart.”

Unlike mainstream abolitionists, many of whom supported schemes to send the country’s black population back to Africa under the assumption that whites could never accept the wholesale emancipation of blacks, these radical activists envisioned a peaceful multiracial society. Gerrit Smith, in fact, created such a society on his extensive land holdings around Peterboro, N.Y.

Unfortunately, the story does not have a happy ending. Inspired by apocalyptic “Bible politics,” the four men came increasingly to believe that the “sin” of slavery could be expiated only through the shedding of blood.

They justified violence by asserting that slavery was a crime and its perpetrators criminals. As Douglass wrote, “Men who live by robbing their fellow men of their labor and liberty … have voluntarily placed themselves beyond the laws of justice and honor, and have become only fitted for companionship with thieves and pirates – the common enemies of God and of all mankind.”

From today’s perspective, such ideas have the ring of universal truth. But in the antebellum world in which these men were operating, a world in which slavery supported a vast and lucrative plantation economy, their beliefs made them dangerous extremists, not unlike the Muslim suicide bombers and pro-life assassins of today.

After John Brown’s raid ended in failure, Gerrit Smith became fearful that his own part in the plan would become public, and he suffered a nervous breakdown. He escaped being indicted as a co-conspirator, but he did spend time in an insane asylum, where he was treated with brandy, marijuana, and opium.

The same authorities that let Smith off the hook went after Douglass with a vengeance, even though the only evidence for his complicity in the raid (he had, in fact, taken part in the planning phase) was one highly ambiguous letter. He was forced to flee to Canada to avoid prosecution. McCune Smith had also been a co-conspirator, but covered his tracks well and was not indicted.

Gerrit Smith eventually recovered his wits, but at the expense of his politics. He renounced the apocalyptic thinking that caused him to believe that Brown’s raid would actually succeed and distanced himself from his black friends.

McCune Smith took Gerrit Smith to task for his backsliding and conservatism, scolding him in a series of letters as the Civil War threatened to tear the nation apart. McCune Smith barely survived the end of that conflict, however. He died of heart disease at the age of 52.

Frederick Douglass survived until 1895, becoming the most famous black man in America, but he too gave up his radical politics. He advised Lincoln during the war and became a loyal member of the Republican Party, espousing the idea that racial equality would be achieved through legislation rather than bloodshed.

Such rightward shifts are not unusual in any age, and Stauffer’s narrative might be construed as an illustration of the idea that no political movement so radical in its methods and so conspicuously ahead of its time can succeed.

But the story of these four unusual men can also be seen as an example of the ability of human beings to shed their prejudices and work in harmony and trust toward a mutual goal, even if that goal is not to be reached within their lifetimes.