The living streets of Havana

Coyula wants to preserve his home’s architectural integrity

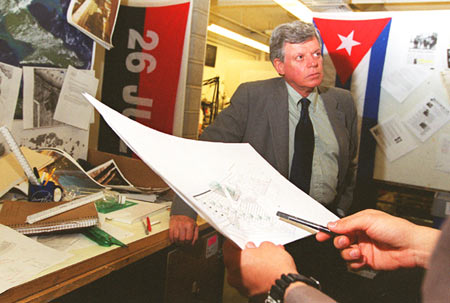

Mario Coyula takes pride in his country’s ability to survive.

“After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Havana was filled with journalists, mostly from the United States, who wanted to see if Cuba would also fall. It didn’t, and that was a great achievement.”

Coyula, an architect and urban design specialist, is the Robert F. Kennedy Visiting Professor in Latin American Studies – the first to come from Cuba. He is teaching at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) during the spring semester.

Although Cuba survived, the sudden interruption of aid from the Soviet Union had disastrous consequences, Coyula said. Maintenance of buildings and streets was drastically curtailed, as were services such as garbage collection and public transportation. Education and health care continued, although they too suffered from the severe funding cuts.

The recovery from this low point has been modest but steady, aided by the increase in tourism and foreign investment. The inflow of money promises to continue, bringing about greater changes in Cuba’s environment and infrastructure. Coyula wants to ensure that these changes are beneficial.

“For a long time we had a problem with lack of money. Now we are facing a problem with money coming too fast. Now is the time to vaccinate ourselves. We must learn how communities and planning authorities can avoid bad projects that destroy the built fabric and the social fabric.”

Coyula is teaching two courses during the spring semester. With GSD Professor Leland Cott, he is co-teaching a studio on el Malecón, the seven-kilometer-long oceanfront boulevard that is Havana’s premier open space. The studio is exploring issues of historic preservation as well as the design of housing and community development.

Coyula is also teaching a semester-long course on “Havana’s Challenges and Opportunities” that explores the ways Cuba can preserve its social achievements while strengthening its economy, so as to compete in today’s globalized world. The course also deals with making the most of Havana’s natural, built, and social resources without destroying or distorting them.

This is the third studio course Coyula has taught with Cott, although for the first two he served only as the studio’s Cuban contact, guiding students during a field trip to Havana and visiting the GSD for a brief critique of student work. Cott, who is on the faculty committee of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, nominated Coyula to be an RFK Visiting Professor and was thus instrumental in bringing him to Harvard for this semester-long residence.

“He’s a very good studio teacher,” Cott said of his co-instructor. “He brings a great deal of sophistication to the course as well as a different perspective from the one students are accustomed to. What they’re getting is the best that Cuba has to offer as an urbanist and an architect.”

In Cuba, Coyula is a professor de meritu (the equivalent of a University Professor) at Havana’s Instituto Politécnico José Antonio Echeverría and a former director of the school of architecture. He is also the former president of Havana’s landmarks commission and former director of architecture and urbanism in Havana. With Roberto Segre and Joseph Scarpaci, he is co-author of “Havana: Two Faces of the Antillean Metropolis” (John Wiley, 1997), which will be republished this year in an updated edition by the North Carolina University Press. In 2001, he received the Cuban National Prize in Architecture, a lifetime award.

Next year, Coyula and Cott plan to offer another studio at the GSD focusing on La Rampa, the starting point of Havana’s main artery, an area characterized by buildings from the 1950s and ’60s that Coyula calls the most modern and alive section of the city.

Coyula emphasizes that although Havana’s infrastructure has suffered as a result of its unique political history, it is still the major metropolis of the Caribbean and a city with many extraordinary buildings and neighborhoods, dating from the 16th to the 20th century.

It also has a look and feel all its own, a low-rise city marked by an abundance of columned porticoes along the main streets that act as buffers between the indoor and outdoor spaces, protecting pedestrians from sun and rain. There are also many porches and balconies overlooking the streets, which contribute to the city’s lively, human quality.

“The streets are always alive,” said Coyula. “People set up tables in the street for playing dominoes. There is always a corner grocery where people hang out. It is an atmosphere in which the social classes are leveled.”

Unlike many cities in the United States, where poor people are forced out of their neighborhoods by gentrification, almost the opposite process has taken place in Havana. There, the upscale neighborhoods were abandoned as wealthy residents fled Castro’s revolution, leaving their mansions to be occupied by the poor and lower middle class.

Coyula fears that the charm and beauty of the built environment may be threatened in this new era of foreign investment as contractors rush to fill the cityscape with trite and characterless modern buildings.

“Architecture has been kidnapped by the contractors. I believe it should return to the world of culture.”

He also fears for the changes that the new influx of tourists may bring to the island. For many Cubans, tourist dollars are a welcome addition to the country’s main industry – growing and processing sugar cane. But Coyula believes Cuba has more to offer than its sunny beaches, palm trees, and rum drinks.

“Tourism has many dangers,” he said. “It is dangerous to rely on any one thing. Tourism also develops a servant mentality. Already in Havana we’re seeing prostitutes again.”

Instead of emphasizing the “sun and sand” aspect of Cuban tourism, Coyula would like to see tourists traveling to Cuba to experience the island’s excellent music, art, and ballet. He would also like to see Cuba make better use of its human capital and its built environment.

“The country has a very skilled and educated population. Some people say, how are we going to feed 11 million mouths? I would reverse that thinking, see them as a resource. The same with the built environment. The conventional attitude was to say it can’t be preserved because it was too heavy a burden on the back of the government. But my attitude is that we can find ways to make the built environment pay for itself. That is already happening in Old Havana and some other Cuban historic centers.”