Researchers aim to understand school shootings

Paducah, Ky., Edinboro, Penn., Jonesboro, Ark., Littleton, Colo.

Once unremarkable small towns and suburbs, these communities were catapulted into news headlines and the national consciousness following violent school shootings in the late 1990s. Their now-familiar names prompt the same questions: Why here? Why our kids? What can be done?

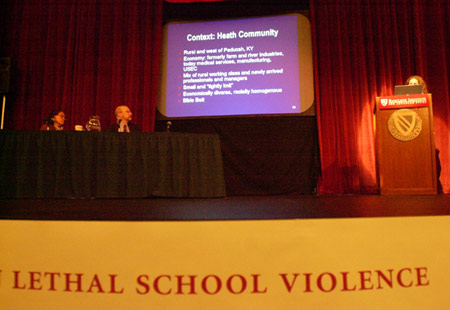

Educators, policy-makers, law enforcement officials, and adolescent-development specialists came to the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study last Tuesday (May 21) to probe these and other questions at the National Conference on Lethal School Violence. The forum was organized by the National Academies of Science (NAS), the Kennedy School of Government (KSG), Graduate School of Education (GSE), and Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

The centerpiece of the conference was the report “Deadly Lessons: Understanding Lethal School Violence,” a qualitative and quantitative study of incidents of lethal school shootings released by the NAS May 17. The report, commissioned by Congress, studied six incidences of lethal school violence that occurred in the 1990s.

In addition, Harvard Provost Steven Hyman, Graduate School of Education Professor Richard Elmore, and Boston Police Commissioner Paul Evans offered mental health, educational, and police perspectives on lethal school violence, respectively.

While the conference offered no quick fixes or easy answers, the researchers found that spotlight-grabbing culprits such as family instability and violent media images played a role in some but not all of the shootings.

More common and disturbing trends surrounding the shootings were easy access to guns and the increasingly fragile mental health of the shooters.

Yet while the shooters exhibited warning signs, these signs were, for the most part, ignored by adults. Enhancing screening for student mental health problems and bridging the communication divide between students and the adults responsible for them may prevent school shootings, the researchers found.

“Our best shot at prevention … is getting beyond the wall” that separates adults and students, said Radcliffe Dean of Social Science and Malcolm Wiener Professorship of Urban Studies at the Kennedy School of Government Katherine S. Newman, who led two of the study’s research teams.

Flying beneath the radar

Newman presented her research on the December 1997 shooting in West Paducah, Ky., one of three in-depth case studies featured at the conference.

The circumstances in the case of Paducah freshman Michael Carneal, who killed three students and wounded five when he opened fire on a prayer group meeting in his high school lobby, epitomize the “How could it happen here?” reaction common to the suburban and rural shootings of the late-1990s.

Newman described Paducah as a small, tightly knit, religiously conservative town rich in the sought-after “social capital” of an involved community. The Carneal family, prominent and stable, “was almost exactly the opposite of a dysfunctional family,” she said.

Yet as he progressed through middle school to high school, Michael Carneal exhibited subtly disturbing signs: His grades slipped, he had minor discipline problems, he began to hang out with older kids in the “Goth” group.

His parents, while concerned about his grades, were defensive about his discipline problems, and school administrators had not identified him as a problem – a profile shared by many of the shooters, said Newman.

“In general, we find that the shooters, they tend to be flying right underneath that radar screen,” she said. “They are rarely people who have no history of disciplinary problems, but they are also not the first kid that any teacher or principal would say, ‘Oh, yes, I’m not surprised it was Johnny.’ They’re usually quite surprised it was Johnny.”

Like Michael Carneal, Andrew Wurst was under the radar before he shot two teachers and two students, killing teacher John J. Gillette, at his eighth-grade dinner-dance in Edinboro, Pa. Researcher William DeJong, professor at the Boston University School of Public Health and an adjunct professor at Harvard’s School of Public Health, called the 14-year-old “unremarkable.”

Wurst also exhibited signs of trouble, some even more overt than Carneal’s. His grades had also dropped; he showed signs of depression; and he used alcohol and marijuana. Wurst’s parents, whose marriage was troubled at the time of the 1998 shooting, noticed that he was emotionally “flat,” said DeJong, “but they didn’t think this was out of the ordinary. After all, he was a teenager.”

Wurst made threats and gave warnings that were, disturbingly, dismissed, DeJong said. A teacher overheard him plotting with another student but after reporting the incident to an administrator, never heard of it again.

The urban contrast

In the third case study, of two separate shootings in 1991 and 1992 in urban East New York, researcher Mindy Thompson Fullilove presented a scenario that stood in stark contrast to the shootings in Paducah and Edinboro.

Unlike those communities, East New York, which borders Brooklyn and Queens, suffered badly at the hands of civic neglect and misguided urban planning. The result, said Fullilove, a professor of clinical psychiatry and public health at Columbia University, was a culture of guns and violence.

“Being shot and being killed had become very much a part of the life experience,” she said.

The lethal violence in suburban and rural schools did indeed follow different patterns from the violence in the urban schools studied, said Mark H. Moore, Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice Policy and Management at the Kennedy School of Government and chair of the Case Studies of School Violence committee.

While the violence in inner-city schools, which occurred in the early 1990s, mirrored the violence in urban areas at that time, suburban and rural school shootings more similarly resembled the “rampage” shootings that occur in workplaces or public places, the researchers concluded.

Moore offered specific recommendations based on the case studies: Communities need to limit students’ unsupervised access to guns, attend to issues of adolescent mental health, and take seriously the warnings of students.

Still, he said, “rampage shootings are rare events. Every community is vulnerable, but virtually all communities will escape.”