‘Parachute radio’ comes to campus

At Lowell Lecture, Lydon extols global art of conversation

What the world needs now, according to former National Public Radio talk show host Christopher Lydon, is a really good chat.

Lydon, an icon in Boston public broadcasting, brought tales of globetrotting, talk-radio style, to the annual Lowell Lecture Tuesday night (May 7), jointly sponsored by the Extension School and the Lowell Institute of Boston.

Discussing “A Culture Trying to Happen,” Lydon offered up the same incisive, provocative, literate fare that won him legions of fans (many of whom packed Science Center C) during his seven-year gig as creator and host of the call-in show “The Connection” on WBUR-FM.

“I’m thinking about this less as a lecture than as a radio show with myself,” Lydon warned. Since he decamped from “The Connection” in 2001 after a much-publicized battle for ownership of the program with station management, Lydon has harnessed the Internet to have a conversation-without-borders with his faithful listeners and with new ones around the world.

For his Lowell Lecture, Lydon drew from recent radio junkets to Jamaica, Ghana, and Singapore, sponsored by Harvard Law School’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Lydon described his travels as “parachute radio” – he and a small production team dropped into each nation “like the proverbial Martian, saying ‘take me to your interesting talkers.’”

Hosting call-in talk shows for several weeks in each location, he said, he was “engaged in local chat but listening for global resonances.” His programs found global audiences, too, on his Web site (http://www.christopherlydon.org).

Lydon described Jamaica, Ghana, and Singapore, each of which shed British rule about 40 years ago, as “developing, underdeveloped and overdeveloped.” Yet common themes emerged from the other side of the microphone: America’s neo-imperialism, the gale force of globalization, cultural identity, the promise of the Internet.

And, he said, a ravenous appetite for conversation: “an interactive, live, noncommercial, anti-imperial, democratic exchange across the color lines, across the political line, across the poverty line.” This conversation, he said, embodies the “culture trying to happen.”

From his travels and talk, Lydon got a clear and distasteful view of America’s cultural and commercial imperialism, even more polarized since Sept. 11. “We want all the oil and we want all the air time,” he said critically.

He contrasted Singapore, with its obsession with newness, Hollywood gossip, Disneyland malls, and “kitsch … as a narcotic,” to the cultures of Jamaica and Ghana, economically poorer but wealthy with cultural identity.

Still, these cultures are not immune to imperialism, he said, describing the prominence of the electronic drum machine in Ghana, the land of the drum. But as one Ghanaian interviewee boasted about Africa’s advantage in the global marketplace: “Africa has all the content.”

The Internet, said Lydon, has great potential to serve this culture trying to happen. Ghana and Singapore stand in surprising contrast in their embrace of the Internet. While Africa hopes to leapfrog the Industrial Revolution to land squarely in the Internet’s infinite possibility, Singapore, although “wired to the nines,” is hamstrung by self-imposed cultural and political limitations.

Lydon described the Internet not as a place to which he was banished from radio but rather as a new environment that nurtures civil, open interchange.

“I think of us as building a new coral reef of conversation in a new sort of ocean,” he said.

And whether it’s carried on the Internet or talk radio, the essence of this culture trying to happen “is the many-layered magic, the grit, the variety, the dynamic range, the accent and the authenticity of free voices, vox humana,” he said. “Count me in on all we can do to liberate and extend all the powerful good and all the pleasures of that fabulous instrument.”

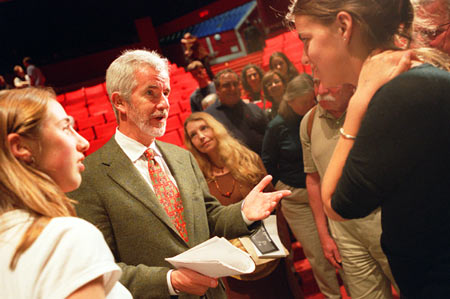

Lydon concluded his concise lecture with an expansive question-and-answer session, launched with a familiar invitation: “This is the moment when we go to our callers.” For nearly 45 minutes, he fielded questions from and engaged in conversation with audience members, many of them familiar as former regular callers to “The Connection.”

The conversation sprawled from globalization and America’s war on terrorism to consolidation of media ownership and the listener withdrawal symptoms that Lydon playfully dubbed “Connection Obsession Disorder.”

“There’s just so much to talk about out there,” said Lydon.