On awards, sales, innovation, and integrity

University Press’ secret to success: Publish books people want to read

When “The Ants” by E.O. Wilson and Bert Hölldobler won the 1991 Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction, there was little doubt that receiving this prestigious and coveted award exerted a positive effect on the book’s sales.

“We sold almost 30,000 copies,” said William Sisler, director of Harvard University Press (HUP), the book’s publisher. “Now, you know there just aren’t that many ant scientists out there.”

The success of “The Ants” illustrates what every book publisher knows – that winning an important award can turn even a seemingly specialized book into a best seller.

But what about a lesser award – say, for example, the Julia Cherry Spruill Prize for the Best Book on Southern Women, sponsored by the Southern Association for Women Historians? Last year, that prize went to an HUP book, “Born in Bondage: Growing up Enslaved in the Antebellum South” by Marie Jenkins Schwartz.

Just how much that prize has enhanced the book’s sales is difficult to calculate, but HUP is no less eager to garner smaller prizes than it is to bag big ones like the Pulitzer.

“In many areas, specialized prizes get the attention of those within the discipline. They’re also an indication to authors of the company they would be keeping if they joined our program,” Sisler said.

How literary prizes affect sales and other factors has become a topic of greater interest at HUP in recent years. This is because its books have been winning a greater share of honors than ever before.

For example, “Race and Reunion” by David Blight (2001), a book that describes how issues of slavery and civil rights that ignited the Civil War tended to get lost as the conflict became enshrined in the national memory, has earned no fewer than seven recent prizes. Among them are: the Bancroft Prize in History, the Frederick Douglass Prize, the Lincoln Prize, and the Merle Curti Intellectual History and Social History Awards.

A selected and highly arbitrary list of winners in other categories includes: “The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories” by John Heilbron, winner of the Pfizer Prize of the History of Science Society; “Trent and All That” by John W. O’Malley, winner of the Roland H. Bainton Book Prize, History and Theology Category; and “Facing East from Indian Country” by Daniel Richter, which looks at the colonization of North America from the Native American point of view. It has won the Louis Gottschalk Prize in Eighteenth Century History and is officially listed as a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History.

How does HUP do it? One way is by taking risks.

“We are interested in books that cross borders and break down barriers,” said Sisler.

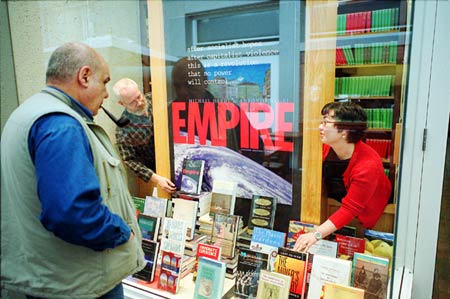

One example might be the recently published “Empire” by Michael Hardt, a Duke University literary theorist, and Antonio Negri, a scholar and political activist currently serving time in a prison in Rome. The book takes a sweeping, neo-Marxist look at the process of globalization. It was favorably reviewed in The New York Times Book Review and has since begun selling extremely well.

The hope is that sales of books like “Empire” and the soon-to-be-published “To Be the Poet” by Maxine Hong Kingston will help to support more specialized monographs, which often lose money.

But not all publishing gambles involve books by celebrity authors or those with controversial points of view. For example, consider a reference work like “Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World,” edited by G.W. Bowersock, Peter Brown, and Oleg Grabar (1999). The book was the winner of the 1999 Professional/Scholarly Publishing Award of the Association of American Publishers, History Category.

“It’s risky in a different way because it’s so expensive to produce,” Sisler said. “But if such books are done correctly, they can resonate and have staying power.”

Deciding which books to publish and which to forego has become increasingly crucial because of the changing nature of the retail end of the business. Small, independent booksellers are vanishing, replaced by large chains and online vendors. In the last year alone, the number of members of the American Booksellers Association dropped by 21 percent. As a result, stores that might carry specialized academic volumes are getting harder to find.

Library purchases of new books have decreased over the same period, often resulting in smaller sales. But one thing that has not changed is the fact that, traditionally, book publishers must buy back surplus stock from sellers at full price.

“The book business is in effect a consignment business,” Sisler said.

According to Sisler, HUP has been a leader in responding to these changes, streamlining its business practices and striving to operate effectively in the new electronic environment. But these efforts are only a small part of the Press’ efforts to stay competitive, he said.

“The most important thing is the quality of the books we publish. If you don’t have the books people want to read, all of the technical stuff isn’t going to make you successful.”