Crichton informative and candid at HMS

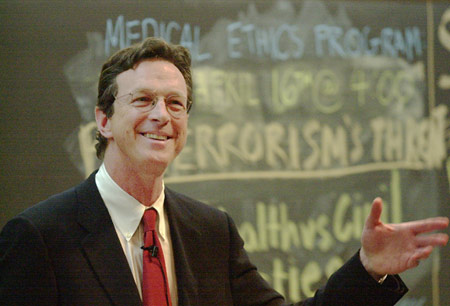

Michael Crichton ’64, HMS ’69, best-selling author and blockbuster director, came to Harvard Medical School Thursday, April 11, to deliver a lecture advertised as exploring the busy intersection of “The Media & Medicine.”

Instead, Crichton shared insider knowledge on Hollywood politics, making “ER,” and mechanical dinosaurs.

Crichton was cynical but unapologetic about the realities of creating popular culture. “People always ask me ‘Why are movies so bad?’ I know the answer to that,” he promised. “I can also tell you what happened to the intellectual content in ‘Jurassic Park’ … and what’s going to happen next on ‘ER.’”

Crichton’s talk was the third biannual W.H.R. Rivers Distinguished Lecture in Social Medicine, a series supported by a fund that bears his name.

The lanky, self-effacing author of “The Andromeda Strain” and “Timeline” told the audience – primarily medical students – that “it’s nice to be back at medical school, which is something you can feel after you’ve been away for several decades.”

Crichton, who said he tried repeatedly to drop out of medical school, never practiced medicine, choosing a career path that led him to Hollywood instead. Involved in some of Hollywood’s most popular movies, including “Coma” and “Jurassic Park,” Crichton offered his jaded if realistic perspective on the industry.

“Showbiz is a business,” he said. “It has lost very much contact with audiences and their needs and demands.”

Crichton de-glamorized moviemaking with tales of Steven Spielberg’s career path, explaining that even Hollywood’s most successful director had to kowtow to the studios, agreeing to make “Jurassic Park” so that they would let him direct the much weightier “Schindler’s List.”

“Someone like me, who’s quite a bit farther down in the pecking order, is always scrambling,” said Crichton.

The industry’s obsession with first-weekend box-office totals and the post-release foreign and video markets drives the content of movies. “The conditions of creativity have deteriorated substantially,” he said.

The making of ‘ER’

Paradoxically, Crichton said, one can win back creativity by avoiding a smash hit. “If you want to be completely left alone to do your movie, the best thing that can happen is that the studio or network doesn’t believe in it,” he said.

“ER,” the top-rated television drama for each of its eight seasons, was born of this paradox. Originally conceived as a movie script based on Crichton’s rotation at Massachusetts General Hospital, “ER” languished for decades until Spielberg bought the rights “because he heard that I was writing a dinosaur story and he wanted that,” said Crichton wryly.

NBC grudgingly agreed to produce a pilot but the network executives were so convinced of its failure, certain that audiences would never keep up with its fast pace and technical nature, that they turned their backs on Crichton and his co-producer John Wells.

The network’s abandonment was the program’s gift, Crichton said, as it granted them the freedom to create the show exactly as they liked.

Crichton elicited knowing chuckles from his audience as he described coaching actors to become doctors, training them to rattle off lab results instead of treating them like dramatic dialogue.

“Actors are trained to look at faces when they talk,” Chrichton said. “I said ‘no, no, you’re supposed to look at the injury … because that’s what you’re there for, you’re the doctor.’”

His own training as a doctor has served him – and the award-winning series – well by putting him firmly in touch with the true stories that provide the show’s dramatic core. “That, I think, is a legacy of having been trained at an institution like this,” he said.

Medical school also boosted his sense of empathy and caring for people, a rare commodity in “a business primarily marked by selfishness,” he said. His own experience in the ER is represented by the characters of Dr. Greene and Dr. Carter.

There’s a practical element to his medical training, as well. “I was also really able to stand on my feet for a very long time,” said Crichton. “It turns out, if you’re going to direct, that’s one of the most useful talents.”

Media and medicine?

Crichton fielded audience questions about his career change from medicine to entertainment, his habits as a writer, and the power of media to affect science awareness or social health policy. On the latter, he was decidedly downbeat.

“I don’t believe that movies lead the way in major social ideas,” he said, acknowledging that a well-crafted campaign such as the School of Public Health’s designated-driver effort can effectively marshal Hollywood’s might for social message. “I tend to believe that the media is the way to drive the nail the last quarter-inch. It’s not the way you put the nail in the board with the first couple whacks.”