Journalists speak out at Russian conference

Harassed Russian journalists get help from Harvard

Russian journalists struggling to maintain freedom of expression found an influential ally last month – Harvard University.

The Davis Center for Russian Research, the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, and the Nieman Foundation collaborated with several other organizations, both Russian and American, to organize a conference in Moscow Feb. 8-9 on freedom of the press. About 300 people from all parts of Russia attended. They included independent journalists as well as government representatives, including the minister of communications.

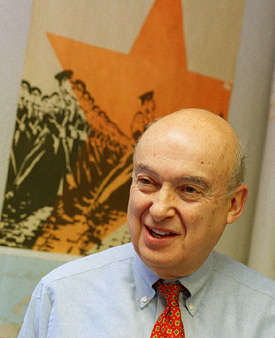

What was notable about the conference was that at a time of bitter conflicts in Russia between journalists and the government, representatives from both groups were able to sit down together and discuss the issues at hand. According to Davis Center Associate Director Marshall Goldman, it was partially Harvard’s participation that made this encounter possible.

“For me, one of the most satisfying comments was made by Boris Jordan [head of the government-supported Gazprom-Media] – that it was only because the Davis Center and Harvard were involved that he and the other people agreed to come and be civil to one another while on the same panel,” Goldman said.

Russian journalism, which enjoyed unprecedented freedom during the 1990s under the leadership of Boris Yeltsin, has suffered a new wave of repression under Vladimir Putin. But instead of the old-style Communist censorship, the new controls come into play through takeovers of media outlets by giant business conglomerates operating with government support.

In 2001, for example, the Russian utility company Gazprom, a substantial portion of which is owned by the government, called in loans it had made to the independent network NTV. The move enabled the government to take over the station. Commentators have accused Putin of manipulating the takeover to end the network’s criticism of the war in Chechnya.

After the takeover, many journalists who had worked for NTV fled to another independent network, TV-6, but this network met the same fate when it was taken over by another utility giant with government connections, Lukoil.

“Putin says he supports freedom of the press,” said Goldman, “but then he accuses the private oligarchs of using the media for their own personal vendettas. He contends that private ownership of the media means that it’s tainted and can’t be trusted. What we were trying to say was that the more diverse the voices, the more the public can trust the media.”

Since the demise of TV-6, many of the harassed journalists went to work for a Moscow radio station called Echo Moskvy. The addition of new talent increased the station’s popularity and the size of its audience, but the day before the conference it was announced that Gazprom-Media had taken over the management of this station as well.

Echo Moskvy continues to broadcast, although a large number of journalists have left the station. The breakaway group subsequently submitted a proposal to take over a new FM station and their offer was accepted. Goldman thinks the conference may have had an impact on this turn of events.

“It’s not clear, but we’d like to think we had some influence there.”

Another Harvard attendee, assistant professor of government Yoshiko Herrera, agreed with Goldman’s assessment.

“The conference turned out to be an expression itself of freedom of expression, probably because Harvard was involved,” she said.

Like Goldman, Herrera felt that the most important aspect of the conference was allowing the antagonists in the media conflict to face each other and to hear each other’s point of view.

“The conference allowed the government people to face their critics, and that in itself was something of an achievement.”

In some cases these meetings had very real results. For example, during the conference the head of Echo Moskvy, Alexei Venediktov, met privately with the Minister of Communications, Mikhail Lesin, and, as a result, the Minister agreed to an on-air interview.

Nieman Foundation curator Robert Giles, who attended the conference, said he was particularly struck by the sessions at which journalists from outlying regions of Russia spoke of their experiences dealing with repression and censorship.

Giles described one session at which journalists spoke in chilling detail about the ways in which local mayors and officials intimidate the press, including physical coercion and even murder. One speaker described how a mayor took over distribution of a local paper to prevent readers from seeing an article he objected to.

Nevertheless, Giles felt that the overall effect of the conference was positive.

“I think it was encouraging that so many people came from all over Russia to discuss these issues in a candid way,” he said.

Giles said that the Nieman Center is prepared to do its part to promote freedom of the press in Russia by collaborating with the Davis and Shorenstein Centers to bring more Russian journalists to Harvard as visiting fellows.