It’s the technology, stupid

The Web sparks enhanced learning

A young psychology concentrator is leading a class discussion on decision-making and emotion, and Christine Soutter, graduate student and teaching fellow for this sophomore tutorial, can’t believe what she’s hearing. Although it’s just a few months into the students’ serious engagement with the subject, their discussion of emotion is at the level of polished graduate students.

From class discussions to writing assignments, Soutter has seen her charges soaring higher than students she’s taught in the previous four years of sophomore tutorials. Her current students, she says, “got a faster, better grasp of this in October than my other classes did in April. They can run a dynamite class because they’re really on top of what’s going on.”

Soutter thinks she knows why her students have such an impressive command of the difficult and unfamiliar material.

It’s the technology, stupid.

Soutter and her colleague Orville Jackson spent this past summer developing a Web site for the psychology sophomore tutorial that would, they hoped, help new concentrators “assimilate more quickly to what the norms are in this new culture they’ve dropped into,” she says. It’s one of many ways that Harvard faculty members are harnessing technology – especially the World Wide Web – to enhance learning.

Putting pedagogy first

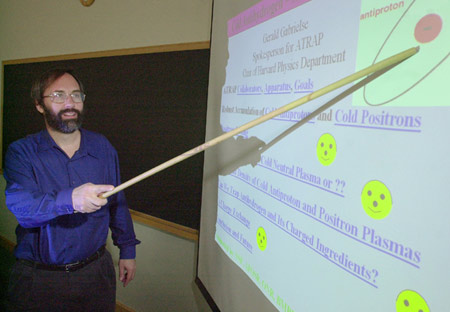

“It’s improving the quality of the education the students are receiving,” says Professor Gerald Gabrielse, chair of the Physics Department, “as long as the technology isn’t the leader but the pedagogy is.”

Gabrielse, a self-described geek who has had his own Web site for 10 years, went beyond the standard Web tools available to all Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) courses through the FAS Instructional Computing Group (ICG). In addition to availing himself of those tools, generating online discussion groups, posting lecture notes on the Web site, e-mailing announcements and assignment reminders, Gabrielse contracted with an outside Web development group to implement a Web-based assignment tool.

Using it, students in his Core course “Reality Physics” entered the results of their homework problems and got immediate feedback. If the answer was wrong, says Gabrielse, they could try repeatedly until they got it right.

His initial concern that students would miss the instructor’s hand-scrawled notes on their work pointing out where they had gone astray was unwarranted. “The students were overwhelmingly enthusiastic. They were more than willing to give that up in exchange for the immediate feedback,” he says, adding that such technology would likely not work well for more advanced courses.

From ‘dry’ to ‘dynamic’

Sylvia Rieger, preceptor in German, strives to maintain her pedagogical footing as she enhances her coursework with Web-based activities, multimedia games, and digital movie clips. “It has to be prepared very carefully,” she says. “A lot of pedagogical thinking has to go into using technology. Just to give them a Web page and two or three questions isn’t enough.”

Students in Rieger’s “German 60: Berlin Since 1989” course made short online documentary videos of conversations with contemporary Berliners, utilizing software developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Overlaying solid teaching techniques atop innovative technology, Rieger says she deepened her students’ understanding of Berlin and their German reading and writing skills. “They got a very personal insight into aspects of living in Berlin. It complemented their outlook on that subject,” she says.

“It has turned the classes much more dynamic,” says José Antonio Mazzotti, assistant professor of Romance Languages and Literature. “Students participate more and in consequence they learn more.” Mazzotti created a Web site that breathed life into his course on Spanish American Colonial literature – “the readings might be perceived as difficult and a little dry,” he admits – with maps, paintings, music, and cultural information.

From syllabus to scroll

Last term, 463 FAS courses activated their ICG-granted Web sites, according to ICG senior manager Paul Bergen. Many of those sites are basic, simply offering electronic delivery and storage of course handouts. While students find such administrative streamlining valuable and in fact rated many such sites highly in the CUE scores, Bergen notes that these sites are hardly breaking new pedagogical ground. (Most FAS classes enrolling 20 or more are evaluated by students each semester; results are tabulated and published by CUE, the Committee on Undergraduate Education.)

“The most innovative uses are those that use the medium of the Web to present materials in ways that would otherwise be impossible,” he says. Science courses can put pre-lab videos on their sites to familiarize students with equipment and procedures in advance, for example. Audio clips enhance music courses immeasurably; the Web site for the Core course “Chamber Music from Mozart to Ravel,” taught by Robert D. Levin, Dwight P. Robinson Jr. Professor of the Humanities, annotates a difficult article on music theory with more than 200 musical examples played by Levin himself.

Bergen’s staff helped another Core course, “The Chinese Literati,” taught by Peter K. Bol, Harvard College Professor and Professor of Chinese History and chair of the East Asian Languages and Civilizations Department, show students a 14-meter scroll painted in early 17th century China.

With only one reproduction available, the scroll is otherwise inaccessible to students. But the online version allows students to carefully study the scroll, weaving together more than 80 scans that the user literally drags across the screen to open the scroll just as one would with the paper original. The professor’s instructive commentary pops up as one scrolls past key points in the illustration.

Ramping up students’ skills

Thanks to a grant from the provost’s office, Christine Soutter and Orville Jackson took advantage of ICG’s expertise to beef up the Web site for the Psychology Department’s sophomore tutorial, creating tools that would streamline students’ comprehension of the methods and terminology of psychology.

A sample research paper with an annotated glossary and sections from the textbook authored by head tutor Stephen M. Kosslyn, John Lindsley Professor of Psychology, and Robin S. Rosenberg, help sophomores ramp up their skills. Hilles Library wrote an online tutorial for PsycInfo, a powerful database copyrighted by the American Psychological Association, that students can access from the site.

Using online discussion groups, Soutter preps her students for the week’s reading or in-class discussions. Students post their papers so that their classmates can read – and learn from – their work.

The site also provides private file cabinets for all students; Soutter makes electronic comments on their weekly papers. “Turnaround is crucial,” she says, so that students can learn from each week’s paper and build on it, and she points to an illness this fall that made her electronic feedback even more important. “The feedback they did get was because I could do it in bed with a laptop,” she says.

Eliot Hamlisch ’04, a psychology concentrator and one of Soutter’s students, gives the tutorial Web site high marks. Reading his peers’ work has been useful to him, he says, and he likes the electronic storage of his own work that lets him review previous papers and comments to produce new work. “It’s a much more interactive and in-depth system we’re using,” he says, adding that his roommate, taking a history tutorial, must print out multiple copies of papers for all classmates.

Enhancing teacher-learner contact

Contrary to what might seem an obvious concern that Internet learning might foster isolation, professors and tutors report that e-mail and Web sites are giving students more, not less contact with their teachers. “They feel more supported,” says Gabrielse. “And if they feel more supported, they’re more likely to come by to office hours.”

What’s more, technology helps connect students with their teachers when they need it most. “Students are getting guidance and support … when they’re at home in their rooms staring at this piece of paper trying to figure out what the heck it says,” says Soutter.

Gabrielse concurs. “Often times, the teachable moments happen when there’s no office hours,” he says.

Both Gabrielse and Soutter say that technology has made face-to-face time with students, whether in class or during office hours, more productive. Gabrielse even notes that the administrative ease of posting class materials on the Web or announcing class business via e-mail frees up time for him to give extra help to students who are struggling. “That’s hard to do if you’re spending a lot of time passing things out,” he says.

Personnel cost

Still, whiz-bang Web sites and midnight e-mails don’t materialize by magic: there’s an undeniable personnel cost to enhanced technology. “It’s an investment,” says Mazzotti, who, along with Rieger, built some efficiency into his Web sites that will make consecutive ones speedier to implement and manage.

Efficiency motivates Bergen and his team at the Instructional Computing Group, which has seen a dramatic increase in the demand for its services. By automating simple Web tasks and discouraging the devotion of too much energy to what Bergen calls “window dressing” – gratuitous flashy graphics and other resources that are unrelated to the teaching of the course – ICG can concentrate on implementing ambitious ideas that enhance learning.

For those who have witnessed interactive technology sparking their students, however, there’s no turning back. “Now that I’ve discovered this technology, this means of making our courses more dynamic, I would recommend this to others,” says Mazzotti.

“There’s something incredibly exciting to a teacher who watches her students come to life in a discipline that they’re just entering,” adds Soutter. “If you can accelerate their arrival at the mastery and sophistication that will satisfy them and delight them, if you have the time, why wouldn’t you want to use it?”