High-tech eludes most nations

Report shows developing countries have a long road ahead

There’s a story told of a poor farmer in a developing country who, when given access to a computer hooked to the Internet, was able to check commodity prices in faraway markets to see how he should price his goods.

The story may be true, said Geoffrey Kirkman, managing director of the Information Technologies Group at the Center for International Development (CID), but it misses the point.

Around the world are isolated examples of ways in which individuals have used technology to their benefit, but for technology to fulfill its promise in leveling the playing field between developing and developed countries, the single extraordinary example has to be multiplied until it is neither single nor extraordinary.

“There is truth in the anecdotes, but they only go so far,” Kirkman said. “There aren’t any widespread success stories.”

Though many are eager to extend the information revolution into developing countries, the truth is that governments, businesses, international organizations, and development agencies don’t really know the best way to do it, Kirkman said. This uncertainty can lead to well-intentioned but ultimately wasted efforts as projects are launched and equipment donated that doesn’t meet local needs.

“Greater attention needs to be paid to these issues because we don’t understand them yet, and so scarce resources aren’t wasted,” Kirkman said.

In an effort to enhance understanding of the situation, the CID, in collaboration with the World Economic Forum, released a 402-page report in early February called the “Global Information Technology Report 2001-2002: Readiness for the Networked World.” The report assesses the readiness of nations around the world to take advantage of information and communication technologies.

The United States is at the top of the report’s “Networked Readiness Index,” which ranks 75 countries according to their ability to take advantage of opportunities presented by the new information and communication technologies. After the U.S. comes Iceland, Finland, Sweden, and Norway, with Japan 21st, France 24th, and Russia 61st . Last is Nigeria, with Vietnam, Bangladesh, Honduras, and Ecuador filling out the lowest five in the rankings.

“The networked world is here to stay, but the changes have happened so fast that we don’t really understand our new surroundings,” Kirkman said in the report’s executive summary. “ICTs [information and communication technologies] have yet to be adopted or used by most of the world, but it is those people who have not yet used the Internet or spoken on a telephone who perhaps have the most to gain from the potential of ICTs.”

The report, aimed at policymakers, businessmen, and workers in international nonprofit organizations, provides two-page “snapshots” of the readiness of each of the 75 countries featured in the report. In addition, it includes a series of discussions by experts on related topics, such as “Community Internet Access in Rural Areas,” “Leveling the Playing Field for Businesses in Developing Nations,” and “Rethinking Learning in the Digital Age.”

Despite the data presented in the report, Kirkman said its most important conclusion is that more work needs to be done.

“The most important message of the report is that we’re at the beginning of trying to understand how information technology impacts economic development,” Kirkman said. “We need to push our understanding. We’re still only at the beginning.”

One way the CID is trying to push the world’s understanding of this issue, Kirkman said, is with pilot projects around the globe that explore different ways technology can be tailored so it is useful at the local level.

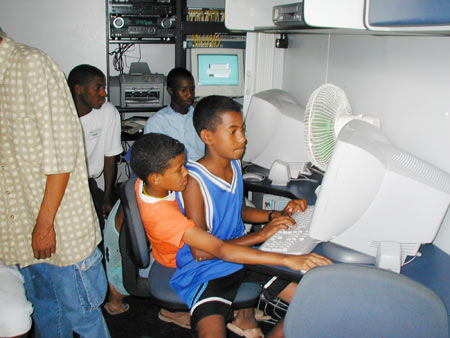

In the Dominican Republic, CID is interviewing key public, private, and nonprofit officials to prepare an in-depth report on the nation’s readiness for the networked world. In addition to the report, the CID is convening a series of public/private roundtables to bring major actors in the country’s economy together. The process will result in planning for specific projects that would incorporate information and communication technology in key areas, such as schools, universities, community computing centers, and small and midsize businesses.

In one project, in Tamil Nadu in India, the CID is working with local agencies to complete 1,000 Internet connections in 350 villages, and develop ways to use the access to benefit the area residents.

Kirkman said one of the project’s first steps is the development of new computer technologies that result in inexpensive, stripped-down machines that will not only be affordable, but also functional in the rural settings. The project, called Sustainable Access in Rural India, is being undertaken with three partners, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, IIT-Madras, and the I-Gyan Foundation.

“The technology is highly promising in unexpected ways, often,” said CID Director Jeffrey Sachs.

Rather than having to invest millions of dollars and years of effort to run telephone and power lines to poor areas, users in rural areas can use wireless phones for communications and for connection to the Internet.

Not only can farmers and merchants use new information to figure out where and when to sell their crops and products, poor rural residents can gain access to online government services and documents, such as birth certificates, sparing them exhausting trips to provincial capitals in order to negotiate confusing bureaucratic mazes. In addition, rural health centers can make referrals to larger hospitals, provide information on epidemics and outbreaks, and even get advice on medical care.

“We’re of the view that this kind of access to government functions can be of tremendous use to poor countries,” Sachs said.

Unfortunately, however, the rising promise of technology is often not the only agent at work in these countries, Sachs said. Hand-in-hand with the promise of technology are the everyday dangers of poverty, government instability, inadequate health care and nutrition, and environmental degradation.

“So much of this is a race against time. There’s so many adverse things going on in developing countries – disease, population stress, environmental degradation, stress on water supplies,” Sachs said. “Without help from the international community, for a significant number of countries and several hundred million people, the adverse forces are going to overwhelm the positive forces.”

Portions of the report are available on the Web at http://www.cid.harvard.edu/cr/gitrr_030202.html.