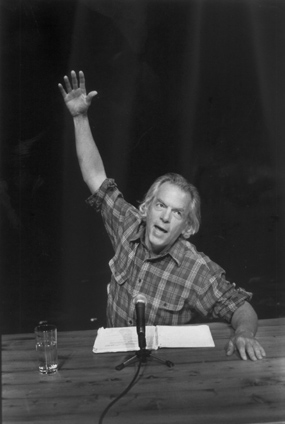

Spalding Gray tells all!

Monologist talks of recent triumphs, pain

Spalding Gray may best be known for ruthlessly blurring the line between life and art. Since 1979, he has been writing and performing confessional autobiographical monologues that plumb life’s experiences for all their irony, absurdity, and edgy intensity. He’s been compared to Anna Devere Smith, Garrison Keillor, and Anna Quindlen and called a “new wave Mark Twain.” Since founding and fronting the boldly experimental media and theater ensemble, the Wooster Group in lower Manhattan, he has toured with his work and appeared in feature films. The making of Roland Joffe’s “The Killing Fields” (1984) inspired “Swimming to Cambodia,” a monologue that Gray first performed in 1982 and made into a film in 1988. He is reviving it at Sanders Theatre this weekend.

Much of Gray’s comic work is born of grave distress. His memoir (and monologue) “Gray’s Anatomy” (Random House, 1994), for instance, was based on his global pursuit of a cure for his rare eye disease. On June 22 last year, he again ran into the chaos he aims to sort out in his monologues when a van smashed into his car on a country road in Ireland, cracking his skull. He continues to suffer from damage to his sciatic nerve. He has a dropfoot (paralysis of certain leg muscles) requiring an orthotic brace. The incident spawned an intensive physical therapy regimen as well as an ongoing bout with depression. Last Wednesday, he spoke to the Gazette from his Long Island home about this and other calamities. His trademark chattiness and vigor were a bit muted, but his searing honesty and insight were blasting full volume.

Question: Why are you reviving “Swimming to Cambodia” now?

Answer: “Now” was really set up a year ago. It was a request from U.C.L.A. They said “could you bring something old back?” because I didn’t have any new work that I was working on then and didn’t see anything coming on. I had to choose a monologue and that was a classic — and a good one.

Q: Do you see it as having tie-ins to Sept. 11, seeing that Cambodia was a country Americans hadn’t paid much attention — and some of the circumstances are similar to Afghanistan?

A: Right. It has those ramifications in it but it was booked way before 9/11. It certainly has a lot of reverb, a lot of echoes in it, but it’s kind of inverted in a way. We were invaded. In this [Cambodia’s] case, we weren’t. We invaded. We lived it. We’re the bad guys.

Q: You have status as an iconic New Yorker on a par with, say, Woody Allen, Jerry Seinfeld. Like them, you feed off the anxiety of the city (despite your move to Long Island). Though you’ve said New York is a city that defies observation, what observations have you logged since the cataclysmic events?

A: That’s a lot of the depression that I’m going through: that I wasn’t there for it. I was out here on crutches so I didn’t go in to Ground Zero until quite late. Observations that I logged were, um, very similar to any latecomer coming into that situation. The city was — at least downtown — very much slugged-out and grieving. With all the signs and candles up, you couldn’t avoid looking around and seeing signs of lost ones. … How has it affected me? It’s hard to say this, but my disaster came when I was hit by a van — that shook me up so badly — and also we were moving on the day of 9/11 [to just outside Sag Harbor]. Then I went to perform at Wesleyan, so I never got [to Ground Zero] when I wanted to. When I went to Ground Zero and walked around later … a policeman took me around. I was there watching them spray down the endless fire. I wasn’t a quintessential New Yorker [on 9/11]. I’d been living [on Long Island] for five years and coming into the city just once a week. I’ve barely taken it in because I’m so caught up with my own injury at this point.

Q: A lot of your best-known works have developed from your trips to far-off countries, ones that some may even consider exotic — Cambodia, the Philippines … Sag Harbor — for very explicit purposes. Any thoughts about projects that might involve a trip to Afghanistan?

A: No.

Q: You write [in the author’s note to “Swimming”] “I am interested in what happens to the so-called facts after they have passed through performance and registered on my memory.” Can you talk about making a film of a work so grounded in its live performance?

A: Boy, that was a watershed film, a breakthrough, because [director] Jonathan Demme was interested in sticking to a talking head. No one had ever done that before. They always wanted to do a lot of cut-aways. In that way the film was important. Now it bugs me — not that it exists — but I feel like I’m competing with it by doing the live event. When I performed it at the [Wooster Group’s] Performing Garage, I asked people afterwards what they got out of it. They said the live performance was different for them. What grabbed them was that it was extremely intimate, just me telling the story to these hundred people. That’s what they said worked. For me, making the film was a way of casting off a snakeskin: farewell to it. That’s the record of it.

Q: Like a catharsis?

A: More so than [writing] the book because the movie was an image, and you’re closer to live performance.

Q: You’ve worked with a number of powerhouse Hollywood directors, from Ron Howard to John Boorman to Steven Soderberg to Jonathan Demme. Did you ever have any concern submitting to the ones who directed your own monologues?

A: No, Jonathan in particular stayed close to the text and Steven was a little more experimental [with “Gray’s Anatomy” (1996)]. But I was open to it. He built sets and had it more theatricalized. With Boorman, that was his text [“Beyond Rangoon” (1995)] I always like to work on films as a break from my own work, and be told what to do. I often worry directors don’t want to cast me because they think I’m going to want too much a hand in creating a film that’s not mine. I’m actually very passive and directable in someone else’s film, and I try to be when I’m doing my own work.

Q: New York Times critic Mel Gussow called you a writer, reporter, comic, and playwright. I’m going to add actor to that catalogue. Can you arrange those in order of importance to you?

A: Is author in there? Writing and the performing go hand-in-hand. They’re the important ones because I’m creating the piece in front of the audience, I’m making the sentences, they’re not [always] pre-written. There are the keywords and then I speak it, so it’s a form of oral writing. It’s definitely an oral composition, storytelling in the Irish sense of first-person present talking about your own life. I suppose acting is probably at the bottom of the list. Although I do act, when I perform I’m acting myself. [Then] I’d say humorist. Or humanistic humorist reporter.

Q: As you’ve noted on several occasions, humor comes out of an enormous pain.

A: Often.

Q: Is your work a means of therapy for you?

A: To some degree.

Q: There is a theme of balance that steadily runs through your work. From finding the balance between mind and body while skiing in “It’s a Slippery Slope” [1996; recording, 1998] to finding balance in your life and work while raising children on Long Island in “Morning, Noon, and Night.” [1999] In “Gray’s Anatomy” you realize a “perfect yin-and-yang existence.” It all resounds with a Zen-like sensibility. How much of this is a reflection of your religious beliefs?

A: Um, I don’t know if I can answer that. Right now I’m so unbalanced in my body that I can’t celebrate that notion. It’s hard for me to speak because I’m in a state of despair now. I think the monologue is always seeking to at least express the balance in a story, if not in real life. It usually reflects falling apart and coming together again.

Q: You’ve likened it to “Humpty Dumpty” before.

A: Yes, I’ve often thought of “Humpty Dumpty” or “All the King’s Men” as names for all the monologues, but they have already been used. That and “Terrors of Pleasure” — the terrors of dealing with pleasures and pain. As titles, those could apply to all of them. Right now I’m just having trouble adjusting to this dropped foot so I don’t feel whole yet. I’m hoping the nerve will restore itself, through PT and some acupuncture. But I’m glad you see that in the monologues.

Q: You’ve said you were influenced by works by Herbert Marcuse and Norman O. Brown. I’ve also read that you went on a Raymond Carver kick. What are you reading these days for creative sway?

A: I’ve barely read since the accident. The only thing I read last night was an article in The New York Times science section about black matter. Interesting. In the hospital in Ireland, I was so completely filled up by [Jonathan Franzen’s novel] “The Corrections.” I was very completed by that book. I cried when I closed it.

Q: Would you talk about your accident?

A: [It happened] June 22 in Ireland. God, I don’t remember the territory. Just northeast of Dublin, dairy country. We were five adults in the car stopped to turn right on this very narrow road and this guy came around the corner in a van. He hit us. I was in the back seat and [my partner] Kathie was driving. I flew forward, impacting my head on hers. Her seat came back. The engine went right into the cabin. I think what happened was the seat pushed my femur, dislocated my hip and fractured my [skull]. Next thing I know I was in a puddle of blood on the road. It was an hour before the ambulance came. It changed my life, the accident. Everything was fine and then five seconds later, I was lying in a puddle of blood.

Q: What was it like to be in a hospital so far away?

A: There are a lot of absurd stories that came out of it. I actually open “Swimming to Cambodia” with it as a lead-in as to where I’m coming from.

Q: In the days of the Wooster [Group’s Performing] Garage’s intimate, bohemian settings, did you ever have any idea that you’d be where you are today?

A: No, no the future has always been a surprise to me. I was very lucky to find this way of working.

Gray’s reprise performance of “Swimming to Cambodia” is at Sander’s Theatre tonight, Thursday, Jan. 17-Saturday, Jan. 19. For ticket information call (617) 496-2222