Reading ancient textiles

Fragile cloth artifacts yield enduring information

Hidden away in the storerooms of the Peabody Museum are nearly 5,000 ancient Peruvian textile pieces, perhaps the largest such collection outside Lima.

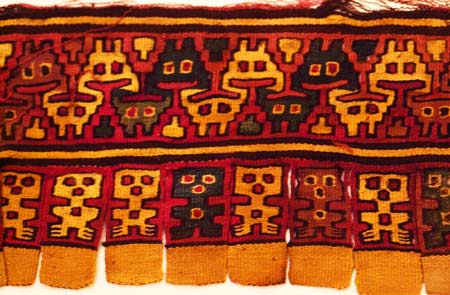

They range from 4,000-year-old nets made from knotted cotton cord to more recent tapestry fragments woven from alpaca and other native wools showing colorful bird and animal motifs. The crown of the collection is a group of intact cloaks – large squares of cloth with carefully executed details in tapestry or embroidery, including one exquisite example woven from vicuña, the softest and rarest type of Andean fabric.

There is an abundance of information to be gathered from these fragile cloth artifacts, but it takes an expert to tease out their secrets, to discern the twist of the thread, the microscopic profile of the fiber, or the peculiarities of warp and weft, and from these reconstruct the technological and even the social conditions under which the specimen was produced.

Irene Good is such an expert, and with her one-year appointment as the Hrdy Visiting Curator in Anthropology, the Peabody’s Peruvian textile collection is finally getting the attention it deserves.

Getting her hands (carefully gloved, of course) on such a collection is a high point for Good, whose fascination with textiles goes back to early childhood. Most textile remains are far less well-preserved, and this makes studying the Peruvian collection a rare privilege for someone with Good’s level of expertise.

“Working with a whole garment is a real treat for me. I’m used to looking at tiny pieces and holding my breath so they don’t disintegrate.”

Good’s painstaking analysis of these artifacts will provide important data about the Incan civilization from which they came. Just as pottery fragments provide archaeologists with evidence by which to date events or chart the movements of people or the flow of goods and ideas, textiles furnish their own set of clues, which shed light on such things as agriculture, animal husbandry, trade, and technology.

The difference, of course, is that ceramics are far more durable, but specialists like Good have devised ways of gleaning valuable data from textile fragments that were once thought hopeless.

Good plans to publish her study of the Peruvian textiles as a book, illustrated with color photos of some of the collection’s extraordinary pieces. The book should help to bring the collection to the attention of scholars as well as the general public. It should also help to focus attention on textile study as a valuable archaeological tool, a result that Peabody Director Rubie Watson believes would be well worthwhile.

“We are very pleased to have Dr. Good at the Peabody,” Watson said. “Her work will highlight this important collection and the research value of textiles in general. The study of early textiles, which combines technical and cultural analysis, is a very exciting new field within archaeology.”

As a pioneer in this new field, Good is on the forefront of textile research, but she arrived there not so much out of a desire to stake out unoccupied territory but by simply doing what she loved.

As a young girl, Good learned to crochet from her grandmother, and practicing this newly acquired skill prompted her to wonder about the universality of textile production.

“I remember thinking, isn’t it amazing that we can weave, and that everyone in the world somehow figured it out.”

Not long afterward her parents bought her a loom, and she branched out into spinning and hand weaving. At around the same time, she got her first taste of field archaeology when she signed on as a volunteer at an excavation of a woodland Indian site near her home on Long Island. As a result of that experience she decided to become an archaeologist.

In graduate school, Good gravitated toward the more scientific aspects of the field, learning to use a scanning electron microscope to study buried pollen and spores as a way of tracing changes in the environment. One day, a fellow archaeologist brought her a fragment of burned cloth he had excavated and asked if she could tell him anything about it.

“I realized at that point that my backgrounds in weaving and microscopy had merged.”

Since then, Good has continued to push back the boundaries of textile research, developing techniques for extracting information from degraded fabric specimens that in former years would have been disregarded by even the most thorough of excavators.

Her work has taken her to China, central Asia, India, and Eastern and Western Europe, drawn at times by a few wisps of silk or wool that hold the key to some mystery of cultural exchange or migration.

In Prague, for example, she examined an Egyptian mummy purported to have some silk threads in its hair. In Stuttgart, she looked at silk threads from a 700 B.C.E. burial mound excavated in central Germany in the 1930s. The presence of what was believed to be Chinese silk had been cited as evidence of trade routes stretching from China to Western Europe, but Good was skeptical.

By examining the amino acid composition of the silk, Good was able to determine that it came not from domesticated Chinese silkworms, Bombyx mori, but from a wild Mediterranean variety, Pachypasa otus. The silk had not come from China, after all. But Good’s research did provide new evidence for an early European silk industry whose existence had not been well documented.

In her work with the Peabody’s Peruvian collection, Good hopes to make new discoveries, which will perhaps lead to new insights about the interaction of the highland and lowland peoples of the pre-Columbian Andean world.

Her day-to-day work, often involving detailed, repetitive tasks like counting threads in a weave or analyzing the complex technique used in a piece of embroidery, may at times seem tedious, much like the work of the ancient people who produced these artifacts. But as Good’s career has already shown, out of such careful and meticulous analysis can come major insights.

“I’m often surprised how little people in archaeology are aware of how informative archaeological textiles can be,” she said. “I hope my work can help us better understand what can be gleaned from them.”

Contact Ken Gewertz at ken_gewertz@harvard.edu