“The Ethical Foundations of Dr. King’s Political Action”

Remarks of Charles V. Willie

Charles William Eliot Professor of Education, Emeritus

On the occasion of Martin Luther King Jr. Day

January 21, 2002

The Memorial Church

Harvard University

As prepared for delivery

Gabriel Vahanian has written a book titled “Wait Without Idols.” The title of that book bears a message for us as we celebrate the birth and life of Martin Luther King Jr. We should be careful not to idolize him, not to dehumanize him, not to describe him as if he were a magician.

It is an ancient custom, as ancient as the Roman Empire, to idolize those whom we honor, to make them larger than life, to give their marvelous accomplishments a magical and mystical origin. By exalting the accomplishments of Martin Luther King Jr. into a legendary tale that is annually told, we fail to recognize his humanity — his personal and public struggles — that are similar to yours and mine. By idolizing those whom we honor, we fail to realize that we could go and do likewise. As I have said on many occasions, honoring Martin Luther King Jr. would be dishonorable if we remember the man and forget his mission. For those among us who believe in him, his work now must become our own.

This discussion is different from most about Martin Luther King Jr. It focuses on his mission for world peace rather than on his contribution to the civil rights movement. We should remember, however, that local movements and international missions are interconnected. Martin Luther King Jr. understood this. But many of his foes and some of his friends did not.

Early days

Let us meditate for a moment on his early days and the context from which he emerged. The college that he attended was a significant experience that conditioned his concern about justice.

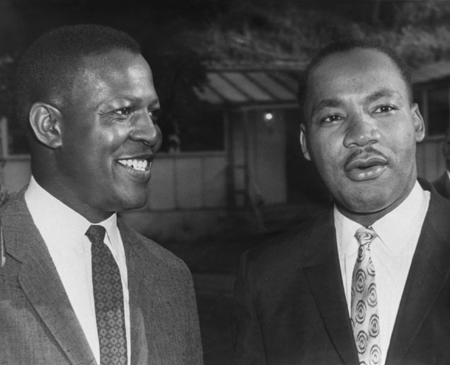

Samuel DuBois Cook, president of Dillard University in New Orleans and a classmate of Martin Luther King Jr., came to Cambridge, Mass., during the Bicentennial year to participate in a conference on black colleges that I organized at Harvard. Dr. Cook left these words resounding in the hallowed halls of that great institution. He said, Martin Luther King Jr. had to come out of Morehouse College rather than Harvard College.

This statement was not intended as a put-down of Harvard College or any other school; but it surely did uplift Morehouse College. Morehouse College taught Martin Luther King Jr. that justice is love in action (as stated by Joseph Fletcher). Morehouse College taught Martin Luther King Jr. that justice is fairness (as stated by John Rawls). For Martin Luther King Jr., Morehouse was to Harvard what the manger was to a room in the inn for Jesus — a humble and lowly beginning.

The imagery is powerful and something to think about. It is good to remember, that which is good may be humble and that which is lowly may be good. Even within the context of an educational institution, we must be careful not to judge the brightest as always the best.

The influence of war

The issue of war and peace influenced the course of Martin Luther King Jr.’s life early on.

Morehouse is a predominantly black, liberal arts, men’s college in Atlanta. Students were being drafted in large numbers in the early 1940s for World War II. To remain a viable institution in this crisis, Morehouse College decided to take into the freshman class students who had finished only the 11th grade. In September 1944, 15-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. became a freshman college student. (As a footnote to history, I too was a member of that class.)

King’s early admission to college, then, was associated with the evil of war. Martin Luther King Jr. called Benjamin Elijah Mays, president of Morehouse College, his spiritual mentor. From him and others emerged King’s commitment to love, justice and peace.

The words and works of King for peace

In the last sermon that Martin Luther King Jr. preached at Ebenezer Baptist Church, he said: “Every now and then I guess we all think realistically about that day when we will be victimized with … death …. If you get somebody to deliver the eulogy, tell him not to talk too long …. Tell him not to mention that I have a Nobel Peace Prize — that isn’t important …. I’d like somebody to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life serving others …. Yes, if you want to, say that I was a drum major. Say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace.”

This is what King had to say about war and peace: “We are merely marking time in the civil rights movement if we do not take a stand against the war.” Then he said, “You can’t have peace without justice, and you can’t have justice without peace.”

King reminded his fellow citizens that he had preached nonviolence in the civil rights movement in the United States. Then he said, “It is very consistent for me to follow a nonviolent approach in international affairs.” He believed it was important to stand up against war out of moral commitment to dignity and the worth of human personality. War, of course, is evil and King believed that those who ignore evil become an accomplice to it.

Words and works

King not only was a preacher capable of presenting the word; he also was a prophet who revealed the word in his courageous works. He was the word made flesh. He knew that attitudes about peace and justice must coexist with actions to achieve these. He said, “We must pray earnestly for peace, but we must work vigorously for disarmament.” He told us that “the Bible portrays God, not as an omnipotent czar who makes all decisions for his subjects.” “Always,” said King, “[people] must do something.”

And what did he want America to do? First he wanted his country to be humble — not just to say “in God we Trust,” but to act as if we trusted in God rather than in our own firepower and in our own might. A nation that trusts in God is humble and not haughty.

In some churches, the ministers dismiss their congregations from worship services with these words: “Unto God’s gracious mercy and protection we commit ourselves.” Then the members go out into the world and spend a substantial portion of their nation’s gross national product on armaments for protection. We really do not trust in God’s protection, but in our own power. King often quoted historian Charles Beard, who said, “Whom the gods would destroy they must first make mad with power.” I need not remind you that power-madness is forever with us and has been expressed in the recent history of this nation.

King wanted America to cease its warring ways. He admonished us never to seek to defeat or humiliate the enemy. We should seek to win the enemy’s friendship and understanding. This is a marvelous formula for domestic and international relations. Why should we love our enemies? The reason is obvious. King said, “Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars.” Then he suggested the value of asymmetrical action: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” Light and love are asymmetrical to darkness and hate.

Theologian Herbert Richardson stated the admonition about love of enemy in propositional form. Professor Richardson, who called Martin Luther King Jr. “the most important theologian of our times,” said that “in order to overcome … evil, faith does not attack the [people] who do evil, but the structure of evil which makes [people] act violently. Hence, there must be an asymmetry between the form in which evil manifests itself and the form of our opposition to evil. We should meet violence with nonviolence,” said Richardson.

In common, everyday language, Martin Luther King Jr. stated the principle of asymmetry this way: We must meet physical force with soul force. He was so effective in implementing the principle of asymmetry that A. Phillip Randolph called King “the philosopher of the nonviolent system of behavior.”

There is talk among some people about whether King’s message has meaning only for blacks or is relevant for the whole nation. I declare before God in behalf of the citizens of this nation that Martin Luther King Jr. belongs to all of us. And if he belongs to all of us, we all ought to pay attention to his message, especially his assertion that violence cannot overcome violence. I call upon President George W. Bush to recognize the reality of this message and to cease our warring ways around the world.

In Virginia in 1965, King said in a speech: “We won’t defeat communism by guns and bombs and gases. We will do it by making democracy work”; when King suggested the asymmetrical response of nonviolent resistance to the violent aggression of other nations, when he suggested the asymmetrical action of defeating communism by making democracy work, he reaped a whirlwind.

What King believed, he acted upon. The world is full of people who know what is right but who do not have the courage to do what is right. King had beliefs and he acted upon his beliefs. Benjamin Mays, King’s spiritual mentor, said that if you do not act upon what you believe, you do not have a belief at all; you merely have an opinion. Many of us are saturated and even supersaturated with opinions. But these are not our beliefs; and we do not have the courage to act.

In what has been called one of his best speeches, King spoke out April 4, 1967, against war and particularly the Vietnam War. King was an active member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which was against war. He participated as a march leader in the 1967 Spring Mobilization for Peace that brought together more than 100,000 people. He advised young men to consider registering as conscientious objectors. He called for a ban on the testing of nuclear devices. He supported disarmament. He urged our government to endorse the seating of mainland China in the United Nations. He constantly talked about the evil triplets of racism, materialism and militarism.

While the Vietnam War was in progress, King talked about the destructive outcome of meeting violence with violence: “The bombs in Vietnam explode at home,” he said, “they destroy the hopes of possibilities for a decent America … The security we profess to seek in foreign adventures we will lose in our decaying cities.” Meeting violence with violence, in King’s opinion, was a way of achieving a double defeat, defeat at home and defeat abroad.

At times, there was indecision by King as to whether he should oppose war vigorously. He said that he was not a doctrinaire pacifist, that he was not free from the moral dilemmas that the Christian non-pacifist confronts.

Eventually, King made up his mind. He said in his last book that he had come to see the need for the method of nonviolence in international relations. Before achieving this insight, he thought that war could serve as a negative good by preventing the spread and growth of an evil force. But “I now believe,” he said, that “the potential destructiveness of modern weapons totally rules out the possibility of a war ever again achieving a negative good. If we assume that [humanity] has a right to survive, then we must find an alternative to war and destruction. In our day of space vehicles and guided ballistic missiles, the choice is either nonviolence or nonexistence.” For these forthright words, spoken before superpower leaders had the wisdom to reduce nuclear armaments and for uniting his attitudes with action, King was denounced.

The consequence of the peace mission for King

First, King’s popularity slipped, after he denounced the war. At one time he was listed by the Gallup Poll as one of the 10 most admired people in the United States. After his Riverside Church anti-war speech, he no longer was admired.

Writer John A. Williams said, “The closer a black man comes to the truth of America in his writing and speaking, the more quickly, the more positively does the nation’s press close the doors against him.” And so it did against King.

For his courageous actions against war, high political officials turned against him. Let me call the roll. Carl Rowan said that after the Riverside Church speech, King became persona non grata to Lyndon Johnson at the White House. Ralph Bunche of the United Nations disagreed with King. Bunche said King had overstepped his domain. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell proclaimed that “the day of Martin Luther King has come to an end.” Powell ridiculed and disparaged King, calling him Martin Loser King.

King’s friends in the civil rights movement also criticized him, including Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Whitney Young and Norman Thomas “all pleaded in vain with King not to wade into the Vietnam controversy.” Jackie Robinson publicly disagreed with King’s position on Vietnam. These criticisms were described as harsh.

Finally, King’s wife tells us that even his family was uncertain of the wisdom of Martin’s opposition to the Vietnam War. “At first,” she said, “Daddy King did not approve of Martin’s stand.” Eventually King’s father came to believe that not he, but his son, was right. When he came to this understanding, Daddy King described Martin Luther King Jr. as “a genius,” but he claimed no responsibility for assisting him in coming to a commitment against war.

Amid all the opposition from friend and foe, King’s college president and spiritual mentor, Benjamin Elijah Mays, was steadfast in support of his student. Mays said, “I do not agree with the leaders who criticized Dr. King on the ground that he should stick to civil rights and not mix civil rights with foreign policy ….” “I learned long ago,” said Mays, “that there are no infallible experts on war.” Why then, he asked, should Dr. King confine his work to civil rights and leave Vietnam to the government and military professionals.

I tell you about the opposition to King’s opposition to war by his family, friends and others not to blame or defame. Many changed their original opposition to King’s decision against war as the verdict of history came in but were unable to record the change as public information. Moreover, in the middle of confusion and chaos, it was difficult to sort out right from wrong as we strained to see reality through a glass darkly. Who could say now which side we would have been on then?

On suffering and hope

I tell you about these criticisms to warn you that this is one of the possible consequences for people of faith who are steadfast in their attempt to fulfill the purpose of God. I am convinced that from time to time the wisdom of God raises up among us from the most unusual sources archetypal models of leadership for the attainment of justice. And may I say this day that the revelations of mistakes and the allegations of misdeeds will not besmirch the reputation of Martin Luther King Jr., a modern-day suffering servant, and a prophet of the 20th century.

In Biblical days, we had Moses, a magnificent liberation leader, who also allegedly killed one of Pharaoh’s overseers who was abusing a Jewish slave. While Moses never made it to the Promised Land, he led the people of Israel out of captivity and bondage and forever will be remembered for this marvelous deed. And so will Martin Luther King Jr. be forever remembered as a 20th-century liberation leader. His place in history is secure because he laid down his life for the sake of others, an action that many of King’s contemporary critics have not the courage to do.

Hear these words of Martin Luther King Jr.; they are a fitting end to this oration:

I have been imprisoned …. My home has been bombed …. I have been battered by the storms of persecution …. I have attempted to see my personal ordeals as an opportunity to transfigure myself and heal the people involved …. I have lived … with the conviction that unearned suffering is redemptive …. I have felt the power of God transforming the fatigue of despair into the buoyancy of hope …. We face a world crisis …. But every crisis has both its dangers and its opportunities. In a … confused world the Kingdom of God may yet reign.

Suffering, sacrifice and service: this is the legacy that King left for us. This is the way to redemption. This is the requirement for reconciliation. Thanks be to God for sending Martin Luther King Jr. to live and dwell among us. May his soul rest in peace and may we be renewed to fulfill his mission. Amen. Amen.