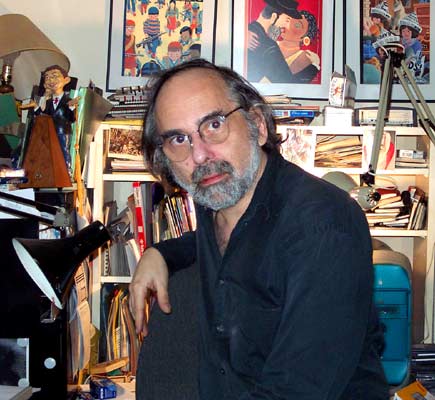

Spiegelman speaks at Carpenter

Comic books have come a long way.

Once considered the lowest form of literature, denounced by parents, teachers, and clergy for their corrupting influence on the minds and morals of youth, comics now command the attention of cultural critics and scholars of art history.

Displayed in shops with names like Tokyo Kid and Million-Year Picnic rather than on wire racks at the local candy store, their subject matter has widened as well. True, Superman, Batman, Spiderman, and other leotard-wearing enemies of evil still retain a substantial readership, but today’s comic book artists are also inspired by subjects like loneliness and alienation, the stories of Franz Kafka, and the plight of the Palestinians.

In this comic renaissance, one name stands out. One artist takes precedence as the creator of a novel in pictures whose innovative approach and fearless handling of painful and complex subject matter puts it in a class by itself. A true crossover artist, his work is as likely to be discussed by college professors as it is by comic book aficionados.

The name of this artist is Art Spiegelman, and the work he has created is “Maus,” a retelling of his father’s experiences during the Holocaust as a sort of animal fable, with the Jews represented by mice and the Nazis by cats. The book won the 1992 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

On Thursday, Dec. 6, Spiegelman spoke at the Carpenter Center. His talk, titled “COMIX 101: Some Notes on the History and Evolution of Comic Art,” was jointly sponsored by the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies and the Committee on Degrees in Literature.

Spiegelman is married to Françoise Mouly, art director of the New Yorker. His black-on-black image of the World Trade Center towers, rendered on extremely short notice for the magazine’s post-Sept. 11 cover, has now become almost as well-known as “Maus.” Spiegelman began his talk with a discussion of how he came to create the cover in the wake of the horrific events of Sept. 11.

“I feel like I channeled the image rather than drew it,” he said.

Spiegelman, who is the father of a young son and daughter, showed slides of other New Yorker covers he has done on the general theme of children under threat. In one, a group of kindergarten children are making doll cutouts and paper hats from newspaper. The still visible headlines say things like “terrorist bombings” and “drugs.”

On another famously controversial cover, Spiegelman sought to help bring together the factions involved in violence between African Americans and Orthodox Jews in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn by showing an Orthodox Jewish man kissing an African-American woman.

“It worked,” he said. “They united in both getting very angry at me.”

But Spiegelman made the point that his critics were only seeing in the drawing what their experiences disposed them to see. “It’s the situation that’s hot, not the image.”

A notable instance of readers finding private meanings in the image of the brown-skinned woman and the bearded, black-garbed man occurred when one girl wrote to applaud the magazine for celebrating Lincoln’s birthday by showing the signer of the Emancipation Proclamation kissing a slave.

Far from being saddened by these misinterpretations, Spiegelman said he was happy that pictures still have the power to shock. He remarked that cartoons, with their simplified, compacted images, are able to pass beneath the reader’s critical radar and deliver their meanings with an immediacy that other art forms cannot match.

Spiegelman traced the history of comics from their “grandfather,” William Hogarth, 18th century creator of moralistic graphic narratives such as “The Rake’s Progress” and “The Stages of Cruelty,” to early 20th century pioneers like Richard F. Outcault, creator of “The Yellow Kid,” and Windsor McKay, creator of “Little Nemo.”

There was a lot of material to cover as Spiegelman galloped through the decades, commenting on slide after slide. Among those he singled out as his favorites were “Krazy Kat” by George Herriman, “a pure cartoonist,” who created “a metaphor so open-ended that it wasn’t a metaphor for anything”; “Dick Tracy” by Chester Gould, a comic strip which embodied “the energy and vulgarity of the tabloid press”; and “Little Orphan Annie” by Harold Gray, whose main character’s empty eyes gave Spiegelman the idea for portraying his Jewish Holocaust victims as human bodies with mouse heads.

Spiegelman called “Peanuts” by George Schultz “the last great comic strip invention,” a strip that has been “widely imitated by lesser talents.” Spiegelman described his meeting with Schultz during which he “fell in love with” the older artist. Spiegelman later published an affectionate parody of Schultz’s work, and Schultz called on the day he died to say that he liked it.

Another cartoonist whom Spiegelman singled out for special praise was Harvey Kurtzman, creator of Mad Magazine, “the only comic to survive because it took on television.” Mad initiated “the age of irony” by telling readers that “everyone’s lying to you,” a message that encouraged baby boomers to question the Vietnam War.

Taking their cue from Mad, Spiegelman’s generation of artists created the underground “comix” of the 1960s, typified by Raw, a publication Spiegelman and his wife edited. These publications made little money and so became “comix for comix’s sake,” breaking taboos against both controversial subject matter and artistic innovation.

Spiegelman and Mouly are now engaged in creating a comic book series for children, a genre that he said has virtually disappeared except for bland productions like “Archie.” Spiegelman plans to engage the best artists and illustrators for the project and hopes to make an impact on children’s literacy.

“A lot of kids have learned to read from comics, and they can still be important in structuring thought,” he said.