The zebra in the freezer

MCZ’s Chupasko prepares specimens for mammal collection

A pygmy hippo has died at the Franklin Park Zoo and Judy Chupasko is troubled. Not because of its death: all indications are that the 33-year-old male died of natural causes.

Rather, Chupasko, curatorial associate at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), is fretting because her freezer is full. “I can’t let them throw it out, but I don’t know what to do with it. I still have part of the zebra in my freezer,” she says. There’s no way she can shoehorn 700 pounds of pygmy hippo – “an oxymoron,” she says – into cold storage.

Trained as a zoologist, Chupasko collects and prepares specimens for the mammal collection at the MCZ. Although she has an office at the museum, she works two days a week deep in a former artillery bunker at the MCZ’s Concord Field Station in Bedford. “This is the fun part,” she says of her hands-on work at the Field Station.

The specimens Chupasko prepares – from shrews to whales – are added to the museum’s mammal research collection, which numbers around 80,000. “It’s a pretty good-sized university collection,” she says, noting that there are only about 4,000 species of mammals in the world. “The one reason why our collection is really valuable is that it’s very old and therefore historical in scope.”

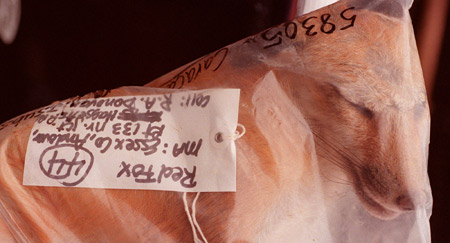

The Franklin Park Zoo and New England Aquarium are two of Chupasko’s sources, but her usual workday is consumed with mammals far more mundane than pygmy hippos or zebras. Dubbed the “roadkill queen” for her eager acquisition of the fauna of New England, Chupasko regularly collects rabbits, beavers, otters, foxes, coyotes, moose, and the occasional bear for study by researchers at the MCZ. Environment police and Division of Fish and Wildlife biologists bring her notable specimens, and she’s made trips to the Chiricahua Mountains in Arizona, Nicaragua’s cloud forests, and tropical forests in Uganda to diversify her collection with farther-flung mammals.

Chupasko explains that these mammal specimens are vital to research in evolution, taxonomy, ecology, conservation, and even medicine. In light of recent species declines, they document and measure biological diversity.

At the center of Chupasko’s lab is a steel table, where she does the initial preparation of her specimens. “You can slap a dolphin or a black bear on there, no problem,” she says, although the zebra she recently acquired from Franklin Park Zoo was too large to make it to the table so she did her work on the lab’s concrete floor.

Chupasko’s job is not for the queasy. Some of her specimens remain relatively intact, pumped with a preserving solution then stored in jars of alcohol that line the shelves of her lab like some scary grandma’s pantry.

Most of her collection, however, goes under the knife. Chupasko first gathers as much information as she can about the mammal, recording measurements and other data in a notebook. Blending science with sleuthing, her necropsy can discern her specimen’s diet, health, and even sex life (useful for population studies and to help set hunting and trapping limits). Careful collection of this data is crucial to scientists’ future research on the specimens.

Next, Chupasko decides what parts of the mammal are most valuable to the museum. “I try to save as much of the animal as I possibly can for the kind of research that’s going on now,” she says. DNA research and other recent biochemical and molecular advancements now mandate that she capture up to 20 tissue samples of each beast she prepares – easier from a moose or a hippo than a field mouse.

She stuffs and saves the skins of most small and medium-sized mammals and sends larger hides to a tannery for final preservation. Because bones, in particular skulls, are almost always saved, much of Chupasko’s operation is fleshing the animal, scraping muscle and fat away from the bones and hide in what might be hours of backbreaking – and potentially stomach-turning – work. “Thank God your olfactory senses tire quickly,” she says. “After a while, it’s like, ‘What zebra?’”

After fleshing, Chupasko dries what tissue remains on the bones under lamps in a climate-controlled room. Making what she calls “beef jerky on the bones” prevents the lingering flesh from rotting during the process of preparation, which could take up to a week.

For the final cleaning of the bones, Chupasko goes back to nature, putting her jerky-skeletons into screen-lidded bathtubs full of meat-loving dermestid beetles, commonly used by museum preparators. Chupasko’s beetle colony is especially vigorous and can clean a coyote in about two days.

About that hippo

Focused on the hippo dilemma, Chupasko calls the museum and confirms that the zoo’s pygmy hippo would make a prize catch. The museum has a mounted skeleton on exhibit but no pygmy hippo in the collection that scientists could study. “Also, something like this is rare in the wild,” says Chupasko. This windfall from the zoo represents a rare opportunity, and Chupasko must figure out how to take advantage of it.

Although she has occasional graduate student assistants, Chupasko’s Bedford lab is a one-woman shop. To wrestle the 700-pound zebra from the back of her pickup truck downstairs to her lab, she marshaled assistance from the Field Station’s building superintendent and graduate students – and even recruited a curious bystander.

Storing her specimens before she can prepare them requires similar creativity. One large mammal will fill her freezer at the Field Station, so Chupasko often brings the overflow to a chest freezer in her garage at home. She no longer utilizes her kitchen freezer, however, after a skunk ruined its entire contents. Indeed, a dorm-sized fridge in her lab bears a cautionary sign: “Food only.”

Chupasko and the Franklin Park Zoo veterinarian hit upon a solution: the zoo staff will flesh the hippo, leaving much less animal for Chupasko to transport and store at the Concord Field Station. Chupasko corrals supplies – latex gloves, knives, a hacksaw for bones – and heads to the zoo in Dorchester.

Lifelong love of animals

The beetles and bones of the Concord Field Station are tame in comparison to the scene behind the zoo’s veterinary station. There, Chupasko and several zoo workers are trimming away the hippo’s flesh, each of them working on a different quadrant of her former 695-pound body. Crimson rivulets run down the driveway; the scene could turn even the heartiest carnivore vegetarian.

“I always loved animals as a kid,” says Chupasko, her carving knife poised over the hippo’s shin. “I had so many pets that I’m sure I drove my mom crazy. Every weekend I’d go to the zoo.” In high school, the Pittsburgh native set her sights on being a veterinarian, but a college professor showed her how to prepare animal skins for study and she was hooked. In graduate school, she studied with the curator of a mammal collection and made her first collecting trip to the Amazon Basin in Peru. She’s worked at the MCZ since 1989.

Once a vegetarian herself, Chupasko knows that some may find her job unsavory or even offensive. She says that her career is a result of her love of animals, not at odds with it. “All life is important, not just the cute fuzzy animals,” she says. “To me, all living things play a vital role in keeping ecosystems alive and functioning.” By collecting and preparing mammals for further study, Chupasko sees herself as serving an important function in the continuation, not destruction, of the animals she loves.

Contact Beth Potier at beth_potier@harvard.edu