Letters, drawings, make ‘Windshield’ clear

Museums by definition preserve and display the past, but the new exhibition at the Sackler goes beyond the mere presentation of venerable objects.

“Richard Neutra’s Windshield House” is an immersion experience – not in the distant past, but one still in living memory. It is that temporal proximity of a world of brave aspirations and untarnished dreams, of bold designs and avant-garde lifestyles, close enough almost to reach out and touch, and yet relegated, literally, to the ashheap of social and architectural history, that makes this exhibition so eerie and so fascinating.

Richard Neutra (1892-1970) was a Vienna-born architect whose modernist designs reflect a vision similar to that of his slightly older contemporaries Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier.

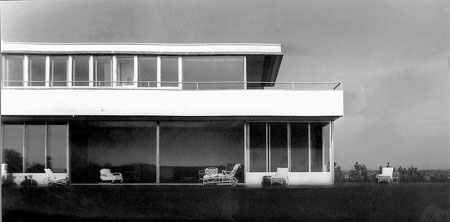

It was a vision that expressed itself in a characteristic vocabulary – flat roofs, industrial materials, open floor plans, and lots of windows.

Neutra moved to California in the 1920s, where he constructed a number of spectacular homes in the hilly country around Los Angeles, the most famous of which is the so-called “Health House,” designed for naturopath physician and writer Phillip Lovell. The house incorporated special kitchen and bathroom equipment as well as areas for outdoor sleeping and nude sunbathing.

Then in 1937, Neutra met John Nicholas Brown and his wife, Anne Kinsolving Brown. The Browns had sought Neutra out after making a careful study of contemporary architects and inspecting houses he had built on the West Coast. They wanted Neutra to build them a summer “cottage” on Fishers Island off the coast of Connecticut.

For the Browns, the windswept island was a wilder more secluded alternative to the fashionable seaside town of Newport with its exclusive yacht clubs and summer mansions. John Nicholas Brown’s ancestors had settled in Rhode Island in 1638, thriving as merchants and manufacturers. A family member founded Brown University in Providence. John Nicholas Brown broke with family tradition and attended Harvard (Class of 1922) because he was afraid professors would be too easy on him at the university that bore his name.

Brown was far more passionate about the arts, and particularly architecture, than he was about running the family business. He met his match in Anne Kinsolving, who, when she married Brown in 1930, was already, at the age of 24, a published poet, a professional musician, and a reporter for the Baltimore News. Her reportorial exploits included, among other things, jumping into a dumbwaiter to gain access to a debutante who had been arrested for theft and flying upside down over the Washington Monument with a World War I fighter pilot.

The Browns were the archetypal modern couple, and they wanted a modern house. John Nicholas Brown was also the epitome of the informed client. Not only did he and his wife personally tour Neutra’s previous constructions, Brown assiduously studied contemporary materials and building methods. Neutra, who believed that a house should be designed to suit its owners’ lifestyle, welcomed the Browns’ involvement in the house, called “Windshield.”

The evolution of Windshield’s design, carried on in letters and drawings, represents what may be the most extensive and best-documented collaboration between designer and client in architectural history. Many of these original drawings, along with quotations from the letters, are displayed in the exhibition.

The house was completed in 1938 at a cost of $218,000, making it at the time the most expensive modern house in the country. But the Browns got a lot for their money. The square footage was 14,500, with quarters for servants and an abundance of space for the Browns and their three children to enjoy their summers.

“The music room is so beautiful and view from it so inspiring that we cannot worry too much about what the fall weather may bring,” Brown (ominously, in retrospect) wrote to Neutra soon after the family moved in.

That September an exceptionally powerful hurricane roared up the East Coast and lifted Windshield’s flat roof off its moorings. Many of the aluminum casement windows imploded and damage to the interior was extensive. J. Carter Brown, John Nicholas Brown’s eldest son, recalls a snapshot of his father lying down amidst the wreckage, his hat over his face, apparently crying.

That winter, Brown had the house rebuilt, with advice from a team of Massachusetts Institute of Technology structural engineers. The Browns moved back in, but as the children grew and the family’s needs changed, they occupied the house less and less. They finally sold it in 1963. Then on New Year’s Eve 1973, a fire started in the house while the owners were having drinks at a neighbor’s. Firefighters arrived, but were unable to gain access to sufficient water, and the house burned to the ground.

The exhibition at the Sackler, a collaboration between the University Art Museums and the Graduate School of Design, brings Windshield back to life in a way that is not only extraordinarily thorough but strangely evocative. Confronting visitors as they enter is a replica of the aluminum-painted shiplap siding that covered the house. To the left is the word “Windshield” in aluminum letters, a rescued artifact that hung from a post at the head of the driveway.

There are architectural models, artwork from the house, and a huge black-and-white photo mural of the beloved music room with a view of the bleakly beautiful landscape through the floor-to-ceiling windows. On a platform in front of the photo stand replicas of the modern furniture on which the Browns once lounged, creating a diorama effect that makes the room’s charm almost palpable.

The original colors of the interior have been recreated through consultation with J. Carter Brown, and these colors have been used on the partitions that divide the exhibition’s interior space. Finally, a loop of Brown family home movies can be seen playing continuously on a video screen, showing Windshield during construction, after the hurricane, and during its brief life as Fishers Island’s most futuristic vacation cottage.

The exhibition also resurrects a lost chapter in the history of a modern architect.

“In the career of Richard Neutra it is a watershed building,” said Dietrich Neuman, the exhibition’s curator, a professor of architectural history at Brown University. “It was a crucial experience. He learned a lot from this house which helped him define architectural theory more clearly than before.”

The exhibition will remain at the Sackler Museum through Jan. 27.