Identity politics in late antiquity

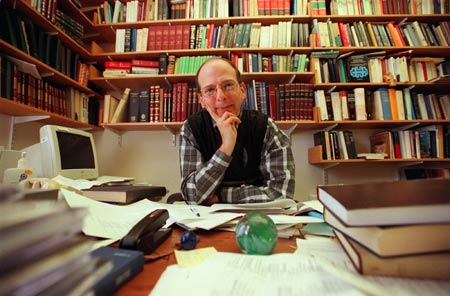

Self-definition is not a new problem, Shaye Cohen says

For most people, the world of late antiquity can hardly be said to be a subject of pressing and immediate concern, unless of course it happens to be the setting for a film about an indomitable gladiator or the internecine struggles of decadent aristocrats.

Surely then, the efforts of one group of people within the Roman world to reconstruct their shattered identity through literary means following a crushing military defeat would seem on face value to have even less chance of grabbing the attention of non-specialists.

- Education:

1966-1970 Yeshiva College, B.A. in Classics; 1970-1974 Jewish Theological Seminary, M.A. in Judaica and rabbinic ordination; 1970-1975 Columbia University, M.A. and Ph.D. in ancient history. - Career highlights:

1974-1991 Jewish Theological Seminary, promoted to full professor 1986, Dean of the Graduate School 1987-91; 1991-2001 Brown University, Ungerleider Professor of Judaic Studies and Professor of Judaic Studies; 1998-99 Lady Davis Visiting Professor of Jewish History, Hebrew University, Jerusalem; 1999 Louis Jacobs Lecturer, Oxford University. - Books:

“Josephus in Galilee and Rome: His Vita and Development as a Historian” (1979); “From the Maccabees to the Mishnah: A Profile of Judaism” (1987); Editor, “The Jewish Family in Antiquity” (1993); Co-editor (with Ernest Frerichs) “Diasporas in Antiquity” (1993); “The Beginnings of Jewishness” (1999).

But for Shaye Cohen, the recently appointed Littauer Professor of Hebrew Literature and Philosophy in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, the subject of Jewish identity from the first century B.C.E. to the third or fourth century of the Common Era is not only fascinating in itself but has many parallels with the efforts of people in our own pluralistic and secular society to preserve ethnic or religious identities.

“The question of who is a Jew is actually of broader interest because American society is in fact bedeviled by this question, not only who is a Jew, but who is black, who is Native American, who is Chinese, and what do these categories mean, and how do we have a society that claims to be unified on the one hand and on the other celebrates difference?”

Cohen’s colleagues recognize the innovative nature of his work and are delighted that he has joined the department.

“He is widely recognized as one of the leading historians of the period from the Maccabees to the Mishnah – four or five hundred years of Jewish history,” said James Kugel, the Harry Starr Professor of Classical, Modern Jewish and Hebrew Literature and professor of comparative literature. “He asks very provocative questions, like, What was Jewish identity in this period? Can we put our finger on the point when it changed from being a resident of a certain territory and became an adherent of a religion?”

Peter Machinist, the Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages, praised Cohen for his familiarity with both classical literature and the difficult, often confusing texts of early rabbinic Judaism.

“The Jewish sources from this period are immense in quantity and very hard to make sense of, but he has mastered them beautifully. But at the same time he’s a first-rate classical scholar, which you need to understand the larger world in which Judaism took shape,” Machinist said.

Cohen’s interest in questions of Jewish identity came about through the intersection of his training as a historian with his own personal concerns as a 20th century Jewish American.

“I am part of the American Jewish community,” he said. “That’s part of who I am, my own self-definition. And American Jews are very much concerned with self-identity – who is a Jew, the future of the community, the boundaries between Jews and gentiles. So at some point about 20 years ago, it occurred to me, gee, these are interesting questions. Wouldn’t it be fun to see how the same questions might have played out in the period of antiquity, the period of my alleged expertise?”

One result of this project is his book “The Beginnings of Judaism” (University of California Press, 1999), in which Cohen remarks on the parallels between our world and the world in which Jews lived before Rome’s crushing defeat of the Jewish revolt, culminating in the traumatic destruction of the great Temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E.

Before this defeat, Jews lived under the Pax Romana, in which a multiplicity of faiths were tolerated. The Temple was presided over by a high priest, but he had very little power to compel Jews to worship or to specify how they worshipped. Then as now, participation was voluntary.

Cohen’s book compares texts from this earlier period – the writings of Greco-Jewish writers like Philo and Josephus, the Qumran texts (Dead Sea Scrolls), and the books of the New Testament (written at a time when Christianity was to a large extent a radical offshoot of Judaism) – with later texts like the Mishnah and Tosefta, written chiefly in Aramaic and Hebrew. It was during this later period that the rabbis, through their writings and through their growing influence within the Jewish communities of the early Diaspora, became the dominant force in Jewish life.

“Nowadays we’re living in a post-rabbinic world, after rabbinic hegemony has more or less disappeared, and most Jews do not accept the self-evident truths of rabbinic Judaism and rabbinic norms, while the period of antiquity is pre-rabbinic. The rabbis had not yet achieved hegemony. The rabbinic system had not yet been codified and systematized and institutionalized.”

But where did the rabbis come from and how did they achieve such influence? The question is almost impossible to answer given the fact that virtually no biographical material exists on these individuals who had such a profound effect on the development of the religion. But it is possible to make inferences about the nature of their contribution.

“Rabbinic Judaism and rabbinic texts clearly come from somewhere. They didn’t just begin from scratch around the year 100 or so. They carried forward a legacy of what had been there earlier. But by the same token there is a lot there that’s new. The rabbis are not creating a new Judaism – I think that’s too strong – but they certainly are creating a new Jewish culture.”

Cohen shows how the rabbis set down explicit, systematic rules and procedures for situations characterized in earlier times by ambiguity or diversity. For example, they defined for the first time the procedure by which gentiles could convert to Judaism, and they established the principle that Jewish identity is inherited through the mother, thus clarifying the status of children of mixed marriage.

“If you look at pre-rabbinic texts, they do not yet have anything remotely approximating the clarity and systemization that we find in rabbinic texts. And I as a historian argue that the rabbis made it up. It’s not ancient tradition from Mt. Sinai. The rabbis are creative, they are thinkers, they are innovators, they are alive. They’re not just museum custodians, they are creating something.”

More recently, Cohen has been studying the place of women in Judaism, focusing this time on European Judaism in the high Middle Ages. He has written several articles on the menstrual taboo in Judaism and has recently begun work on a book-length project on gender differences within the religion, focusing especially on the ritual of circumcision.

Much of the material he is studying comes out of a centuries-old debate between Christian writers attacking Judaism and the response by Jewish writers defending their religion. One point concerns the issue of baptism. Christian writers have said that their religion is more inclusive because they baptize both men and women. Jews only circumcise men. How then do women become Jews?

Most of the Jewish writers answer this question from a traditional, paternalistic viewpoint: men are the ones who bear the full weight of the Commandments and the Torah while women are adjuncts. But there are other, more imaginative answers.

Cohen was particularly struck by the writings of one 12th century rabbi who said that women don’t need to be circumcised because they follow the regimen of menstrual purity, the cleansing monthly bath or mikvah. His argument thus equates menstrual blood with the blood of circumcision, an idea that has been elaborated by modern anthropologists.

“That I thought was mind-blowing, not only because it anticipates anthropology, but because it takes menstrual bleeding, which in rabbinic culture had always been a powerful symbol of impurity and pollution and somehow gives it a positive valence and says that it is now covenant. It doesn’t mean that the rabbis are radical freethinkers, but within the confines of the tradition they certainly are intellectually alive.”