Artists at “Sprung From Ruins” confront post-Sept. 11 world

‘Everything became deeper’

None of the artists who participated in the Nov. 9 panel discussion “Sprung From Ruins” presumed to offer words of wisdom about how the arts might heal or soothe or put right the terrible damage wreaked on this country on Sept. 11.

A few, in fact, mocked the idea that artists possessed the requisite power to exert such influence. And so, in the sense that no positive conclusion emerged, the event, sponsored by the Office of the Arts and subtitled “A Panel Discussion on the Arts During a Time of Crisis,” might be considered a failure.

And yet one important fact did come through – none of the artists on the panel was stopped by the events of Sept. 11. All of them went on doing what they did. Or if they encountered a blockage in their output, it was of the most temporary sort.

Singer/songwriter James Taylor was in the middle of a tour and decided to go on performing. “If anything, it made me more conscious of what I was doing every moment. Everything became deeper. I was more concerned about the audience reaction, what state they were in,” he said.

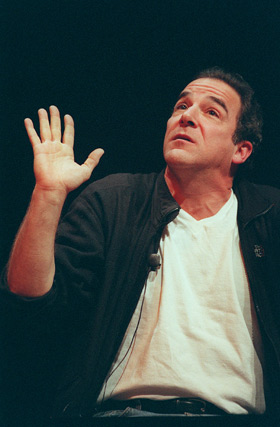

Singer/actor Mandy Patinkin went on with his tour as well, although he did change the ending of his act, a medley of songs that he described as “a prayer” for peace in the Middle East. After Sept. 11 he toned down the presentation, eliminating some of the more obvious stage business that had accompanied the songs. He did so, he explained, “because I wanted the prayer to be heard.”

Playwright John Guare said that after the nightmare of Sept. 11 he felt “absolutely paralyzed, like a block of ice or stone.” But soon afterward he found himself at his computer, feverishly writing a play “that had been banging around in my head but that I couldn’t get hold of.” Burying himself in his work “wasn’t denial,” he said. “But the times didn’t give me anything else to do.”

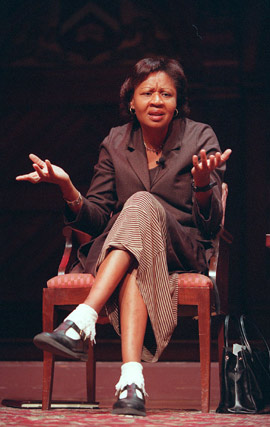

Fiction writer and memoirist Jamaica Kincaid went Guare one better. “I wasn’t stopped by it at all,” she said. “I worked all through it because when I was finished someone would give me a check which would allow me to pay my bills.”

Choreographer and artist Trisha Brown said that at first she couldn’t work because “my work is located in my body, and my body was in shock.” But in the aftermath of the attacks, she too went on tour, lecturing and working with students.

“Since then, a strange thing happened,” she said. Invited to create a museum piece, she confronted a large piece of paper taped to the floor of her studio, feeling “wigged out and scared.” Nevertheless, she attacked the paper armed with charcoal and pastels, and five minutes later, “I’d created the most beautiful thing I’d ever drawn.”

Visual artist Elizabeth Murray told a similar story. She said on the day of the attacks, there was “a tremendous feeling of death” in her Manhattan neighborhood. The next morning, however, she “went to the studio and started to work with a great deal of energy.”

She went on to say that “deep down, most artists are on the edge of feeling that what they do is absolutely meaningless – and that’s the fun of it.”

There was disagreement as well. Kincaid expressed consternation that the attacks and their aftermath “was turning into a moment about American suffering. We’re in danger of saying, ‘I’m so glad it happened because it’s brought us all together,’ and suddenly it’s all about us. This is something bigger than how we feel.”

John Rockwell, editor of the New York Times Arts and Leisure section and the moderator of the panel, countered, “The fact that it happened to us doesn’t necessarily highlight our selfishness.”

Guare denied that art can change anything. “All we can do is tell our truth whatever that truth is. You can’t go out and write a piece that will end human suffering or redistribute the wealth. All an artist can do is say that this is what it was like when I was alive.”

Kincaid replied, “We can’t handle the truth. The truth is we do a lot of terrible things in the world, and that makes it possible for me to have this nice skirt which I love. The truth is simply too much to bear.”

Patinkin said, “The point of art isn’t to hammer people over the head.” But he added that “as artists we have the privilege of an audience.” Artists can take advantage of that privilege by promoting the causes they believe in. He said that at the conclusion of his concerts he makes a short speech in favor of organizations he believes are doing good work, then stands in the lobby taking donations.

“I feel that if they can afford the price of a ticket, they can afford to spend two more minutes to listen to my speech,” he said.