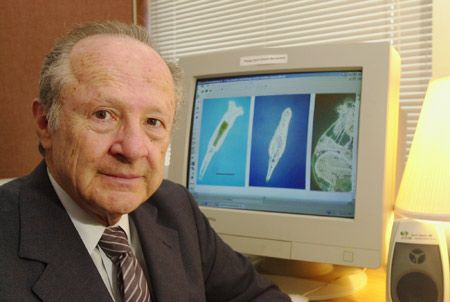

Anthrax expert Matthew Meselson speaks

Matthew Meselson, Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences, has been raising his voice in opposition to biological and chemical weapons since 1963. He investigated the largest known outbreak of inhalation anthrax in history, which occurred in the Soviet Union in 1979. Meselson co-directs the Harvard Sussex Program on Chemical and Biological Weapons Armament and Arms Limitation, an organization that has drafted a new international treaty on the production and use of such weapons.

I asked him about his experiences in the Soviet Union, what information about the present anthrax scare is reliable, and what actions people and nations can take to deal with this and other biological attacks.

Q: There’s so much information in the media about the threat of anthrax infection, some of it contradictory, what can a person believe or safely ignore?

A: In scrambling for bits of new information, the media sometimes put forth unconfirmed information in ways that readers may think comes from authoritative sources. For example, it has been repeatedly reported that it takes thousands of anthrax spores to cause a lethal infection. That’s wrong. Both theory and experiment suggest that even a small number of spores can do it, albeit with a very low probability.

Such unreliable information may cause people to think you need to get a whole nose full of spores before you have any chance at all of being infected. It’s not good news, but it is important in dealing with this outbreak that responsible officials understand the relation between anthrax doses and peoples’ responses.

I’ve sent an e-mail to many of my friends and asked them to forward it. It says, “believe nothing unless it comes from a U.S. government official who is involved in the laboratory investigations and who has sufficient scientific knowledge to know what he is talking about.” Journalists should identify their sources of information and attempt to determine if the sources have the scientific knowledge and the information to back up their statements.

Q: How easy is it to make anthrax into a weapon?

A: Some people say that it’s easy, that the technology is well known. But you should ask such people if they’ve done it themselves. Only someone who has done it can know how difficult or easy it is to do.

Getting hold of the spores is easy enough. Just go to a place where animals such as cattle or horses have died. However, there’s evidence that the spores sent through the mail come from a laboratory and were not newly isolated from soil or sick animals.

Maj. Gen. John Parker, who commands the Army’s medical research facility at Fort Detrick, Md., and who is a qualified scientist, has said that the spores sent by mail are a common type and relatively free of debris or contamination. That almost tells you it is a laboratory-made strain.

There are about a half dozen labs in the U.S. where people are licensed to work with disease-causing anthrax. And there may also be secret government projects where scientists working on biological defense are handling it.

However, there is no solid evidence I know of to point to an origin within the U.S., to Osama bin Laden, or to another country.

Q: Is there any difference between inhaled anthrax and skin anthrax?

A: The spores are the same. The only difference is the route of entry into the body.

Q: Can other drugs beside Cipro be used for treatment, and what natural defenses do people have against anthrax infection?

A: Maj. Gen. Parker has said that the strain now causing disease in the U.S. is sensitive to many antibiotics. These include penicillin, amoxicillin, doxycycline, chloramphenicol, and others. The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention’s Web site contains the whole list.

Hairs and so-called baffle plates in our nasal passages catch more than 90 percent of large spores, those bigger than 10 microns (about four-ten-thousandths of an inch). Mucus picks them up, and they are expelled when you blow your nose.

Particles that get into the lungs are also caught in mucus. This system pushes those that are bigger than about 5 microns into the back of the throat. From here, they are swallowed, or sneezed, spat, or coughed up.

If spores get deeper into the lungs, they might do nothing for several days or weeks. That means we might see delayed cases, as happened after the anthrax release in Russia in 1979.

Q: What did you learn when you studied that outbreak in Sverdlovsk that could be applied to the present situation in the U.S.?

A: In 1992 and 1993, we walked up and down a 3-kilometer (1.8 mile)-long path over which wind carried anthrax released accidentally from a Russian military facility. We confirmed the deaths of 66 people, and documented the cases of 11 who survived

None of these people were younger than 24 years. That occurred despite the fact that the cloud passed over schools, shops, and small houses, and that people 23 years and younger probably included almost half the population.

We checked reports from all over the world, but could find no cases of younger people being infected by inhalation anthrax. There are cases of cutaneous infection in children and young people, where spores enter cuts or breaks in the skin, but not of the inhaled variety.

We also looked at a similar disease, Legionnaires’ disease, and found a similar trend.

Maybe at high doses, everyone would get infected, but this suggests that at low doses young people would escape infection by inhalation.

[The Russian disaster is described in “Anthrax: The Investigation of a Deadly Outbreak” by Jeanne Guillemin (University of California Press). Guillemin, Meselson’s wife, is a professor at Boston University and part of the team that investigated the outbreak.]

Q: Would wearing a medical mask prevent inhalation anthrax?

A: That depends on the type of mask. It should cover your nose and mouth and block particles as small as 1 micron. (He reached into a drawer and pulled out a spongy mask that was less porous than the cuplike masks rescue workers and others wear to protect against dust.) These cost about $3 each.

Q: What can be done to counter the threat of using anthrax as a weapon?

A: There are seven international treaties that cover torture, airline hijacking, theft of nuclear materials, harming of diplomats, and so forth. We need an eighth that makes it a criminal act to use infectious organisms and biological toxins for hostile purposes.

The Biological Weapons Convention of 1972 prohibits such weapons, but stops short of establishing jurisdiction over foreign nationals who commit these offenses in other countries, and it does not deal with extradition, or require legal cooperation between countries in prosecuting offenders. The Harvard Sussex Program on Chemical and Biological Weapons Armament and Arms Limitation has prepared a draft convention that would make it a crime under international law for any person to knowingly develop, produce, acquire, retain, transfer, or use biological or chemical weapons. Any person who commits any of the prohibited acts anywhere would face prosecution or extradition.

Of course, there would be some nations that would not sign such a convention. However, it would still apply to their citizens if found elsewhere and would serve as a powerful deterrent. It would create a new dimension of constraint by applying international criminal law to hold individual offenders responsible and punishable should they be found in any country that supports the convention. Such individuals would be regarded as enemies of all humanity. The norm against biological and chemical weapons would be strengthened, deterrence of potential offenders would be enhanced, and international cooperation in suppressing the prohibited activities would be facilitated.