‘i ka nyé tan’ is Bambara for ‘You look beautiful like that’

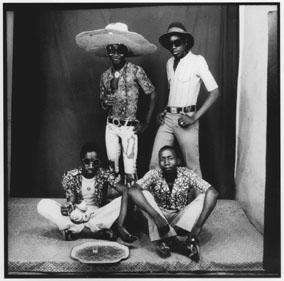

The photograph is titled “Amis des espagnoles” (French for “friends of the Spanish”). It was taken in 1968 by Malick Sidibé, and there is something oddly familiar about it.

Four slender young African men pose in hip-hugger pants and patterned shirts before a dark backdrop. Three of the four wear sunglasses, and the two who are standing wear hats, the one on the left a straw sombrero whose enormous tattered brim looks as if it has been gnawed by mice. The other two men sit cross-legged on a printed cloth, one of them looking up at the camera as he pours tea into a tiny glass cup on a tray.

Michelle Lamunière, a graduate student in art history at Boston University and an intern at the Harvard University Art Museums, has curated the new exhibition at the Fogg Art Museum, “You Look Beautiful Like That: The Portrait Photographs of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé.” Her comment on this picture crystallizes the vague sense of recognition it evokes.

“At this point you’re beginning to see young people breaking away from traditional roles and using photographs as a vehicle for self-expression. I think here you can see the influence of record album covers.”

Of course! It is 1968, and on hundreds of album covers groups of hirsute young men in eclectic outfits challenge record buyers with provocative expressions and postures. It’s the Baby Boom revolution, and it’s happening not just in Britain and the United States, but in places like Bamako, Mali, as well.

The photograph reminds us that by the late 1960s we truly are living in Marshall McLuhan’s global village, that images of The Who and Sly and the Family Stone are traveling to all corners of the globe and influencing the way young people in West Africa wish to present themselves.

“It’s not so much that they’re mimicking the West,” Lamunière says. “They’re embracing modernity along with the rest of the world.”

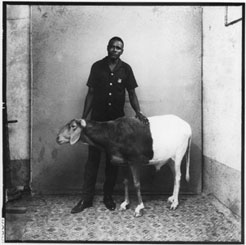

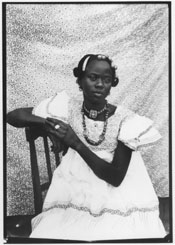

The Fogg Museum is currently showing the work of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, portrait photographers from Mali, West Africa. While it is evident that the aesthetic value of these photographs is very high, it is also true that their rootedness in history, in culture, and in the personal stories of their subjects is what lends them special interest. These portraits of largely anonymous Africans convey a vivid sense of society in transition.

The Fogg Museum is currently showing the work of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, portrait photographers from Mali, West Africa. While it is evident that the aesthetic value of these photographs is very high, it is also true that their rootedness in history, in culture, and in the personal stories of their subjects is what lends them special interest. These portraits of largely anonymous Africans convey a vivid sense of society in transition.

The story of that embrace begins in the late 19th century with postcards by European photographers showing scenes of exotic Africa (a selection of which is included in the exhibition). But here the bare-breasted women and aloof, posturing men are the objects of the photographs, not their subjects. That emphasis was beginning to change in the 1930s when Keïta, the older of the two photographers, began to take pictures.

Born circa 1921 and trained as a furniture maker, Keïta first became interested in photography when his uncle gave him a Kodak box camera. He began photographing family and friends and developing his skills through contact with older photographers. In 1948, he opened his own studio in a bustling section of Bamako close to the train station.

His clients were members of Bamako’s “elite” class – office workers, shopkeepers, government employees, politicians. Often, having a photograph taken was a way of creating visual proof that one had found a place for oneself in the modern world, that one had made it. Many of Keïta’s clients pose wearing new clothes, a new hairstyle, or sitting on a new motorbike. And when these accoutrements of success were lacking, Keïta would outfit the sitter from his prop collection, a service that is evident from the repetition of the same necktie or wristwatch from photo to photo.

As Keïta himself put it, “To have your photo taken was an important event. The person had to be made to look his or her best.”

Sidibé learned his craft as an apprentice to a French photographer in Bamako. In the late 1950s, he began to make his reputation taking pictures at parties and social gatherings, but he preferred portrait photography because it gave him more control over the finished product.

It is worth mentioning, however, that neither Keïta nor Sidibé thought of themselves as artists during the major part of their careers, although they are proud of their work and consider the final result beautiful. Their primary goal was to please their customers – hence the title of the exhibition, “You look beautiful like that,” a translation of the Bambara phrase i ka nyè tan.

In the essay she has written for the exhibition catalog, Lamunière quotes the critic Martha Rosler’s assertion that “the meaning of photographs rests in their rootedness in the stream of life.” While it is evident that the aesthetic value of these photographs is very high, it is also true that their rootedness in history, in culture, and in the personal stories of their subjects is what lends them special interest.

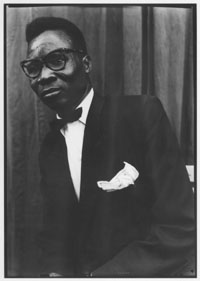

Often it is the details of dress, setting, and posture that convey this information. One portrait by Keïta made in 1958, for example, shows a young man in thick-rimmed glasses wearing a white, double-breasted jacket with a fountain pen clipped to the breast pocket. In his left hand he conspicuously holds an artificial flower on a wire stem.

One critic has suggested that the man may be identifying with French Symbolist poets like Mallarmé and Verlaine whose work he would have read in the public schools of the former French colony.

Another photograph by Keïta shows a young man who looks forward rather than back in constructing his self-image. Staring intently into the camera, he leans one arm on a large radio and appears to adjust one of the knobs with his other hand, suggesting that he is fully tuned in to the modern world. He is also oriented to time in the precise Western sense, as evidenced by his wristwatch and the alarm clock atop the radio, all three of these devices no doubt furnished by the photographer.

Lamunière refers to the photographer’s studio as a kind of theater in which the subject can create the identity he or she wishes to possess. In the exhibition the photos are presented in the form of large-scale prints, but the original product would have been postcard size, convenient for mailing home to one’s village to show how well one is doing in the big city.

Also of interest is the way in which the photographers use simple materials to give their pictures a look that is uniquely African. While 19th and early 20th century studio portraits that might have served as models typically use a backdrop depicting an idealized landscape or classical interior, photographers such as Keïta and Sidibé most often pose their subjects in front of an assertively patterned cloth, frequently with another strong pattern on the floor. In many cases, the subject’s clothes add additional striking designs, creating a visual buzz that somehow enhances rather than detracts from the sitter’s presence.

Taken as a whole, these portraits of largely anonymous Africans convey a vivid sense of a society in transition, of individuals taking their first steps toward a new and uncertain future and leaving behind traditional identities that have sustained them for centuries. What gives the exhibition its universality is that this is a path which, for better or worse, all of us are taking.

Most of the photographs in the exhibition are from the collection of Jean Pigozzi ’74. They will remain in the Straus Gallery until Dec. 16. On Wednesday, Oct. 10, Malick Sidibé will come to Harvard to talk about his work, followed by a lecture on African photography by Christraud Geary of the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution. The event will take place at 6 p.m. in the Sackler Museum lecture hall. On Saturday, Oct. 13, at 2 p.m., Michelle Lamunière will give a gallery talk at the Fogg on the work of both photographers.

Contact Ken Gewertz at ken_gewertz@harvard.edu