Swanson’s work recognized

Undergrad is first Harvard student to win Swearer Student Humanitarian Award

This is how Jordan Swanson is spending his last summer as a Harvard undergraduate: June in Bangladesh as a U.S. State Department intern investigating human rights abuses, July and August in Thailand conducting malaria research.

In between, Swanson made a flying visit to Minneapolis to accept the Howard R. Swearer Student Humanitarian Award. The award recognizes an AIDS awareness program Swanson founded and directed last year in Honduras.

Named for a former president of Brown University, the award is given by Campus Compact, a national coalition of more than 740 college and university presidents committed to the civic purposes of higher education. Swearer was one of the founders of Campus Compact in 1985.

Swanson is the first ever Harvard student to receive the award. In his nomination letter, former President Neil L. Rudenstine described Swanson as “a caring, concerned, and dynamic man who will continue to make a positive impact in our global community,” adding that Swanson “embodies well the spirit of this award.”

Swanson was glad to receive the award. With it comes $1,500 worth of support for his Honduran AIDS program, Jóvenes en Acción (Youth in Action). But he is a bit leery of accepting the label the award implies.

“I don’t know quite what responsibilities go with the title of Humanitarianism,” he said. “I think we can all be humanitarians. If we all just acted on our compassionate human nature a bit more, engaging in the activities that interest us with an eye for how they can complement the needs and abilities of others, the humanitarian benefit will happen as a side effect.”

A history of science concentrator from Bainbridge Island on Puget Sound near Seattle, Swanson first gained experience helping others in need when he worked as a lifeguard and a medical first responder in high school. But his interest in medicine took on a global perspective as the result of certain key experiences after he enrolled at Harvard.

Swanson’s first economics course, Social Analysis 10: “Principles of Economics,” woke him up to the enormous disparities between the industrialized nations and the developing world. It also gave him an idea of the most effective way of making a difference.

“Economics dictates that you invest at the point where you have the greatest margin of difference. In my perspective, that margin for health care improvement is especially obvious in places like Honduras, but it is equally great much closer to home, as in lower-income areas of Boston. And I get really shaken up watching children waste away from asthma when it happens a few miles from where we live, where we have a more neighborly responsibility to help each other.”

In addition to Swanson’s work in Honduras, the Swearer award recognizes his contributions as the former director of Harvard’s Asthma Swimming Program, which teaches specialized swim lessons to help cure young asthma sufferers in Roxbury and Jamaica Plain. The program has gained national media coverage, and the curriculum is being duplicated in sites across the country.

A second crucial experience was undergoing wilderness EMT training the summer after his freshman year. It occurred to him that the principles of wilderness medicine – improvising tools and techniques with what is on hand – are also the essentials of Third World medicine.

Swanson also wanted to live in a developing country and to gain medical skills through first-hand experience, so he began sending letters to NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) asking for a volunteer position. He got only one positive response to the many inquiries he sent out. That was from World Visions Honduras, which agreed to take him on for the summer to work in the organization’s village-based health program.

Swanson was sent to a rural area in the mountainous southern part of the country to serve as a pediatric field medic with a surgical and medical brigade. He proved his worth when he discovered a dead chicken at the bottom of a well and identified it as the probable cause of an outbreak of diarrhea. The incident made him realize that an effective health program had to seek out and address the root of the problem rather than simply diagnosing illnesses and dispensing drugs.

Realizing that World Vision had been slow to confront the problem of AIDS in Honduras (which has the second highest AIDS level in the Western Hemisphere, after Haiti), Swanson designed a community-based health education program for adolescents. He outlined the program to World Vision officials, but was shocked the following January when they decided to implement it and make Swanson its coordinator.

Swanson spent the spring of 2000 helping to get a team of American and Honduran medical workers ready to for the field. As one of the youngest of the group (which included teachers, epidemiologists, community development experts, public health officials, and his sister, Annika, an undergraduate at Yale), Swanson was hesitant to assert his authority. He soon learned, however, that given the time constraints, it was essential for him to make autonomous decisions, and for the most part he found that the other team members were willing to go along with this arrangement.

“We all pushed the envelope of our abilities, myself probably more than the others. But through it all, even when I was the explicit leader, we maintained a team effort through and through. I feel I was the transparent face in front of a team that exhibited extraordinary talent, creative problem-solving, and uncompromising sensitivity. The team members were the real humanitarians, and I merely channeled their brilliance.”

Swanson compares his role as coordinator to being “a bungee cord” between team members, funding sources, and World Vision officials, dealing on a daily basis with communication difficulties, differences of opinion, and simple confusion.

Swanson had to juggle these responsibilities along with his course work. The worst moment came on the eve of his organic chemistry final when he received a message that the project had been canceled. The message later turned out to be a misunderstanding, but in the meantime Swanson had to meet the challenge of remaining calm under pressure and dealing diplomatically with all concerned.

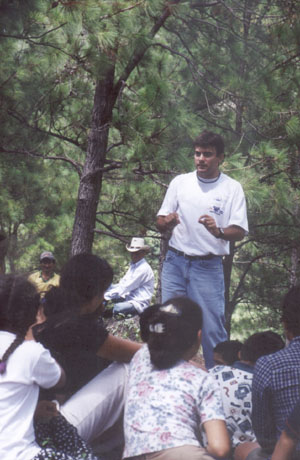

He had been warned that the villagers he hoped to reach would not accept intervention by foreigners and would never tolerate open discussions about sex, but these fears proved unfounded. Swanson’s group began by listening rather than preaching, conducting interviews with hundreds of Honduran youths.

At the same time, they overcame the suspicions of adults by making information available to parents and community leaders and including them in discussions.

“We had to make a leap of faith that at the end of the day everyone involved had the same interest in empowering children – not by selling them on our values, but by giving them the tools and the information to develop their own values and act on them,” Swanson said.

The leap of faith paid off.

“After listening to and treating the community members respectfully and in an ongoing manner, we gained their trust and cooperation to the absolute utmost.”

This wasn’t just politeness. It was necessary for the project. Swanson feels that this was the biggest way Jóvenes en Acción differed from past health interventions. Both the Honduran and American team members wanted to avoid entering the scene as outside experts who had all the solutions to the people’s health problems beforehand, a negative perception often expressed about development projects.

“We just acted like genuine students. We listened, we asked for help, and then we reacted.”

By the summer’s end the various personnel had learned their jobs so well that Jóvenes en Acción had become self-sustaining. It now reaches more than 1,000 Honduran youths. Swanson’s realization that his creation had taken on a life of its own played a key part in his decision not to return to Honduras this summer, but to seek out new experiences in Bangladesh and Thailand.

Swanson is currently applying to medical schools, but is also considering taking a P.P.E. degree, a British program combining philosophy, politics, and economics. In any case, he sees the practice of medicine, perhaps as a pediatric surgeon or trauma specialist, as playing a key role in his future career. Once he has acquired these clinical skills, he believes he will be prepared to make a contribution to health policy and to bring medical attention to those who need it most.

“I feel personally challenged to work with underserved populations, either in rural or urban areas, domestic or international. Medicine applied at the margin, where it can effect the greatest improvement in welfare, and conveys a high benefit to the community.”

Contact Ken Gewertz at ken_gewertz@harvard.edu