Unique film of Impressionist Renoir at work is found at Department of Comparative Literature

For 44 years a small disc-shaped metal canister rested in a closet at the Comparative Literature Department’s office in Boylston Hall. Nobody opened it. Nobody knew what it was.

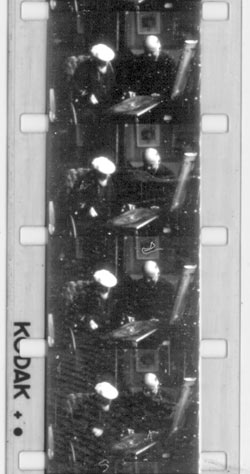

Then, this May, when the department participated in a University-wide initiative to inventory artworks and other significant items, the canister was found to contain about 100 feet of 16mm movie film. The silent, black-and-white film showed an elderly man in a wheelchair painting a picture. It also showed him interacting with another man and with a woman.

A note taped to the lid of the canister offered an explanation. The man in the wheelchair was Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the French impressionist painter (1841-1919), whose severe arthritis crippled him during the last years of his life, but did not stop him from painting. The other man was Ambroise Vollard, a well-known art dealer and writer. The woman was “La Boulangère,” Renoir’s servant and occasional model.

The note also suggested that the film was shot by Renoir’s son, Jean Renoir (1884-1979), who was later to direct such classic films as “Grand Illusion” and “The Rules of the Game.” In 1917, the probable date the Renoir film was made, Jean was at his parents’ house recovering from a leg wound he sustained as a soldier in World War I.

But how did the film get to Harvard? As the note explained, it was given to the Comparative Literature department by Jean’s son, Alain Renoir, who earned his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1956 with a dissertation on the medieval English poet John Lydgate. Alain Renoir is now a professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. When department chairman Jan Ziolkowski realized that the film was a unique and historically important document, he decided to give it to the one institution on campus qualified to treat it with the care and expertise it deserved – the Harvard Film Archive. Archive curator Bruce Jenkins was thrilled at the unexpected discovery.

“It’s undoubtedly the only moving image that exists of Renoir painting … or any of the great impressionists, for that matter. There are some motion pictures of famous generals and members of royalty from this period, but movies of painters are extremely rare.” Jenkins has begun researching the history of the film. He is certain that the 16mm print is not the original version of the film because this format did not come into use until the late 1920s. He speculates that the original was shot on 35mm nitrate film, then printed on 16mm Kodak safety film sometime in the early 1950s. The nitrate film on which virtually all early movies were printed was highly flammable and often self-destructed in the can.

Although Jenkins believes it would be wonderful if the film really were an early work by the painter’s filmmaking son, Jean, he doubts whether this is the case. The film predates Jean’s earliest known forays into professional filmmaking by about eight years, and while the lighting, composition, and other technical aspects seem professional, there is no evidence of Jean Renoir’s characteristic visual style.

But Jenkins does consider it possible that the making of this film had an influence on Jean Renoir’s later career. In his autobiography, Jean describes himself as a fanatic movie enthusiast at this period, enamored by Charlie Chaplin’s early films. One can imagine how fascinated he would have been by a professional cameraman coming into the house to film his father working.”Maybe it was the experience of seeing his father being filmed that sparked Jean’s later interest in filmmaking,” Jenkins said.

The documentation that was found with the film states that the negative was owned by Gaumont Actualités, one of the earliest French cinema production companies. Jenkins has checked a listing of Gaumont’s output and found no mention of the Renoir film, although it may have been part of a newsreel or some other longer work.

But it is also possible that Harvard’s version is the only copy in existence. Jenkins plans to do further archival research in the hope of answering this question, but in the meantime he intends to treat the film as a unique and irreplaceable object.

“We want to make certain it’s not a unique print before we show the film in public,” he said. “It will probably be six or eight months or maybe a year before we get to that stage. I can imagine presenting it as part of a program of rare films of other artists at work.”

The Harvard Film Archive, located in the lower level of the Carpenter Center, has a collection of nearly 8,000 films (including 28 by Jean Renoir) and would be interested in hearing about any other films that may turn up on campus.