Filmmaker immortalizes ‘immortal’ cells

On Oct. 4, 1951, Henrietta Lacks died of cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore. Poor and black, the daughter of tobacco pickers in rural Virginia, and mother of five, the 31-year-old woman might have died in obscurity, forgotten by all but her immediate family and friends.

But Henrietta Lacks will live forever – in laboratories and research centers worldwide that use her unique, immortal cells for medical research. The cells of her cancer, known as HeLa cells, were the first human cells discovered to thrive and multiply outside the body, seemingly forever, allowing researchers to conduct experiments previously impossible. HeLa cells were instrumental in creating the polio vaccine and may, one day, help cure cancer. In what has become a billion-dollar industry, HeLa cells have traveled around the world and been shot into space.

For independent filmmaker Charlene Gilbert, a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, these facts about Henrietta Lacks and HeLa cells are “just the skeleton” of Lacks’ story. Gilbert has spent her year at Radcliffe probing the ethical issues raised by Lacks and her HeLa cells to put flesh and form to those bones. Her work will culminate in an experimental documentary film titled “Colored Bodies: Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa Cells,” which Gilbert discussed at a Radcliffe Fellows’ Series colloquium June 20.

In 1996, Gilbert recalled, she was hard at work on her film “Homecoming … Sometimes I Am Haunted by Memories of Red Dirt and Clay” when she read an article in Emerge magazine about Henrietta Lacks. Intrigued but not wanting to shift her focus from “Homecoming,” a personal documentary about black farmers and land loss since the Civil War, Gilbert put the Emerge article in a box. “Homecoming” was broadcast on PBS in February 2000; several months later, Gilbert brought the box to Radcliffe.

“Colored Bodies” will go far beyond simply telling the story of an unsung heroine.

“I’m interested in the ethical – or not so ethical – relationship between Henrietta Lacks, her family, and Johns Hopkins University,” Gilbert said, noting that the Lacks story is a cautionary one with major implications today. Neither Henrietta nor the Lacks family gave permission for her cells to be used for research; in fact, the family didn’t learn about the proliferation of HeLa cells until the early 1970s. The Lacks family – still poor and struggling to access health care – has not been compensated for the use of Henrietta’s cells.

“For me, the real question is, ‘Do we as a society consent to the commercialization of the human body?’ For obvious reasons – I’m an African-American woman whose ancestors survived this country’s early participation in the trading, buying, and selling of human flesh – this question is of great concern to me,” she says.

Gilbert is drawn, also, to what she calls the “mythlike qualities” of Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa cells. In February 1951, just after Henrietta’s first diagnostic visit to Johns Hopkins, some of her tumor cells were sent to the lab of George and Margaret Gey, two Johns Hopkins researchers who had been searching for a line of human cells that would live indefinitely outside the body. Such cells, they said, would help them study cancer and possibly find a cure for the disease that killed Henrietta.

The Geys hit pay dirt with Henrietta’s cells, which multiplied in the lab with the same fortitude with which they ravaged her body with tumors. While David Lacks and his children were still mourning, George Gey was trumpeting his success, distributing the cells he dubbed “HeLa” to other researchers and, with his colleagues, using them in research that helped create the polio vaccine.

Here, Gilbert explains, the story turns a strange corner: By 1966, HeLa cells were so virulent that they had, unbeknownst to the scientists who used them, taken over other cell lines used in research. In 1974, California researcher Walter Nelson-Rees published a “blacklist” of research contaminated by HeLa cells, discrediting millions of dollars of research.

For Gilbert, the story of Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa cells provides fertile ground to plant creative seeds and generate discussion. “The idea of immortality struck me – that in itself is an amazing concept,” she said. “Here was a story that was historical, but also was contemporary. It’s a story that began in the past, but was continuing as I spoke and apparently had the ability to go on way past my own life span. It allows me to look at where were we in the ’50s around bioethics, where are we now, and what are the indications for where we will be 20, 30 years from now.”

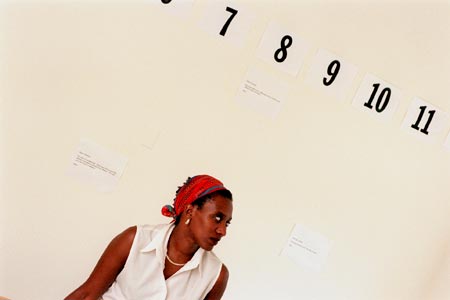

To give shape to “Colored Bodies,” Gilbert looked to her subject. “It became clear to me that the film, which is about the body, should take the form of the body,” she says. Gilbert will structure the film in 23 parts, like the 23 chromosomes of the human body. “Colored bodies” is the literal translation of the word “chromosome,” she explains.

Gilbert will explore Henrietta Lacks’ story and its ethical implications using a variety of storytelling tools, traditional and experimental. She plans to interview members of the Lacks family, including widower David Lacks Sr., who suffers from diabetes. She also hopes to interview scientists and experts, including contamination whistle-blower Walter Nelson-Rees, Johns Hopkins bioethicist Ruth Faden, a patent attorney, and religious and spiritual leaders.

Creating a less traditional narrative through the hour-plus film will be short notes to the filmmaker from a fictional writer named “Hela,” whom Gilbert describes as “a skeptical voice throughout the film.” Hela arose from Gilbert’s desire to explore ethics in her own field as well as medicine. “The documentary field also raises questions of consent, informed consent, and participation.”

“Colored Bodies” is very much from Gilbert’s point of view: “I make no claims to objectivity,” she says. In the last section of the film, she puts herself physically into the film as well, showcasing a series of X-rays and MRIs of her own body. “Oddly enough, in the 10 months that I’ve been here, I’ve had more interaction with the medical community than I’ve had in the last 20 years of my lifetime,” she says, explaining that she has had severe lower back and hip problems during her fellowship.

As she endured increasingly invasive tests, Gilbert says, “it began to strike me that looking at the images was useful to me in my work,” disturbing her and causing her to consider the boundaries of one’s body. “At what point do I no longer have claim or ownership over my body?” she asks.

As Gilbert finishes her Radcliffe fellowship and heads to Washington, D.C., where she’ll teach at American University and continue work on her film, she is unsure of the film’s final form or distribution. Acknowledging that its experimental nature might limit distribution, she says that she is committed to grassroots community screenings. Gilbert is passionate about generating discussion about bioethical issues.

“It’s an important story and I think that it raises all sorts of questions that are only now being dealt with in a public sphere,” she says. “The only way these questions get resolved is if we struggle around them, and discuss them, if we debate them and we argue them and come up with a public policy that reflects the will of the public and balances the concerns of all the parties involved. We can’t just be silent and hope that it will all work itself out.”