Roads scholar visits most remote spots

One week he dodged grizzly bears; another time it was an attack by raccoons; on yet another day he found evidence of wild bobcats inside the Chicago city limits. That all happened to Richard Forman as part of a project to visit the most remote areas in the contiguous United States.

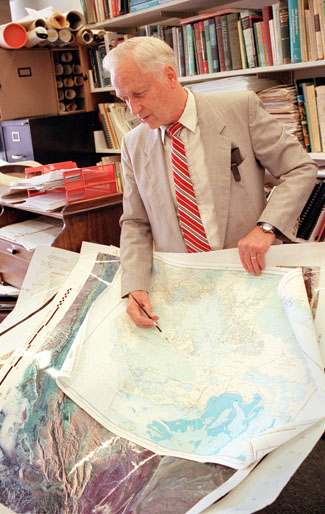

The Harvard University professor of landscape ecology tries to get as far as possible from roads so he can advise governments on where to close old ones and where to put new ones. He also tries to raise the consciousness of ecologists about road networks that crisscross every ecosystem.

“Roads affect much more than strips of land several yards wide,” Forman says. “They impact wildlife movement, biodiversity, vegetation, water quality, sedimentation of streams, and other natural things for miles around. Since there are 4 million miles of public roads in the U.S., used by at least 230 million vehicles, that’s a huge impact.”

How could he make this point to the public, Forman wondered. While traveling in Australia a few years ago, he got the idea of visiting remote areas, then telling people what it’s really like in places that are farthest from roads.

Forman started out in 1999 with a visit to the Teton Wilderness and Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. He and his adult son backpacked 70 miles in five days to reach what he believes is “the most remote spot in the western part of the lower 48 states.”

They mapped out a series of concentric rings that characterize the trail from road to remoteness. First, road noises disappear, then human and horse footprints. After that, you don’t see any beer cans, cigarette butts, or other trash. Wildlife tracks increase significantly, and plants not native to the area decrease.

Close to the most remote spot, 20 miles from the nearest road, Forman and his son encountered fresh paw prints and scat of a large timber wolf. Every hour while hiking for five days, they saw signs of grizzly bears, including footprints, hair on tree trunks, and logs that had been ripped apart.

You can’t run from a grizzly; it can cover the length of a football field in seven seconds. So, when Forman and his son saw fresh tracks, Forman quickly turned on his personally designed grizzly repellant, six wedge-shaped stones rattling around in a metal mess kit.

“It was not a relaxing trip,” Forman admits. “But you do experience a sense of exhilaration and a gut feeling of remoteness. Daily familiar things are gone. You feel that you’re in a place that’s much bigger than yourself, and beyond your control.”

Mapping road effects

Forman, who teaches at Harvard’s Design School and in the University’s environmental science and public policy program, doesn’t do these expeditions only for his own adventure. Several years ago, 20 years of experience researching the ecology of large regions got him appointed to a committee of the National Research Council charged with studying the future of transportation in the context of a sustainable environment. The group focused on emissions of greenhouse gases from vehicle exhausts. Forman saw an opportunity to focus as well on the effects of roads on everything from erosion and water quality to wildlife and vegetation.

His colleagues, Forman says, “found that idea to be like a breath of fresh air (pun intended).”

Forman’s road work was included in the committee’s final report, called “Toward a Sustainable Future” and published by the National Academy of Sciences in 1997. The experience spurred him to continue his research. He and 13 other leading ecologists, engineers, and policy-makers are preparing what Forman believes is the first book on road and vehicle impact, called “Road Ecology: Science and Solutions.” The book won’t be published until next year, but the research results will be presented at an international conference in September.

Forman has developed a concept he calls the “road effect zone,” to include the area over which a road exerts its ecological influence. He describes it as “bounded by a squiggly margin” on both sides of the road, which varies in width according to things like hills that block noise and streams that carry pollutants from roads.

Engineers look carefully at narrow strips on either side of a road. Landscape ecologists concern themselves with broad areas beyond these strips. “The road effect zone provides a common ground between these two perspectives,” Forman points out.

The upcoming book also discusses the science and technology that’s available today for designing such things as animal crossings. In Canada’s Banff National Park, underpasses, overpasses, and fences along part of the Trans-Canada Highway have reduced roadkill of deer, elk, and other animals by 96 percent.

In Florida, panthers, bears, deer, turkey, armadillos, raccoons, and even alligators use two dozen underpasses to cross Interstate 75, which runs east-west across the Everglades.

Researchers have learned that use of an underpass is influenced by its size and shape. Panthers prefer long, low passages; wolves and bears like high, wide tunnels. Deer avoid narrow arched passages.

Alligators, raccoons, and bobcats

For the most remote area in the eastern United States, Forman paddled into a mangrove swamp at the southern tip of the Everglades. “It’s the most extensive mangrove swamp in the Western Hemisphere,” he says.

In such places, trees and shrubs grow in the water, sending out dense thickets of roots that reach above the surface. Forman and three companions used a shallow draft sailboat and a canoe to maneuver through open patches of water and channels that lace the swamp. “I worried about thrashing alligators overturning our canoe,” he recalls.

Smaller animals gave the explorers more trouble than alligators, however. One night, while their sailboat sat on land exposed by low tide, raccoons attacked. “We chased them off, but they kept coming back,” Forman remembers. “They chewed through half of our plastic water jugs, and we were three days from civilization.”

Mosquitoes also turned out to be a problem. One morning, the travelers counted more than 500 of the bugs that they had slapped to death in their tents the night before.

The most remote spot lay 17 miles from the nearest road. However, the “sense” of remoteness didn’t coincide with that geographic point. One person felt the deepest remoteness during a long, quiet period without any vehicle, aircraft, or motorboat noise. For another, it occurred when a group of large porpoises exploded out of the water under a wooden platform where they were sleeping.

Forman felt the highest sense of remoteness when he clambered across intertwined mangrove roots and branches to a spot hundreds of yards from open water. “It was a place that a human footprint may never have fallen,” he thought.

To feel this sense and to reach the most remote areas, it’s not necessary to backpack into swamps or mountains. Forman found remoteness only a half-mile from a road in the southeast part of Chicago. Not far from a landfill, golf course, and automobile plant in the Lake Calumet area, he and two city land planners found fresh bobcat tracks and scat, coyote prints, a tree girdled by a beaver, snakes, rabbit droppings, egrets, heron, crayfish, and a pheasant feather.

Last March, he and two friends tramped through 2 feet of snow to the most remote spot in the historic town of Concord, Mass., which is a short drive from Boston. In two hours, they reached Thoreau Bog, where the great naturalist Henry Thoreau spent some time, and where Henry’s father once built a dam to get power for the family’s pencil factory.

Forman hopes that public consciousness about the ecological effects of roads will be raised by the information he collects and publishes about such places. The public, in turn, can influence what government agencies and Congress do to lessen the impact that humans have on these areas.

The Clinton administration placed a ban on new logging roads in some national forests, and the Forest Service wants to close some roads on federal land. There are good economic reasons for closing some of these roads. “More important,” Forman insists, “are ecological reasons. Human access must be limited if these key places and their inhabitants are to survive.”

“Our road system is already in place,” he continues. “New roads will be built mainly in urban fringe areas. They won’t involve a lot of miles, but they should not cut through remote areas, like the one we found in Chicago.”

Traffic on existing roads is increasing faster than population growth, and these roads are regularly maintained and sometimes widened. “Every time that’s done,” Forman points out, “an opportunity occurs to address issues like bird populations, biodiversity, water quality, and that essential sense of remoteness.”