Rowe’s secret garden

Construction crew’s find reveals a rich life

A new display, titled “WSR Discovers: Addie F. Rowe,” has been added to the Widener Stacks Renovation exhibition in the lobby of Widener Library. Inspired by a chance discovery in the recesses of Widener’s stacks, the exhibit offers a glimpse of a dedicated woman who spent a lifetime aiding scholars at Harvard.

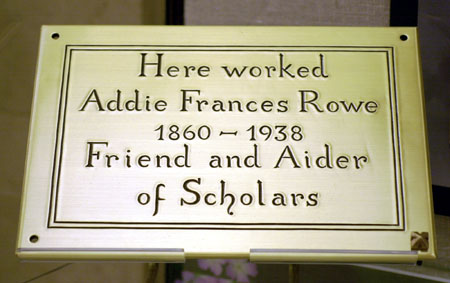

In August 2000, as part of the Widener Stacks Renovation project, a construction crew of the Lee Kennedy Co. demolished a wall on the east side of the Level 2 stacks. In the process, they found a memorial plaque mounted in a crevice inside the wall and inscribed simply: “Here worked Addie Frances Rowe, 1860-1938, Friend and Aider of Scholars.”

The tarnished bronze plaque was given to the Communications Office of Harvard College Library. A little research revealed the story of a simple yet immensely touching life, hidden in the records of the Harvard Archives.

Born in Canton, Mass., in October 1860, Addie Frances Rowe moved to Cambridge when she was only a year old and lived here until her death in 1938.

For 45 of her 78 years, Rowe worked at Harvard, devoting herself to preparing the books of University professors and visiting scholars for printing and publication. There is no official title or job description for what exactly she did, nor is it clear whether she was an employee of Harvard, or whether she was in fact paid by the book publishers. Probably the best description of her work is found in this preface to “The Influence of Milton on English Poetry” (1922), by her close friend Raymond D. Havens of Johns Hopkins University:

“Since 1916 Miss Rowe has devoted all her time to the book, bringing to it rare patience and thoroughness, together with experience in preparing manuscripts for publication. She has pointed out and helped to remove infelicities of expression, has called my attention to books I had not seen as well as Miltonic phrases I had not noticed, and in one way or another has improved every page.”

Rowe began her career at Harvard in the history department in 1896, proofreading and checking references for professors Channing and Hart’s “Guide to the Study of American History,” but later moved on to the English department. In August 1915, Rowe was the first nonfaculty person to be assigned a study carrel in the stacks of the newly finished Widener Library. With the approval of former director of the Harvard College Library Archibald Cary Coolidge, she moved into carrel 209 on the east side of the Level 2 stacks, where, for 23 years, she sat and pored over manuscripts for the books of various scholars.

Hyder E. Rollins of Harvard’s English department, whom Rowe called “one of my dearest friends,” was the man on whose manuscripts she worked most frequently. Together they saw 22 volumes through the press, and after Rowe’s death on Dec. 28, 1938, Rollins shared many memories of his friend in an introduction to “Addie Frances Rowe: An Autobiographical Sketch,” which she had written at his request.

“During her 23 years [in Widener],” he writes, “she became progressively more odd-looking. Style and dress meant nothing to her, as they are popularly supposed to mean nothing to all scholars. The quaintness of her ‘costumes,’ though it often caused smiles in a neighborhood where (according to the libels of outlanders) women are noted for their lack of style, would have attracted little, if any, attention in the British Museum.”

In addition to noting Rowe’s manner of dress, Rollins remarked in his writing that Rowe had another signature hallmark. From the time she first moved into the stacks, she kept an array of pink and red geraniums in her study carrel, a sight familiar to hundreds of people who never knew her name or her business. Over the years, her beloved flowers grew to unprecedented heights, as she herself described in the autobiography.

“In all this work done in this new library, I have had a garden in my window,” she writes in the autobiographical sketch, “which started with a small pink geranium from the florist’s given me in 1915 by Mr. Havens, who sat in the adjoining stall. Gradually a few more plants were added, and they all sat on the floor (as they do now!) and were small for a number of years, but finally those at the sides began to grow tall suddenly, reached the middle of the high windows, and kept on growing up. … I have cut off the top of the tallest plant (over 6 feet tall and in the same little pot it started in!) twice by a foot at least, else it would long ago have reached the top of the window and been blossoming in the next stall above.”

The Harvard University Press printed 55 copies of the autobiography – “merely a scrap,” as Rowe referred to it, most of which Rollins sent to her family and friends and to many of the scholars she had worked with. Today, three copies of the booklet remain at Harvard, one in the Harvard Depository, one at Houghton Library, and one in the Widener stacks.

In January 1939, following Rowe’s death and at the suggestion of Havens, Rollins wrote to Keyes D. Metcalf, librarian of Harvard College and director of the Harvard University Library from l937 to 1955. Rollins inquired about the possibility of putting up a plaque in memory of Rowe, and the library granted formal permission immediately. A few months later the bronze tablet was put up in the stacks, where it remained until its rediscovery.

Now, more than seven decades later, this exhibition offers a unique insight, through the eyes of those who knew “Miss Rowe,” into this woman who cultivated geraniums and scholars for 23 years.