Math As a Civil Rights Issue:

Working the Demand Side

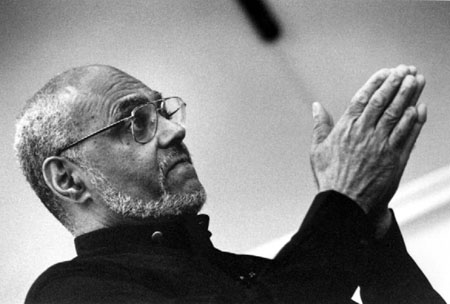

Robert Moses was a young man when he traveled from New York to Mississippi in the early 1960s. The voter registration movement he helped organize changed the political landscape of the South.

Twenty years later, Moses, as one parent in a Cambridge public school, started a project that would help African Americans advance in another arena with vast political consequences: education. Today, the Algebra Project serves more than 20,000 students in rural and urban schools around the country. A national network of schools and communities aim to create a self-sustaining movement for math literacy among students.

Moses spoke recently to an audience of young people and adults at the Ask-with Education Forum about his recent book, Radical Equations: Math Literacy and Civil Rights, about the connections between the past and the future, and about what gives him hope as an education activist. These are excerpts.

There are some young people here. I would like to talk to you, but I also need to talk to all these other people. Can we talk together, the young and the old? I want your understanding.

One of the things about doing the voter registration work in the 1960s is that when we would work with people, with sharecroppers, and they would come in and prepare to register to vote, it was more than just that. As soon as they made the decision and did that simple little thing-sit down in front of a piece of paper, take a pencil, answer a question-they were saying, in effect, I don’t want to be part of this system.

That’s what I think we do with the Algebra Project. We’re asking young people to step out into a different way of seeing themselves. And for me, it has the same impact as when I was working to register people to vote in the ’60s.

It’s not just about voting or just about math, but about the fact that black people in this country are part of a caste system. That generation after generation, black people have been assigned a certain place. And yes, the Civil Rights movement allowed certain black people to move into exalted positions. But as a whole, there’s still a caste system in this country, and it’s most noticeable in schools-in what I’m calling sharecropper schooling…a system where the expectation is that these people are only going to do a certain kind of work, and so they need only a certain kind of schooling.

Making the Demand

[Civil rights organizer] Ella Baker’s message is that the people who are oppressed by the system have to make a demand. You have to decide that you want to change. My sense from the Civil Rights movement is that this country doesn’t respond to make the kind of fundamental change required to break a caste system because someone is advocating it. We had civil rights organizations advocating for the right to vote; we had politicians advocating for the right to vote.

But there were people who didn’t want them to vote. And they said, “If they wanted to vote, they could vote.” So we got the sharecroppers to say, “Let us [vote].” And they stood by the hundreds at the polls. And that’s what changed the country.

The [kind of] argument that was used against the sharecroppers-“They were apathetic”-vanished as soon as the demand was made. As soon as the sharecroppers stood at the polls, the argument [about] apathy disappeared.

They say the same about kids in school: “The reason they don’t learn is that they don’t care.” But as soon as you’re out there making the demand, that argument disappears. This is the essence of what we’re trying to do, of how the Algebra Project is trying to work the demand side of education reform. How do we get young kids to demand what everyone says they don’t want?

We’re trying to get the young kids to make a demand, in a way they understand.

Math Literacy as a Civil Right

Computers have ushered us into a new technological age. Computers have brought us a new literacy. Fifty years from now people will say that people who can’t do math are illiterate. Computers have made elementary mathematics as important as reading and writing-for your literacy, your citizenship, your ability to have a job that supports a family.

The Algebra Project is trying to raise the issue of the floor around math education. What’s the floor for students in this country, so when they leave school they have a chance to function as citizens in this [world of] new technology?

In 1964, when the Civil Rights Act was passed, there was a provision to investigate the discrepancy between how black children and white children were educated in this country. They were shocked when the results came back that black kids, even in the Northeast, were doing worse in our educational system than the poorest white kids anywhere.

The answer was: we’re not going to fix the schools, we’re going to move the students. And so in Boston they bused students from the city to the suburbs, they set up magnet schools, charter schools; now we’re going to do vouchers. All of these programs [are about] figuring out the best way to shuffle the students around but not to fix the schools.

We have a discussion about sorting students-about who’s going to come to Harvard-but we don’t have a discussion about the floor. We have a discussion about the ceiling but not about the floor.

In our cities we have an educational system in which ‘pockets’ are given sharecropper education. People who graduate from these schools are not equipped to be citizens; they can’t get jobs that support families. So they hit the street and the street economy, and they get in the criminal justice system. We know it’s happening; we know it’s going to happen more.

Slowing Down

If you’re going to work the demand side, you have to slow down.

I started the Algebra Project in 1982. In the ’90s when the kids I was working with were in their 20s, some of them came down to work in Mississippi. They did something for the middle-school kids that I wasn’t able to do for them, which was to make it cool to stand up and do math. They’ve grown to a couple of hundred and consider themselves math literacy workers in Jackson, in schools, out of schools, in churches. They’re trying to wed math and fun, because the kids need to have fun. It took that amount of time to grow this, to have a generation come through.

A Life in Struggle

I think of my life as a life in struggle. I am able to think of it that way because I was mentored by people whose lives were completely devoted to struggle. They learned to live their lives in struggle in Mississippi. They gave a sense of what it looks and feels like to live a life in struggle. I think you can have a good life in this country in struggle. You can have friends, family, and a lot of the things that are important. You don’t have to be poor. You can. It’s a good option.