Master helps others harness ‘chi’ for health and healing

With a devoted following among students, staff, and faculty, and sworn testimonials of increased dexterity, relaxation, and balance of body and mind, the meditative practice of tai chi is a force to be reckoned with. So much in fact, that the Harvard Crimson selected classes in tai chi – which is said to foster the flow of a vital force (“chi”) throughout the body – as a top 100 “must-do” for Harvard students. Beginner tai chi student Rakhi Nandalal Mahbubani ’04 seems to agree. “My week doesn’t start until Thursday” she explains, referring to that day’s class.

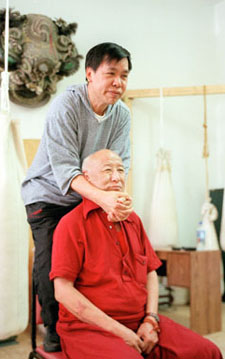

Yet even with the growing popularity of this ancient Chinese practice among the University’s community, Harvard’s chief tai chi and kung fu instructor – Master Yon Lee – a fourth generation disciple of the Tiger Crane Kung Fu style, is forever pushing this age-old art to greater levels of Western acceptance and utility.

“One of the things I wanted to do was separate the mysticism that surrounds it [tai chi],” explains Lee, who teaches beginner through advanced classes in tai chi, kung fu, and chi kung through the Harvard Health and Fitness program at the Malkin Athletic Center.

With his affable manner and contagious smile, Lee, who is also an Adams House senior common room associate, seems to have no problem imparting this idea – this demystification – to his students. Following a session of airy circles and slow stretches, Lee’s students, some of them seasoned practitioners, talk of regained strength from past injuries, corrected posture, and an enhanced sense of calmness. According to Lee, who is also the senior adviser to the Harvard Tai Chi Tiger Crane Club, the prescribed movements of tai chi and chi kung help one’s body to align itself, thus allowing the body to function at its optimum. “I believe that the human body has tremendous potential to heal itself,” Lee explains. “The movement of tai chi and its calming effect encourage body healing in an accelerated rate.”

For the academic Lee, a graduate of Brandeis University and the Graduate School of Physics at Northeastern, his efforts to have these healing practices – and their fundamental chi source – recognized by the medical and health care communities, go well beyond class instruction.

In 1984, Lee collaborated with a team of researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital to measure the effects of chi energy on cancer growth in mice. The “purely academic” research project proved to have some statistically significant results. The mice that received Lee’s chi energy treatment had a 10-day delay in tumor development versus the control group. Even more startling, Lee never actually touched the mice, which were kept in plastic containers throughout the study.

“We know it goes through plastic,” says Lee, taking chi’s healing properties for granted.

Lee looks to continue such bridge building between traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine. He is currently negotiating with Peking University about a similar research project involving diabetes patients. In addition, Lee spreads the word through speaking engagements at venues like Harvard Medical School and the Department of Athletics.

In the end, Lee is optimistic about the challenge of winning the endorsement of the Western medical community, seeing the “compatibility” problem as, essentially, one of communication rather than substance.

“Right now almost every software system that you want to sell you have to make a PC or Mac,” explains Lee. “In medicine it’s almost like the same thing – traditional medicine or Chinese?”

With unfettered enthusiasm and smarts to spare, one begins to suspect that a successful interface is on its way.