Experts say Mondrian’s rectangles not so square

Having a face-to-face encounter with a painting by the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) and looking at a reproduction are very different experiences.

Having a face-to-face encounter with a painting by the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) and looking at a reproduction are very different experiences.

To make this assertion about almost any other artist would be to state the obvious. Most people understand that the glowing tones of a Titian or the expressive impasto of a van Gogh can only be imperfectly hinted at in a print, and no art critic, with the possible exception of Sister Wendy, would suggest that looking at a reproduction is an adequate substitute for standing before the original work of art.

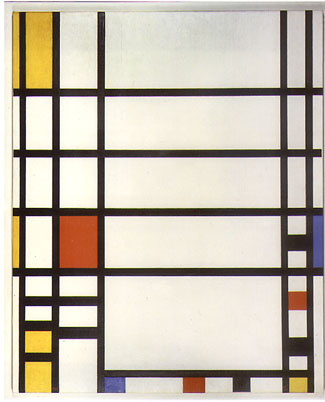

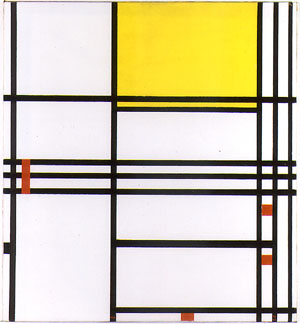

But with Mondrian, the realization comes as something of a surprise. The artist, at least in his later, most characteristic period, limited his palette to the primary colors – red, yellow, and blue – applied in rectangular patches over a white ground and delineated by perfectly straight black bands at right angles to one another. He arrived at this style, which he called “neoplasticism,” after years of experimentation with realism, symbolism, cubism, and others. The search seemed to refine his art down to absolute bare essentials, and with such simple visual elements to work with, it hardly seems that a reproduction would miss much.

But in fact it does. The 11 Mondrian canvases currently on display in the Busch-Reisinger Museum (“Mondrian: The Transatlantic Paintings”) seem to vibrate and sparkle with a mysterious energy. It has become commonplace for naive critics of the “my-5-year-old-can-do-better-than-that” school to dismiss Mondrian’s paintings as mere wallpaper, but the powerful presence of these works contradicts such a judgment.

Showing that Mondrian was a “painterly” painter rather than a graphic designer who happened to work in oils was one objective of the exhibition’s curators, Harry Cooper and Ron Spronk.

“Our main goal was to present Mondrian again as a painter,” said Spronk, associate curator for research at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. “These are real paintings, with a skin, and with weight to them.”

Cooper, associate curator of modern art at the Fogg Museum, added: “We wanted to show that they’re not just designs or diagrams of a higher reality.”

Cooper and Spronk, who have spent the past two and a half years conducting research on the paintings, planning the exhibition, and preparing the associated catalog and Web site, admit that theirs is not the only valid viewpoint. Influential critics including Clement Greenberg and Rosalind Krauss have emphasized Mondrian’s idealist side, his evocation of a world of pure mind whose relation to the paintings resembles that of Plato’s ideal forms to everyday reality.

In fact, Mondrian himself, through his own writings and lifestyle, gave credence to this interpretation. In an essay, he spoke of an “absolute harmony of straight lines and pure colors underlying the visible world.” In addition to which, he never showed the least interest in money, lived like a monk, and was a longtime member of the Theosophical Society.

But Cooper and Spronk have found abundant evidence to support their materialist view of Mondrian’s work. The works they examined, the “Transatlantic Paintings,” are paintings that Mondrian started (and in some cases finished) while he was living in Paris and London between 1935 and 1940. He took them with him when he left Europe to settle in New York City in 1940. There, responding to the impact of a new culture and new artistic influences, Mondrian extensively revised these works before exhibiting them in 1942.

He changed the arrangement of black lines, repainted the whites, and, most significantly, added bars of color without enclosing them in black. For an artist whose visual vocabulary was so limited, this was a very big step and anticipated his final New York paintings in which the black grid was eliminated entirely.

Mondrian told gallery owner Sidney Janis that the changes gave the paintings “more boogie-woogie.” Mondrian first heard boogie-woogie pianists Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons when he came to New York, and became an instant enthusiast, using the term in a number of later painting titles. He denied that his paintings were visual equivalents of the music, and yet one can see a correspondence between the rolling bass figures of this propulsive style and Mondrian’s black grids dancing with spots of color.

A raucous blues form originating in roadhouses and rent parties, boogie-woogie would not seem to be the kind of music a worshiper of ideal forms would be attracted to. Nor does Mondrian, a severe, angular figure wearing round, thick glasses and a three-piece suit (photos of the artist can be seen in the exhibition), conform to most people’s idea of a jazz fan. But in actuality, Mondrian maintained an intense interest in American jazz throughout most of his life. According to Cooper, he even took dancing lessons and kept up with all the latest steps.

But Cooper and Spronk’s strongest argument for supplanting the idealist view of Mondrian with a materialist view comes not from the artist’s musical tastes but from the laboratory.

Their examination of the paintings went far beyond the capacity of the naked eye, encompassing X-ray, ultraviolet, infrared, and microscopic photography. These techniques allowed them to penetrate beyond the surface of the paintings and to make deductions not only about Mondrian’s changes but also the order in which he made them. In many cases, the curators were able to compare their findings with photographs of the paintings in Mondrian’s Paris studio, thus adding a further dimension to the study. The results of their two and a half years of research fill 120 CDs.

Much of this data can be accessed through the exhibition Web site as well as at computer kiosks in the exhibition itself. The data has been programmed to allow viewers to see Mondrian’s successive changes as overlays and to jump from one to another by clicking the mouse.

What the research makes clear is that Mondrian’s method for reworking the paintings was intuitive and exploratory. He did not follow any preconceived mathematical principles but rather composed by eye, trying one change and then another.

If his only concern had been abstract design, then painting over his earlier work would have been an acceptable way of presenting new ideas, but this was not how Mondrian proceeded. Before adding a new area of color, he detached the canvas from the stretcher and laboriously scraped away the old paint in that spot, then built up the surface again.

“It was a quite physical, almost violent process of revision,” Cooper said.

Close-up photos of the paintings show not the smooth, featureless surface one might expect if Mondrian’s chief concern had been to convey a disembodied world of shapes, but a highly textured field of brushstrokes, some short, some long, angled in different directions as well as cross-hatched.

Mondrian’s interest in creating unique works of art is further shown by his practice of framing the paintings himself. Typically he did this by covering the edges of the canvas with a strip frame (he later used white tape for this purpose), giving the impression that the black grid lines continued around the edges of the canvas like ribbons around a box. Frequently, he then mounted the framed canvas on a larger board or subframe.

“You get the sense of a very taut surface held in place by black lines. It’s a neat, tight package under great pressure and control,” Spronk said.

Mondrian’s 11 neat, tight packages will be on display until July 22. The Web site is http://www.artmuseums.harvard.edu/mondrian. The site will be in operation for the next two years.