Surgery without scalpels:

Heat, cold, alcohol used to destroy tumors

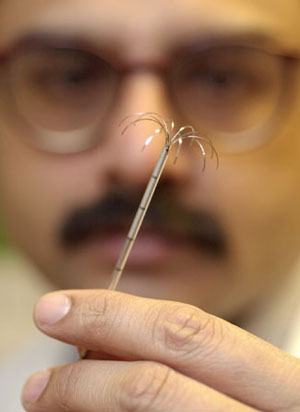

Rather than cut open a person’s chest or abdomen, doctors can now insert a slender needle through the skin and destroy a tumor with heat, cold, or alcohol.

Take the case of Paul Simmons, a 29-year-old Maine farmer who suffered with a lung tumor. On Feb. 18 at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, a probe containing a long needle was inserted into his chest and guided to the tumor by a scanning device. As Eric vanSonnenberg and his colleagues did the procedure, they could watch on a screen as the needle approached the lemon-size tumor in Simmons’ right lung. When contact was made, a burst of radio waves produced enough heat to literally “cook” the malignancy.

Simmons is impressed with the outcome. “I had an inoperable tumor; surgeons couldn’t reach it with their instruments,” he says. “In 20 minutes, it was gone. In three days, I was up and out of the hospital.”

Other hospitals in Boston and at various medical centers in the world are using the same technique with probes that freeze tumors or destroy them with alcohol. Such tumor killing is one technique in a new field known as “interventional radiology.” “It has become one of the fastest-growing areas of medicine in the United States,” according to Stuart Silverman, a radiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a member of the team that operated on Simmons.

Cardiologists use radiation to keep heart arteries open. A partially blocked coronary artery sent Vice President Dick Cheney to the hospital earlier this month. If the artery closes again, as physicians expect it will, this method would be one option they could employ to reopen it again.

To date, interventional radiology has been used to kill a variety of tumors, including liver, lung, kidney, bone, muscle, adrenal gland, and prostate. Different imaging techniques are also being investigated to guide the needle to its target. Simmons’ procedure was done with the help of computed tomography (CT) scanning. Radiology teams also work with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound imaging.

At the Brigham, radiologists are excited about the potential of a new type of MRI machine, a huge doughnut-shaped contraption that partly encloses both the patient and the physicians. “We’re using it to guide cryo (ultra cold) probes to liver and kidney tumors,” says Silverman. “You can actually see an ice ball grow to match the size of the tumor.”

A ball of destruction

William McMullen at the Harvard-affiliated Dana Farber Cancer Institute describes heat from radio-frequency probes as “a ball of destruction.” Cold, heat, and alcohol each have their advantages, and radiologists continue to discuss which to utilize under different circumstances.

“Cryo once required large probes,” notes Nahum Goldberg, a radiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. “You needed some surgery to get them in, but newer probes are small enough to be inserted directly through the skin.”

But the larger probes still have an advantage. “They make an ice ball that enables us to destroy a larger tumor and a small margin around it,” Silverman explains. The extra margin of kill decreases the risk of leaving malignant cells that can spread the cancer.

In Simmons’ case, heat did not destroy his entire tumor. About 20 percent of the malignancy remains and continues to cause what he describes as “wicked pain.” Radiologists plan to do a second procedure in hope of eliminating both the remaining tumor and the pain.

At present, most interventional radiologists use the radio technique. Another option involves a combination of heat and alcohol. “Adding alcohol helps the heat stay in the tumor area,” explains Goldberg.

Alcohol alone has been used on primary liver tumors at medical centers outside the United States.

Replacing conventional surgery with needlework was pioneered in Europe and Japan and at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. It has been used in this country mainly to destroy secondary tumors, resulting from the spread of cancer from other areas. Paul Simmons’ lung tumor spread from a primary cancer in his salivary gland.

Most procedures to date have been directed at tumors that spread from the colon to the liver. Such tumors may not be amenable to surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation. “Patients may be too sick to withstand surgery, or the tumor may lie in an area that can’t be reached by the surgeon,” Silverman points out.

Recently, however, radiologists have expanded their targets to include many types of primary tumors. “About 50 percent of our procedures are aimed at primary tumors, mostly in the liver,” notes Goldberg. “We have also used it as a bridge to liver transplants, that is, to rid a patient of tumors so he can survive until a new liver becomes available.”

“At Brigham, we’ve done 60-70 procedures, including tumors of the liver, lung, adrenal gland, bone, and muscle,” adds Silverman.

Researchers are looking into using interventional radiology for breast and prostate cancer patients, according to McMullen. VanSonnenberg, at Brigham and Dana Farber, says he has successfully done hundreds of cryo procedures in prostate patients.

“I’ve seen radiologists in Brussels and Vienna destroy prostate tumors with radio-frequency probes,” McMullen adds. “If I had prostate cancer, I’d go there tomorrow.”

One-stop shopping

Besides being easier on patients and requiring less hospital time, interventional radiology can be cheaper in many cases. That’s particularly true when the procedure is done on an outpatient basis. “At Beth Israel, we are now doing most of our interventions this way,” Goldberg notes.

A number of other treatments can be done without admitting patients to a hospital. Even before it was used to kill tumors, doctors employed interventional radiology to take biopsies (deep samples of tissues for analysis), drain abscesses, treat nerve pain, and remove stones from kidneys and gallbladders.

“Cancer patients have a wide variety of problems other than tumors that can be treated by this technique,” notes vanSonnenberg. “They may have an abscess in the chest or abdomen that needs to be drained, or blockages or stones in their kidneys, bile ducts, or gall bladders that need to be removed.”

“At Dana Farber, we want to have these services available to provide one-stop medical shopping for cancer patients,” McMullen adds.

For treating partly clogged coronary arteries, cardiologists insert a radiation probe into a thin catheter (hollow wire) that is threaded into the heart. In Vice President Cheney’s case, the catheter carried a balloon that was inflated to open the artery. Radiation can melt blockages away. Balloons push plaques against the walls of the artery, and in many cases the material grows back. Physicians say there’s a 50 percent chance that the treated vessel in Cheney’s heart will close again in three to six months.

For whatever purposes it is used, Silverman sees interventional radiology as “a burgeoning new field that has produced encouraging results so far.”