Light illuminates better teaching strategies

New book helps students get the most out of college

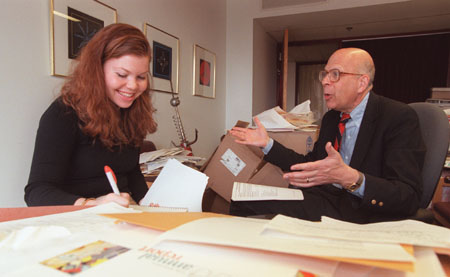

In 1986, Richard Light was asked a question that changed his life. He conducted more than 400 interviews and traveled to 90 college campuses seeking to answer it. Knowing that would not be enough, he enlisted dozens of colleagues and students to help gather data.

The question was “How can we assess the effectiveness of undergraduate teaching, advising, and quality of life?” Derek Bok, then Harvard’s president, asked the question, sending Light and his comrades on a 15-year mission of discovery. When Neil L. Rudenstine became Harvard president in 1991, he dramatically expanded the agenda, inviting Light to explore educational outcomes of racial and ethnic diversity on campus.

Light now has answers – answers that he expects will improve teaching and learning not just at Harvard, but at colleges across the country. On March 5, Harvard University Press released the result of Light’s quest, “Making the Most of College: Students Speak Their Minds.”

Light’s book questions – and in some cases flatly contradicts – much of the conventional wisdom about college teaching and how students learn best. It also makes a very strong case for diversity in student admissions at selective colleges and universities.

Most important, the evidence that Light cites in “Making the Most of College” comes directly from students, and not, as Light says, from “a bunch of middle-aged folks sitting at the Faculty Club who might not come up with these same ideas.”

Though Light, a professor at the Graduate School of Education and the Kennedy School of Government, is reluctant to use the word “customers” in relation to students, he believes that academia can learn something from business about tailoring products to the needs of consumers. “When students say something works, that’s powerful,” Light says.

The following are among the findings in “Making the Most of College”

- The widely held belief that colleges should admit talented students and then “get out of their way” is directly contrary to what students actually want; students report that some of their most meaningful college experiences involve those teachers and administrators who actively “get in their way” by offering advice, opportunities, and challenges.

- Students learn more when they study together in small groups outside of class than they do by studying alone, undermining the notion that such collaboration leads to “cheating.”

- Good advising is critical for most students, but many faculty who serve as advisers don’t pay as much attention to it as they should.

- Extracurricular activities and jobs do not detract from academic performance; instead, they increase students’ overall satisfaction with their college experience and contribute to learning.

- A very important thing for a student to learn is time management.

- Students are overwhelmingly positive about the value of racial and ethnic diversity, with white students being the most positive about it. Of 120 students that Light personally interviewed about this question, 111 readily offered examples of how they had learned from those of different racial and ethnic groups. Surprisingly, only about 20 percent of that learning occurred in the classroom, while 80 percent occurred in residence halls and while pursuing group activities such as rehearsals for theater or dance performances.Light hopes that high school and college students will read his book and pick up information that will help them to make the most of their academic careers. But he also has a lot of advice for professors.

Among Light’s suggestions

- Professors can better judge from week to week whether students understand the material if students write “one-minute papers” at the end of each class session. Light suggests that these papers simply summarize the main point of a lecture or discussion, raise any questions the student may have, and be anonymous, to relieve the pressure to perform that many students feel.

- Professors can do a great deal to improve learning by arranging students into outside-of-class study groups, and by dividing students into teams that tackle a particular side of a problem. Teams can then present their sides in class, generating discussion, debate, and learning.

- Students should present papers to their classroom peers, rather than simply submitting them to a professor, because they work harder and think more critically when their papers are for an audience of fellow students.

- Scheduling large classes just before meals helps generate outside-class conversations; students who live in the same dormitory and are taking the same class often leave the lecture hall talking and continue their discussion over a meal.Light has won many teaching prizes – Vanderbilt University recently recognized him as one of America’s great teachers, for instance – but he is something of an unlikely standard-bearer for pedagogical reform. His Ph.D. is not in education, but in statistics (Harvard ’69). Light joined the Harvard faculty on graduation, and his teaching for many years was devoted to statistics and educational evaluation, addressing questions such as “Does Head Start work?”Then came that call from Derek Bok in 1986. After a short discussion in which they realized that no one at Harvard was assessing the effectiveness of undergraduate teaching, Bok offered to put up some seed money and Light formed the Harvard Assessment Seminars. The idea was not just to offer suggestions for better teaching and advising, but to make sure those ideas were generated from solid data.Though it took the Harvard name, the Assessment Seminars from the start involved educators from many other institutions; the first meeting brought together 65 people from 25 colleges and universities. Eventually, Light also enlisted students to conduct interviews and interpret them.

To Light, those two strategies – drawing in experts from outside Harvard and employing a number of researchers, rather than just one or two – undergird the validity of his research findings, and their chances for being successfully reproduced at other colleges and universities.

“Most of the findings in this book would apply to other colleges, and some of them would apply big-time,” Light says. “As one colleague from Berkeley said, ‘If this works well at Harvard where you have so much for students, it should work even better at Berkeley where we have fewer resources.’ “

Light also cites the example of Bucks County Community College, near Philadelphia, which is very different from Harvard, but where professors readily accepted some suggestions that Light offered in a speech. “You know you’re on to something when they walk away saying, ‘This is great! I’m going to try this in my class next week,’ ” Light says.

So why haven’t the ideas in “Making the Most of College” been in wider circulation before now? Light offers two possible explanations. First, he says, faculty members simply haven’t asked students what they thought. And, second, he credits both Presidents Bok and Rudenstine with encouraging the project. “You need leadership,” Light says. “If the president says it’s important, then people will listen to that. I’ve been fortunate enough to have the strong support of two Harvard presidents.”

Rudenstine especially encouraged Light to look at diversity, which is covered in three of the book’s nine chapters. Students’ personal stories offer a rich testimony to the complexity of interactions among people of different races and ethnicities, and how learning comes from experiences that are positive and even from experiences that are difficult or awkward.

Now that “Making the Most of College” is in print, Light hopes that students and educators will read it and take its suggestions to heart.

Light will speak about his findings from 1 to 2:30 p.m. today, Thursday, March 8, at the Kennedy School’s Taubman Building, fifth floor, in the Allison Dining Room. The presentation is free and open to the public.