A Design School exhibit with an edge

Until a few days ago, yellow caution tape, the kind that might delineate a crime scene in a John Grisham novel – or perhaps an unavoidable Cambridge road project – was strung throughout the lobby of Gund Hall at the Harvard Design School. Metal rods hung low from the ceilings, and students scuffled around the obstacles, their senses on high alert in order to avoid injury. Since this lobby is a space that is forever in flux, it was not so unusual to find a crew working diligently at an installation. On most occasions, however, the chaos comes to a climax during this stage of the work, and a certain calm is restored when the exhibit is in place. Not this time.

A collaboration between four professors and 21 students at the Design School, as well as a complementary team from the Department of Music, has transformed this space into a moving and experiential exhibit, which takes a combination of static materials and explores their possibilities by combining, laminating, casting, and weaving them in new ways. At noontime, when traffic through the lobby climaxes, the exhibit “Immaterial/Ultramaterial” turns into a playground, and clusters of passersby stop to explore the auditory, olfactory, and tactile – as well as the visual – stimuli that surround them.

The exhibit, curated by Toshiko Mori, professor in practice of architecture, is organized around four themes with overlapping installations: “Surface,” “Substance,” “Edges and Corners,” and “Phenomena.” The collaborators who worked on these themes and supervised their design include Marco Steinberg, assistant professor of architecture; Nader Tehrani, assistant professor of architecture; and Ron Witte, assistant professor of architecture.

The faculty members on the project all have different interests, and for some observers, these differences make it difficult to see coherence across the installation. Still, as Mori suggests, these teams all worked under the scope of one vision: “The exhibition is designed to be experiential through its harnessing of physical space and materials, its exploration and celebration of the intense effects of immateriality, and its speculation about the coming era of ultramaterials.” Interestingly, these technically advanced (and potentially invincible) ultramaterials are often shaped out of the static materials of the past, and manipulated at the molecular level, where materiality is concealed or invisible.

“Surface,” which was designed by Steinberg’s project team, challenges traditional uses of humble materials such as homasote – a structural fiberboard made of recycled newspapers and used as roof or sidewall undersheathing. When saturated with water, homasote becomes quite pliable and can be shaped into fluid curves. This less explored property of the material interested the designers. “What have we not yet perceived in the commonplace materials surrounding us?” asks Steinberg. “The beauty of homasote is in its simplicity.” Steinberg also warns that the conflation of innovation and technology, which has shaped the architecture and building profession in recent years, is ultimately a reductive idea. “Immaterial/Ultramaterial,” he says, is an attempt to bring imagination back into the world of design.

While homasote, which has been manufactured by the same process since its inception in 1909, is a very common architectural material, the exhibit also features the uncommon. Explored in the cast-resin panels of “Substance” is a material known as aerogel. This silica-based stuff, which is “98 percent nothing,” is formed by suspending a low-density silica chemistry in a liquid solvent, and then extracting the solvent in an autoclave, leaving an ultra-fine glass matrix of hollow cavities. Aerogel was discovered in the 1930s and can be transparent, translucent, or opaque. NASA has used it in a variety of applications, such as collecting cosmic dust and insulating space vehicles. Its potential uses in architecture are almost entirely unexplored.

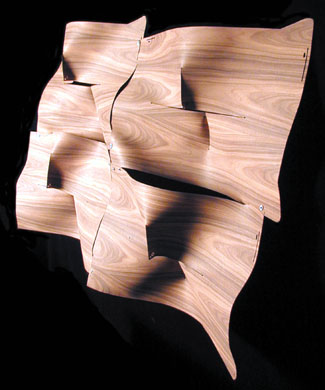

“Edge,” and “Phenomena,” the last two components of the exhibition, are equally engaging. “Edge” uses ancient techniques of tailoring to give shape and structure to thin and malleable materials such as plywood and rubber. As Nader Tehrani explains, the plywood membrane that braces against the ceiling, sags over the information desk, and wraps around a column is fabricated out of small units that introduce slits and enable compound curves.

Finally, “Phenomena,” which envelops the entire space, explores the role of the senses in architecture. Smell is evoked in a memory wall inspired by the Babylonians, who are known to have put perfume in their mortar. Meanwhile, sounds – ranging from the tinkle of bouncing aerogel, to the humming of traffic – are triggered by footsteps and heard through speaker cones that are attached to reverberating drywall.

“Immaterial/Ultramaterial” will remain open through April 7. It is just a small part of an initiative called “Millennium Matters,” which was conceived by Jorge Silvetti, chairman of the Design School’s Department of Architecture. This yearlong initiative is intended to provoke the public imagination, as well as present the breadth of scholarship and creativity at the school. The exhibit “Before and After the End of Time: Architecture and the Year 1000,” which was held in the fall at the Fogg Museum, also explored the materials, technology, and role of the architect – but focused on the first millennium. In addition to these two exhibits, the program of events includes lectures, seminars, roundtable discussions, design studios, and a symposium. A three-volume publication will accompany “Millennium Matters,” and an online version of the exhibit, as well as more information about the materials and installations, is available through the Design School Web site at http://www.gsd.harvard.edu.