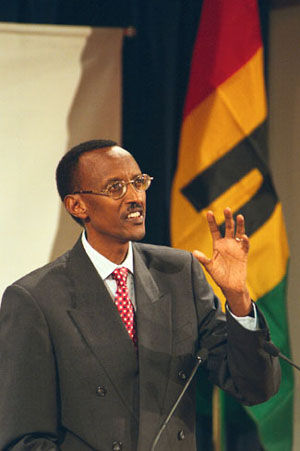

Rwandan president speaks at KSG

Rwandan President Paul Kagame says he wants an end to the conflict in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo, but not at any price.

With war in the Congo which has reportedly cost more than 1 million lives coming on the heels of Rwanda’s horrific 1994 genocide, Kagame admitted Monday that the continued conflict drains resources from the government’s goals of postgenocide stabilization and reconciliation.

But Kagame said Rwanda’s security comes before peace. He told a packed ARCO Forum audience at the John F. Kennedy School of Government that Rwanda is fighting in the Congo against the perpetrators of the genocide who, without military action, would resume raids across the border into Rwanda.

“Involvement in the conflict goes counter to the objectives of our government. … But in our case there are few alternatives,” Kagame said.

Rwanda and Kagame have come under fire for the country’s involvement in the Congo. They have been criticized for human rights abuses there and for allegations that some Rwandans are becoming rich through trade in Congolese timber and minerals.

The continuing war in the Congo was just one of a host of problems outlined by Kagame on Monday. Postgenocidal reconciliation is continuing, with perpetrators working side by side with victims and victims’ families. AIDS is ravaging the country, infecting as many as one in nine of the nation’s 8 million people. In addition, the criminal justice system is strained to the breaking point, with many thousands of alleged perpetrators of the genocide still in jail awaiting trial, six years after the massacres took place.

“It’s hard to think of a more challenging public policy problem or a greater challenge for a leader than pulling together a country after a genocide,” said Kennedy School Dean Joseph S. Nye Jr. in introducing Kagame.

The war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has defied easy answers. The situation is complex, involving troops from six nations and two separate rebel groups. On one side is the Congolese government, backed by Zimbabwe, Angola, and Namibia. Opposing them are two rebel groups, one backed by Rwanda and one backed by Uganda.

Caught in between are the Congolese people. The U.S.-based Human Rights Watch estimates that as many as 1.7 million civilians have died during the conflict from combat-related injuries, starvation, and inadequate health care.

The situation is dire enough for the U.S. State Department to provide $10 million in emergency aid. The money is intended to help an estimated 327,000 refugees and 2 million displaced people in the conflict.

Kagame headed the rebel army that captured Kigali, the Rwandan capital, in 1994. He was named Rwandan president in 1999, after the resignation of the former president, Pasteur Bizimungu.

Kagame’s family fled earlier episodes of violence in Rwanda, leaving him to grow up as a refugee in Uganda, where he served as an officer in the Ugandan army.

A bright light in the tiny African nation has been its women, who make up 54 percent of the population and head 47 percent of its families. Recent laws have recognized the crucial role women have played in the nation’s rebuilding, making it possible for women to inherit property from their fathers and husbands for the first time.

“Women have traditionally been sidelined in Rwandan political and economic endeavors,” Kagame said. “We fully recognize the critical roles women must play in our society.”

The role of Rwandan women in the nation’s rebuilding was what prompted Kagame’s visit to Harvard. It was sponsored by Women Waging Peace, an initiative of the Harvard Women and Public Policy Program.

“Getting to know the women of Rwanda has been life-changing for me,” said Swanee Hunt, director of the Women and Public Policy Program.

Hunt said instances of those on opposite sides of the genocide who are now working together are common. She described a visit to Rwanda where she came upon a group of women the wives of genocide victims and jailed perpetrators – who had joined together to create a granary called, “Let Us Console Each Other.”

“That demonstration of unity was profound for me,” Hunt said.

Kagame spoke for about 15 minutes and then fielded questions from the audience for almost an hour. Taiya Smith, a student at the Kennedy School, said she thought Kagame stuck to safe ground in answering pointed questions about Rwandan involvement in the Congo, but that the country is in a difficult position.

“Whenever he got into difficult territory, he came up with watered-down answers,” Smith said. “He’s made some mistakes, but certainly dealing with some of these problems is extraordinarily difficult.”