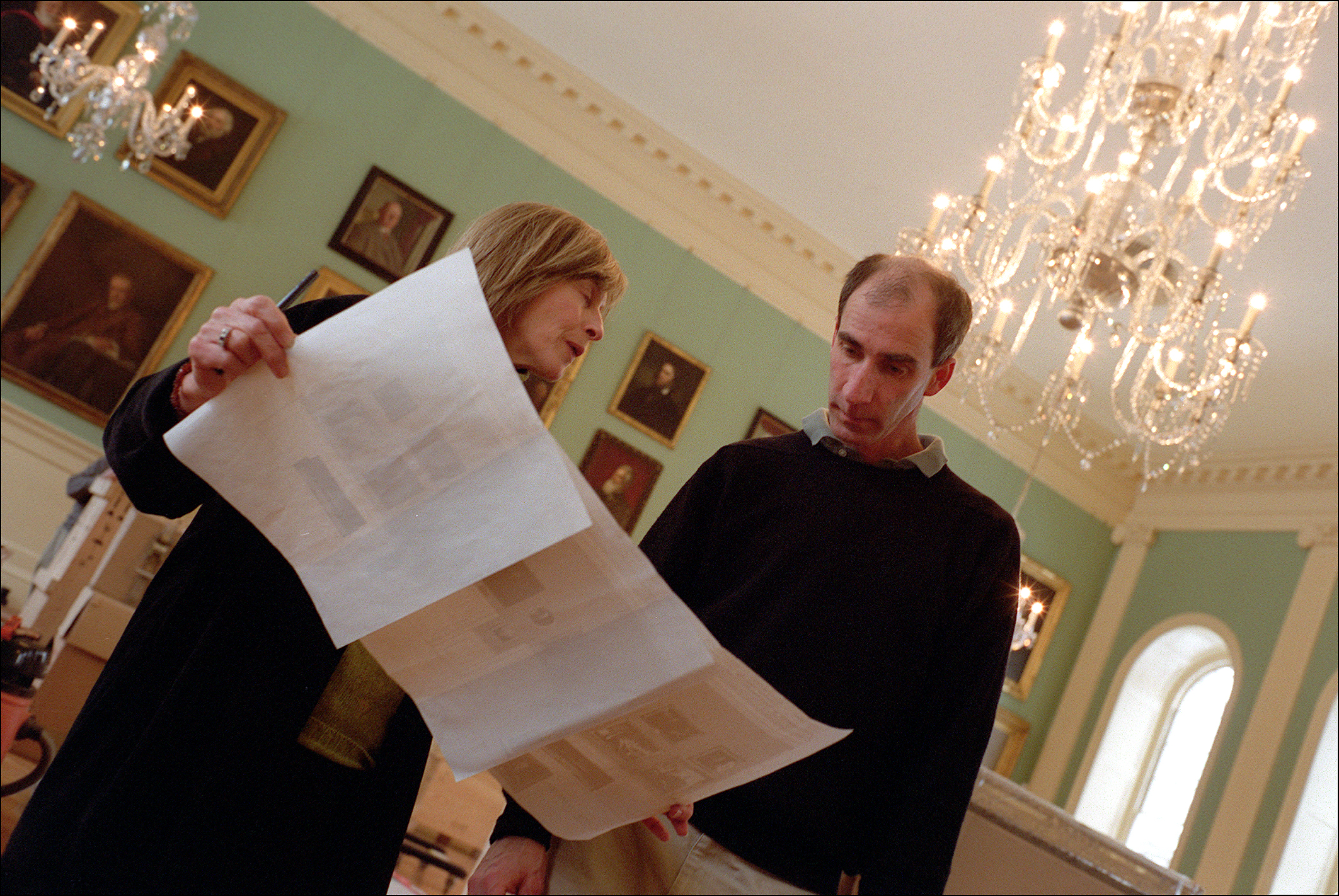

Sandy Grindlay of the Fogg Museum supervises the hanging of paintings and placement of sculptures in the newly renovated University Hall.

Photo by Justin Ide

History springs to life in restored Faculty Room

Functional, aesthetic, historically accurate restoration proves past is prologue

What’s old is new again.

In a labor of love, artistic discrimination, historical accuracy, and sheer muscular exertion, the Faculty Room in University Hall has been restored to something quite close to its appearance in 1896, when it first began functioning as the Faculty Room.

“It’s a glorious room,” says John Bailey, a member of Fine Arts Express, the company responsible for storing and then reinstalling the art in the Faculty Room.

The room originally served as the College Chapel when Charles Bulfinch, America’s first professional architect, designed University Hall in 1813. University Hall, a national historic landmark, housed kitchens on the ground floor, college dining rooms on the first floor, and classrooms and offices on the second and third floors.

In the late 1860s, the Chapel was radically divided; the upper half of the room served as an exam room, and the lower half split into two rooms: a classroom and a meeting place for faculty.

In 1896, during President Charles W. Eliot’s tenure, the space was restored to its original dimensions. One hundred and five years later, the room has been renovated in the spirit of both historical authenticity and modern aesthetics and functionality.

“The Faculty Room has regained a freshness and style that is both welcome and historically proper,” says Jeremy R. Knowles, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “Even the stern Eliot would be pleased, and Bulfinch would surely be proud.”

If the men (and woman) in the artwork could free themselves from canvas and stone and walk the Faculty Room again, they’d feel remarkably at home.

Paint analysts penetrated to sea-green walls dating to 1896, and a light tan trim. These colors have been restored, replacing light gray walls and an eggshell-blue ceiling. The floors have been refinished, and Oriental carpets, true to historic photographs, will replace the heavy red carpet formerly in use. The 12 arched windows, many of which contain old-fashioned crown-glass panes, have been retuned the putty fixed, the wood consolidated, weatherstripping and new chains added. The five chandeliers have been cleaned, rewired, and relamped. “They sparkle in the sun,” Bailey says.

Modern changes to the room, says project manager Elizabeth Randall, include two new doors and the installation of an updated heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system. A hidden audio system and security measures have been added as well.

Last Thursday, the room was a welter of wooden crates, plastic sheeting, cardboard boxes; a ladder here, a hydraulic lift there, a dolley, a gantry, a pallet jack to move the crated objects. In June, Sandy Grindlay, curator of the University portrait collection, oversaw the packing and storing of the 32 oil paintings and 15 busts, prior to a restoration process that would span the next seven months.

James Conant was flaking; Charles Eliot Norton needed to be cleaned. James Russell Lowell had a dent in his shoulder. Samuel Eliot Morison showed cracks.

“In the winter it was warm and dry in the room,” says Grindlay. “The wood shrinks, and the canvas and paint layer shrink. In the summer, it’s warm and moist, so the materials tend to expand. These fluctuations, between warm and moist and hot and dry, cause expansions and contractions, back and forth. Cracking and flaking are very damaging to paintings.” The new HVAC system will minimize fluctuations in the climate.

The antique hardwood frames, some with gilded and gessoed decoration, had suffered as well.

“People used to smoke in this room, and the frame conservator told me the frames were covered with an orange substance, which was probably nicotine,” Grindlay says. Fires formerly burned in the fireplace, adding grime.

The oil paintings range in origin from 1700 to 1996. John Singer Sargent’s portrait of President Abbott Lawrence Lowell holds pride of place over one of the doorways. The oldest portrait is of William Stoughton, presiding judge at the Salem witch trials. The newest, to appear in a year, will be Cecelia Payne-Gaposchkin, the first woman to receive a tenured post at Harvard. Every Harvard president for the past 200 years can be seen, in painting or bust, in every state of leadership: careworn, rallying, brooding, optimistic.

Ken Blye (left) and John Bailey of Fine Arts Express move a painting of President James Bryant Conant.

Photo by Justin Ide

Grindlay and her crew affixed new backing boards to the paintings, created new labels, and brought in new hanging hardware (1,000 feet of wire and 64 brass hooks). Five conservators from the Objects Lab of Harvard’s Straus Center for Conservation cleaned all the sculpture on site, mended minor cracks, and reduced discolorations. “It’s been constant work,” says Grindlay.

The curators of the Faculty Room Peter Gomes, Plummer Professor of Christian Morals; Bernard Bailyn, Adams University Professor, emeritus; and John Shearman, Adams University Professor worked closely with architects Bruner/Cott & Associates, Knowles, Grindlay, and Randall on the design plans for the room. John Fox, secretary of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, played a key role as well.

The effort shows.

As of this Monday, the paintings hung in banked triads, their gesso frames brilliant, their surfaces clear. Busts of Benjamin Franklin, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and others rose from stately columns, placed back near the walls. The leather-topped tables and benches had been moved into position, ready for use; two chandeliers, their lamps lit, brightened a room already flooded with natural light from the windows.

“There isn’t another room like it,” says Bailey. “The history of Harvard in one room.”