Mathematics is a game of life

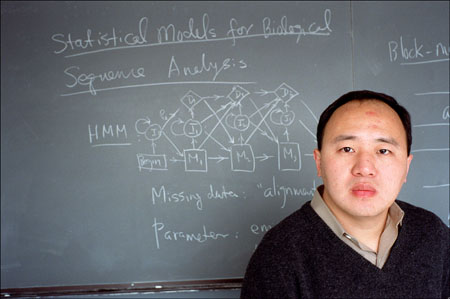

Jun Liu uses statistics to understand genes

Jun Liu remembers being interested in mathematics as early as age 12. It was a hard interest to pursue in the waning years of the Cultural Revolution in China. Computers were not available to him. He didn’t own a calculator. Mathematics books were difficult to find.

Jun’s parents, both teachers, scrounged books wherever they could. They borrowed books from older professors who had hidden them away. His father, a professor at a technical university in Beijing, copied one book entirely by hand.

“I couldn’t tell high school from college texts, so I read everything,” Liu recalls. “Doing math was like a game you could play with only a piece of paper and pencil. On Sundays, I rode my bike for an hour to meet friends and do problems.”

Sitting in his office at the Science Center, Liu, now 35, still shows a youthful enthusiasm for math problems. He wants to find answers to fundamental questions about genes and how they control life. “Every cell in your body contains a complete set of genes; each cell could become a part of your eye, your hand, or your brain. The question that challenges many scientists is how cells decide to be part of one organ or the other.”

Liu thinks he may be able to get some of the answers with statistics more quickly than biologists can with experiments.

Commenting on Liu’s recent tenure appointment, fellow professor of statistics Donald Rubin called him “a great asset to the University both as a teacher and a colleague. Harvard needs his strength in computational biology. In addition, he’s a wonderful warm guy, soft-spoken but with a fabulous sense of humor.”

Fooling around

Liu attended Beijing University, where he admits he spent most of his time playing bridge, and “fooling around.” Nevertheless, after graduation in 1985, he was among a group of top math students who came to the United States on a scholarship program supported by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

Sent to Rutgers University in New Jersey, Liu experienced cultural shock. “It was like a movie,” he recalls. “It didn’t feel real.”

Language turned out to be the highest barrier. “Fortunately, I could get by with understanding formulas and equations,” he says. “I got straight As without knowing much of what the teachers were saying. After a year, my English was worse than when I first came.”

In 1986, Liu transferred to the University of Chicago. While there, he became interested in human rights issues and spent a lot of time participating in student protests. That activism brought his adviser to ask him if he wanted to be “a politician or a mathematician.”

That was a turning point for Liu. He decided he had to apply himself to a career in statistics. “I didn’t want to solve problems just because they hadn’t been solved by others,” he says. “I wanted to connect to reality. Although I didn’t know exactly what statistics is, the field appealed to me for that reason.”

“Liu has very original ideas, exceptional ability, and amazing computational skills,” says Wing Wong, who supervised his Ph.D research in Chicago and who is now a professor of statistics at the Harvard School of Public Health. “He’s also a clear thinker who communicates his ideas well, and is an easygoing, warm, and helpful person.”

Tenure struggle

Liu earned a Ph.D. in statistics in 1991, then came to Harvard. During his first year, he met Wei Zhang, a graduate student studying immunology. They fell in love and married in 1994.

The same year, Stanford offered him a position in its statistics department. “I knew the chance of getting tenure at Stanford was nonexistent,” Liu says. “But the chance of getting it at Harvard was one magnitude less than that, so I went to the West Coast.”

His wife earned her Ph.D. in 1995, and followed him west. She got a job as a consultant in Los Angles and they commuted between apartments in the two different cities.

Despite his pessimism about tenure, Liu was offered the honor last year at both Stanford and Harvard.

The choice was not a difficult one for him. “I liked teaching undergraduate courses at Harvard; the students seemed more interested in the work than students at Stanford,” he says.

Liu is also impressed by “the many great biologists and chemists here.” Also of high interest to him is the new Bauer Center of Genomics Research where biologists, mathematicians, chemists, and others will work together to find the general principles that underlie life.

Liu now pursues the mystery of how genes are turned on and off. Using various statistical and computer techniques, he studies repetitive patterns in the DNA that lies between genes. This material contains instructions for regulating the expression of genes, and it is involved in whether the proteins produced by genes will become part of a brain or a big toe.

These on/off switches can be found by doing difficult, time-consuming experiments that require copying and mutating genes. If a region close to a gene is mutated and the gene stops producing a certain protein, that region must be part of a genetic switch. Liu believes he can locate such switches by statistical analysis of the genetic sequence patterns that occur between the actual genes.

Liu has done some of this work with collaborators at Harvard Medical School and the New York State Department of Health. For example, he has made about 2,000 predictions of where switches are located in the bacterium e-coli. In cases where these switches have actually been found by experiments, his predictions are 80 percent correct.

“What’s nice (or not so nice) about this field,” he says, “is that there’s always a judgment day. You are making predictions of actual happenings, so you’ll always know how right (or wrong) you are.”

Liu is pleased with his results so far. But humans have at least 10 times more genes than bacteria, so he knows that things will get a lot more complicated.

That’s OK with him. Talking with Liu in his office on a bright winter afternoon, it’s easy to see that he is glad to be here. He misses playing bridge, fooling around, and traveling as a student on a few dollars a day. And his wife, now a consultant, makes more money than he does. But Liu has tenure now, and it’s good to be back among attentive students and good colleagues. Best of all, he feels he can strengthen the contributions that Harvard makes to understanding what biological life is all about.