Defender of the clean, well-lighted place

Think of a space 33 percent larger than the Boston Common and the Public Garden combined. This is what New York City’s 503 privately owned public spaces would add up to if they were combined to form a single area.

Privately owned public space owes its existence to a zoning resolution enacted in 1961. New York allowed commercial and residential buildings to exceed normal zoning limits in exchange for providing plazas, arcades, walkways, and parks that would be accessible to the public. The most common formula was 10 square feet of rentable space for every square foot of street-level public space.

Other cities have adopted similar arrangements, notably Hartford, San Francisco, and Seattle. Boston has not followed suit, although public-private partnerships have been discussed.

On paper these zoning bonuses sounded like a win-win situation. Developers and landlords get additional revenue-producing property, and the public gets a plentiful supply of rejuvenating oases where they can read the paper, eat lunch, or just rest their weary feet.

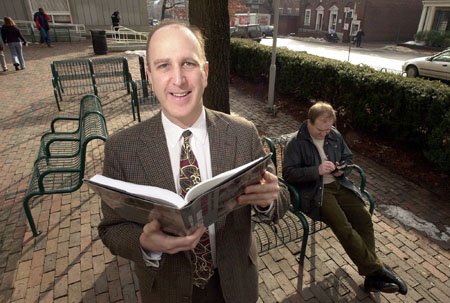

But how did the arrangement work in practice? Were building owners living up to their end of the bargain? Jerold Kayden, associate professor of urban planning in the Graduate School of Design (GSD), decided to find out.

The results of his study have been published in book form: “Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience” (John Wiley & Sons, 2000). The book is a carefully researched inquiry into the effects of law on the built environment, aimed primarily at urban planners, academics, and other design professionals. But it is also proving a powerful weapon in the hands of a put-upon public and has already helped launch the first volleys in what promises to be a new insurgency against encroaching commercial interests.

In addition to affecting public policy in New York City and elsewhere, the book’s findings were part of the discussion and decision-making surrounding state approval of mixed-use development in the South Boston Waterfront District Municipal Harbor Plan.

Kayden, who is both a lawyer and urban planner (he earned degrees simultaneously from the GSD and Harvard Law School), spent three and a half years on the project, which he undertook jointly with the New York City Department of City Planning and the Municipal Art Society of New York.

He estimates that he scrutinized thousands of legal documents – blueprints, permits, authorizations – scattered over several city agencies. Often crucial documents would turn up damaged or missing, resulting in ambiguities that could only be resolved through laborious detective work. He also visited all 503 spaces, took pictures, and interviewed users of the facilities. Kayden used several of his Harvard students as summer interns to help with the legwork, and collaborated with three urban planners from the city with whom he analyzed the data, but the task was still Herculean.

“It made the Florida recount seem easy,” he said.

According to Kayden’s findings, 41 percent of New York’s privately owned public spaces serve no public purpose, while 50 percent of all buildings with public space have a space that is out of compliance with legal requirements, resulting in some degree of privatization.

In some cases, the public is blatantly denied access, either by locked gates or officious doormen. In others, the space has been annexed or diminished by adjacent businesses, a phenomenon that Kayden calls “cafe creep,” “brasserie bulge,” and “trattoria trickle.” In still others, the amenities promised in the original contract – public seating, restrooms, trees – have not been provided.

Kayden ran into his share of altercations while conducting his research. In one public atrium used by an adjoining department store, he found the space filled with retail-oriented Christmas decorations. While he was documenting this infringement with his camera an official of the store stepped up and told him he wasn’t allowed to take photos.

“And you’re not allowed to have a department store in this space,” Kayden replied.

At another location, in which Kayden was using a cassette recorder to make notes, a guard told him that he was not allowed to speak into a tape recorder on the property.

Another finding of the study was a sharp qualitative difference between older spaces and those constructed after the mid-1970s, when the original zoning resolution was amended. The spaces constructed between 1961 and 1975 were minimal, often little more than a slab of concrete. The later spaces were more attractive and offered far more amenities, including adequate seating, drinking fountains, bike racks, landscaping, and decorative paving.

This dramatic upgrading shows that thoughtfully written laws can have a significant impact on the quality of the built environment, and that planners, designers, and lawyers have to be very careful in crafting law to assure positive outcomes, Kayden said.

But, as the record shows, putting laws on the books is not enough, even if they are good laws. In order to make public-private partnerships work, continued enforcement is essential.

“Ironically,” Kayden said, “more post-1975 spaces have been privatized by owners than the older spaces. The reason is that they were of such higher quality that they attracted more users, and the owners didn’t want the users there because they saw them as strangers invading their property.”

Kayden blames the privatization of public space not only on the owners, but on the absence of centralized records and periodic monitoring that should have been conducted by previous city administrations.

“To plan is human, to follow up, divine,” he said. “The focus is always on the initial creation of an amenity, but when there’s no follow-up, the provision of the amenity frequently falters. Five or 10 years later, it’s no longer being maintained, and no one is sure why.”

Kayden believes that his research project may help to facilitate better follow-up and thus help make owners of public spaces live up to their commitments. Kayden, the city, and the Municipal Art Society have produced an electronic database containing even more extensive legal and zoning information which should help with this ongoing effort.

The project has already generated results. Soon after the book came out, New York City brought three civil lawsuits and eight administrative actions against noncompliant owners. But Kayden believes that this is just the beginning.

“This is a first critical step. The subsequent challenge is to create a follow-up structure and an enforcement regime to make sure the public gets the benefits of the bargain.”

Though critics of big government might object to the added bureaucracy and expense, Kayden believes that there are compelling reasons for setting up an oversight structure to protect the public’s interests.

“There are some wonderful spaces in this inventory, which are of enormous value in a densely packed urban center like New York City.”

Not only do these spaces provide relief from the hustle and bustle of the city streets. They also provide a setting for the kind of planned and unplanned encounters that give the urban experience its unique value.

“The marvelous thing about cities is that, unlike suburbs, they are bulwarks against the privatization tendencies of society. People of all income levels and social backgrounds are forced to converge in the public realm. Everybody sees everybody else, and even if some of the encounters are unpleasant, it helps to guarantee the realism of life, to make sure we see difference and learn to value diversity. If we allow our public spaces to be privatized, we have suffered a self-inflicted wound.”

Contact Ken Gewertz at ken_gewertz@harvard.edu