De Klerk has a ‘clear conscience’

Former South African President Frederik Willem de Klerk made a case for international protection of minority groups to a receptive but sometimes skeptical audience that questioned his role in the abuses of South Africa’s discarded apartheid past.

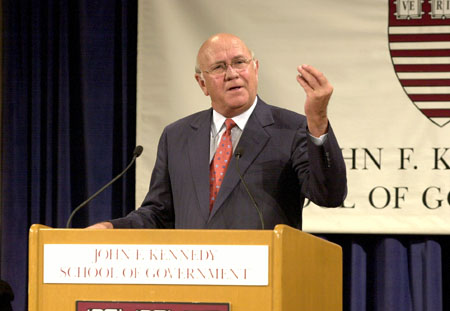

De Klerk, who shared the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize with his one-time opponent and successor as president, Nelson Mandela, spoke Feb. 7 at the John F. Kennedy School of Government’s ARCO Forum before a packed house.

De Klerk told the audience that the nature of the wars waged around the world today has changed. Instead of disputes between nations, which marked many 20th century conflicts, fighting today tends to be inside a nation, between different ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural groups.

The spread of democracy, combined with the lack of protections for minority groups, has concentrated national power in the hands of many countries’ majority groups. Often, that situation has meant marginalization of minority groups’ culture, language, and tradition. That marginalization builds hatred and can lead to wars of extraordinary brutality, featuring ethnic cleansing, massacres, and genocide, which de Klerk described as “a rolling holocaust presenting enormous challenges to people across the world.”

He cited a variety of recent conflicts as examples – from the wars resulting from the breakup of the former Yugoslavia to conflicts in Indonesia to the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

“Let us tackle the problem of world peace by going to the root cause for the lack of world peace. It is in many instances the tyranny of the majority. It is the alienation of important minority groups. It is suppression of specific languages and cultures,” de Klerk said. “We need to come to grips with the management and accommodation of diversity in a just and equitable way.”

The speech was sponsored by the Council of Women World Leaders, an independent, international organization based at the Kennedy School. The group includes current and former female government leaders. Former Canadian Prime Minister Kim Campbell introduced de Klerk, crediting his reforms – including ordering Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 and ending the ban on the African National Congress – with South Africa’s peaceful transition into a post-apartheid democracy.

“This is an extraordinary man, an extraordinary leader, and one of the architects of the history of our time,” Campbell said.

The industrialized West has not experienced many of the problems plaguing developing countries because political parties often have ideological, rather than racial or ethnic, foundations, de Klerk said. Western democracies are not immune to such strife, however, as Spain’s Basque separatists and conflicts between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland illustrate.

All minorities, not just disadvantaged minorities, should be extended protections, de Klerk said. Privileged minorities, such as the whites in South Africa, shouldn’t be discriminated against, he said. Today South Africa is experiencing white flight because many whites view the government’s affirmative action policies as discriminatory. The result, de Klerk said, is that the nation is losing many skilled people who could be helpful in its rebuilding.

He called for international standards and conventions that would ensure that ethnic, racial, linguistic, and religious minorities’ rights are protected. Those groups, he said, should be ensured freedom to practice their culture and traditions and should be ensured a voice in government, particularly on issues that affect their communities. In addition, their children should be given the chance to learn from teachers speaking their native tongue whenever possible.

“The prospect of permanent exclusion from power is a stark reality for ethnic minorities across the world today,” de Klerk said.

De Klerk’s speech drew a partial standing ovation from the crowd, but he also drew some hard questions about his role in South Africa’s apartheid system. De Klerk answered questions about his role as education minister in the country’s segregated education system, a post he held from 1984 to 1989. De Klerk acknowledged he did not attempt to integrate the schools, but insisted he did attempt to reform them by beginning to equalize spending on schools serving blacks and whites.

A question about his role in atrocities committed by government security forces drew a denial that he had any role in killing opposition leaders.

“It was never the policy – and I never was part of a policy decision where any indication was given – that it would be OK to commit cold-blooded murder,” de Klerk said. “This is one thing, between me and my god, on which I have a clear conscience.”

Several in the audience expressed mixed feelings about de Klerk, saying his words struck the right note, but doubts about his past made them wary.

“If it was someone else speaking I’d be inspired, but with him I’m suspicious,” said Krista Donahue, a first-year Kennedy School student.

Donahue compared de Klerk with former Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev. The reason both men were able to engineer peaceful transitions from discredited systems of government to new democracies, she said, was that they had been part of the old system.

“It was very moving, but it is difficult to know the truth,” Donahue said.