Teaching medicine Western-style

SPH student to help establish medical school in Nepal

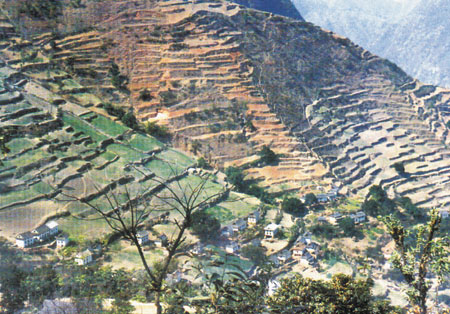

When School of Public Health (SPH) doctoral student Mark Hickman goes to medical school in September, he will not be commuting. He is flying off to the green farming terraces of the village of Dhulakiel in Nepal where, on a swath of land jutting from the side of a Himalayan mountain, engineers are laboring in the thin air to erect a building that may revolutionize medical education in Nepal. The building will be a medical school organized by Nepalese officials with the help of Harvard professors.

And Hickman is not going there to learn medicine, but instead to help establish the first Western-style medical school in the country. He will teach basic science to a new generation of Nepalese doctors.

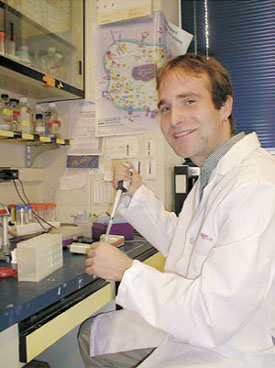

Hickman, 26, was working on his thesis in the laboratory of Leona Samson, professor in the Department of Cancer Cell Biology, last fall when he received an e-mail that would change his life. The message was from Harvard Medical School (HMS) Professor Cliff Tabin inviting him and other specialists in biomedicine at SPH and HMS to learn more about temporary teaching opportunities at a yet-to-be-established medical school in Nepal. Hickman was intrigued.

“I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do next in life, and this sounded like a unique chance to interact with people from another country and gain new experiences,” said Hickman.

The school is the brainchild of a Nepalese physician, Arjun Karki, who received his training in the United States. One night over dinner with an American ophthalmologist friend, Karki expressed his desire to create a Western-style medical curriculum in Nepal. The ophthalmologist piped up that his brother was a professor at Harvard Medical School and could help him. Soon after, Cliff Tabin received an e-mail from Karki.

Tabin was surprised, but he was also interested — and energized. He sent out a call for volunteers and received about 40 responses. From those, a core group of 15 SPH and HMS members have committed themselves to traveling to Nepal next fall and teaching basic science classes in blocks of six, 12, or 15 weeks. The effort is, indeed, a volunteer one. The travelers’ airfare and room and board will be paid for, but they will receive nothing else in finances. The rewards are purely personal.

“One would hope to expect this kind of response,” said Tabin. “We have so many resources and a responsibility to give back to the world. This is an opportunity to have a large impact on the health of a group of people.”

There are currently seven private medical schools and just under 900 doctors in Nepal. Some of the doctors received their training in India and China and, rarely, the United States, but many attended Nepalese medical schools where the quality of education is poor, said Tabin.

He explained that curricula are often dated and taught by retired faculty members who may be unemployable elsewhere. And, in a country with a per capita annual income of $200, medical education is very expensive, said Tabin. Only a privileged class can afford to attend. One of the goals of the new school’s organizers is to make the price of medical education more reasonable while dramatically increasing the quality.

Despite the high cost of training doctors in Nepal, the need for more of them is painfully apparent. Infant mortality rates run at 83 deaths per 1,000 births, and those infants who do survive face a 63 percent risk of being chronically malnourished before they reach the age of 3. Approximately 20,000 new cases of tuberculosis are diagnosed each year. The average life expectancy is 57 years.

The medical school will be run under the auspices of Kathmandu University, 30 miles away, and will be called Kathmandu University Medical School. Officials expect to accept about 40 students in the first year. Similar to the education system in England, these students will attend the school fresh from high school.

“It will be an experience getting there and figuring out where they are in terms of their knowledge,” said Hickman. “If I see them looking at me with blank stares, I’ll know that I have to slow down.”

A jazz piano hobbyist, Hickman said he’s not afraid to improvise. That notwithstanding, a lot of thought and effort has been put into deciding how best to teach students who are trained from an early age not to ask questions of their teachers; queries are considered disrespectful. Organizers have decided that a problem-based, case-study approach would work best, with students attending a lecture each day and then discussing how to approach specific cases.

Hickman has worked as a tutor and teaching assistant before, but he has never taught a full course himself. To bolster his knowledge, he has been practicing with an HMS medical instructor and has been sitting in on lectures that reflect the teaching style he will use in Nepal. Hickman engages in all of this while continuing to conduct lab research for his thesis, but he says the hard work is worth the opportunity to help put together a medical school curriculum from scratch.

“We are hoping and working to make the school well established and respected,” said Hickman.

The school’s organizers have applied for grants, but money and supplies are still needed (the SPH and HMS teachers will bring many of the classroom and laboratory supplies with them).

To learn about how to donate used textbooks, microscopes, slides, and other equipment, contact Mark Hickman at (617) 797-1544 or mhickman@hsph.harvard.edu.