A picture’s worth 1,000 prejudices

Fogg exhibit of Middle East travel images shows politics behind postcards

It is a standard albumen print, labeled “Palmyre, Sculpture d’un chapiteau, Syrie,” and signed in the lower right by the Bonfils studio. The caption refers to the capital of a fallen column that dominates the foreground, and locates it at a tourist site in Palmyra, Syria. Except for a child apparently sleeping on the capital, dwarfed by its deeply carved acanthus leaves, the scene is barren.

This deliberately composed photograph is one of innumerable images that were snatched up by Western audiences as surrogates for travel in the Middle East. During the 19th century, when photography was still believed to be a transparent medium – more real than any painting – images like this were mass marketed to a public that could not afford to visit the ancient sites.

To Jülide Aker, however, there is much more to the story. Aker argues that “audiences of the time would have recognized in the once-lofty capital an implicit metaphor for the decline of the civilization that erected it, while the sleeping boy would have figured as a reflection on the state of the current inhabitants of the Middle East.”

The Bonfils photograph is one of more than 80 works exhibited at the Fogg Museum in “Sightseeing: Photography of the Middle East and Its Audiences, 1840-1940,” open through April 22. The exhibit documents the ways in which 19th century photography mediated Western audiences’ encounters with the East. It was curated by Aker, an Andrew W. Mellon intern at the Department of Photographs in the Fogg Museum, and Ph.D. candidate in history of art and architecture.

At left, in an albumen print made by the Bonfils Family, the image of a sleeping child, is dark with veiled messages. The Bonfils’ print, at right, served to ridicule the rituals of Islamic prayer.

At left, in an albumen print made by the Bonfils Family, the image of a sleeping child, is dark with veiled messages. The Bonfils’ print, at right, served to ridicule the rituals of Islamic prayer.

The notion that 19th century photographs depicted the Middle East as a historical or mythological land, populated by lazy, promiscuous, and primitive people, is not new to the field of Middle Eastern studies. These images, many scholars contend, were part of a pervasive Orientalist discourse, which sometimes aided colonialist projects by providing a visual vindication of Western superiority and rationalizing the occupation of the East.

The exhibit, however, is the first to illustrate this discourse through photographs, images that would otherwise be languishing in basements at the Harvard and Boston Public libraries. It exemplifies the effective use of the Harvard Art Museums, whose mission is to preserve and exhibit art, but also complement scholarship and research.

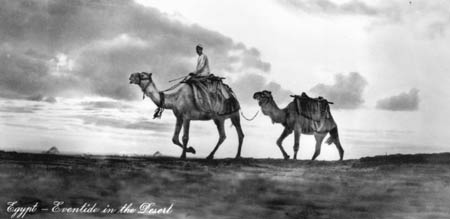

A vast collection of images, including salt prints, albumen prints, stereo views, illustrated Bibles, albums of snapshots, and postcards or cartes de visite, have been drawn together in this critical survey of 19th century sightseeing. Albumen prints such as the c. 1920 Lehnert & Landrock image of Bedouin nomads on camels, and the c. 1885-90 Bonfils photograph of an octopus fisherman near Mt. Carmel, depict locals, sometimes with great intimacy. The Bonfils fisherman, for example, stands barefoot at the end of a long path, while the spotted tentacles of his octopus stretch to the ground. The image looks so real that viewers will be tempted to reach out and touch.

In fact, however, many of these images were elaborately staged. As Aker notes, in at least one book containing early daguerreotypes, the photographer admitted that stock items such as galloping riders, camels, tents, and pipe smokers were purposely inserted into the compositions.

The staged portrait, “Turkish Sheikh Praying,” belongs to a popular genre of Muslims at prayer. In the guide that accompanies the exhibit, Aker writes, “Everything that was deemed perverse about Islam was distilled in Western reactions to Islamic prayer (what Mark Twain called ‘gymnastics’), which was seen as too ridiculous and grotesque to qualify as proper worship.” By positioning the viewer in place of the God to whom the figure would be bending to worship, the photographer not only shows lack of respect for indigenous people, but also the presumption of Western viewers in their relationship to these Eastern subjects. Aker notes that the old man’s apparent compliance only reinforces this presumption.

Religion played an important discursive role in the reception of photographs, since the vision of most travelers to the Holy Land was filtered through the Bible. “Every spot and stone in Palestine that might have had even the most tendentious connection to the Bible was photographed,” Aker observes. The title of one book on display speaks volumes about the expectations of travelers: “Evidence of the Truth of the Christian Religion: derived from the literal fulfillment of prophecy, particularly illustrated by the history of the Jews and by the discoveries of recent travelers.”

The search for religio-historical verification can also be seen in salt prints by Auguste Salzmann, who photographed architectural remains in Jerusalem in order to settle a controversy about the existence of pre-Roman and Solomonic remains. The project was an archaeological inquiry, but the debate it hoped to settle went to the heart of colonialist questions about ownership of land. In the 19th century, as today, the tug-of-war for Jerusalem was framed in terms of precedence and history of occupancy.

Although many photographers, such as Salzmann, positioned their images within continuing conversations about the Middle East, as photographic techniques improved, they also produced them as sheer spectacle. Lantern slides, which were projected to 30 feet by 25 feet in full color, became a popular mode of presentation.

More people experienced views of the Middle East through stereoscopes than through any other format. In the 1880s, Underwood & Underwood started producing table-top and hand-held stereo viewers and double-image stereo views. Together these provided illustrated Sunday school lessons and popular parlor amusements. In the stereo view of a pyramid, which can be seen in the exhibit, the camera is placed at the base, giving the impression of a summit that is impossible to reach. These stereo views provided viewers with a near-tangible experience of the terrain, and were advertised as “The Short Cut from Home to Holy Land.”

Like countless other items in the “Sightseeing” exhibit, they are definitely worth seeing.