‘Stag’ faces changing times

Thomas Derrah doesn’t look much like a king. Wearing a Hawaiian shirt and baseball cap, he sits scrunched up in a front-row seat at the Loeb Drama Center, scribbling notes on a yellow pad.

Thomas Derrah doesn’t look much like a king. Wearing a Hawaiian shirt and baseball cap, he sits scrunched up in a front-row seat at the Loeb Drama Center, scribbling notes on a yellow pad.

And yet, for the past decade and a half, Derrah has been a most convincing king — King Deramo of Serendippo, who marries his true love, Angela, only to have her, his kingdom, and his life nearly stolen by the scheming minister Tartaglia.

Deramo, Angela, and Tartaglia are characters in “The King Stag,” one of the most successful productions ever staged by Harvard’s American Repertory Theatre (ART). First produced in 1984, the play has charmed audiences throughout the United States and in Spain, Italy, Japan, Taiwan, and Russia.

Now “The King Stag” is gearing up for another tour, but there is a difference. For the first time, nearly all the parts in this fable by 18th century Venetian writer Carlo Gozzi will be played by a new set of actors.

In a play where much of the dramatic effect depends on carefully staged, stylized movement, the transition can be a bit worrisome, like passing a treasured family heirloom on to the next generation. Will the youngsters appreciate it and care for it as their elders have done? Will they keep it alive?

Derrah has been doing his best to see that the play survives, working with Jay Boyer, his successor, and the rest of the cast as a movement coach and guardian of the production’s elusive soul.

“No one has ever played the role of Deramo but me,” Derrah says. “His movement is based on Balinese dance. It’s highly choreographed and more complicated than the other parts. It was taught to me by Julie Taymor, and then I embellished it and made it my own. Now I’m passing it along to Jay, and he’ll bring another quality to it and make it his own.”

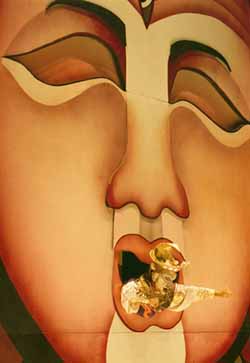

Julie Taymor has since gained fame for her staging of “The Lion King” on Broadway. In 1984, as a relatively little-known theatrical designer, she worked with director Andrei Serban to bring this forgotten commedia dell’arte piece to new life. Drawing on the traditions of Balinese dance, Kabuki, Noh drama, Peking opera, Bunraku puppet theatre, and others, she created the costumes, sets, and choreography that make the play so visually arresting.

One of her innovations was the use of puppets — birds swirled through the air on fishing poles, leaping stags as delicate and weightless as clouds, a huge, billowing bear, and an emaciated old man who rises from the dead animated by King Deramo’s spirit. The puppets are manipulated by cast members dressed from head to foot in blue — the “blue people” in the play’s backstage jargon.

“The blue people help tie the show together by moving in and out of the scenes. But they’re also invisible. We forget they’re there,” says Kelli Edwards, a veteran of the show who calls herself “the wrangler of the blue people.”

The monochromatic costumes help establish that invisibility, but Edwards is convinced there is something more enigmatic at work.

“I believe that as they begin to focus their performance energy into the puppet, they disappear. But it takes a while to get to that point.”

In Bunraku, the ancient Japanese puppet theatre, on which Taymor’s creations are partially based, students take years to achieve mastery. Edwards has three weeks to teach her blue people to operate the puppets.

“The first week we’re building up strength. There are a lot of muscles we’re not used to using. The second week we’re putting in all the details, and the third week we’re getting it all to gel.”

One of the most remarkable things about “King Stag” is that it uses stylization and artifice to tell a story packed with human emotion. Wearing masks forces the actors to discover a whole new vocabulary for conveying the characters’ inner life.

“You have to keep the mask alive,” Derrah says. “It’s a special technique of creating expression by the movement of the head and neck. It takes a lot of working in front of the mirror.”

Kristine Goto, one of only two actors who have appeared in previous productions of the play, says that the style also requires a kind of manic focus and energy.

“I think there’s a piece in all of us that’s the kernel of the character we play, and we need to make that kernel explode so it fills the stage. You have to commit to the performance 100 percent. If you only half do it, it’s ridiculous.”

Goto plays Clarice. Her father, Tartaglia, wants her to forget her lover, Leandro, and marry the king, but, true to her feelings, she proves incapable of deception or disloyalty.

“She’s not the brightest puppet, but she’s as naive and pure good as you can get. It’s a fun role.”

Kevin Bergen, who is new to the play, found that learning his character, Truffaldino, required a sort of creative submission to the traditions and conventions that had preceded him. Like most of the play’s dramatis personae, Truffaldino is a stock character who appeared in innumerable incarnations during the heyday of commedia dell’arte, a semi-improvised theatrical tradition that flourished in Italy from the 16th through the 18th centuries.

“Tommy Derrah gave me the basic movement vocabulary for Truffaldino. He described him as a bird with clipped wings. I played with that image, and Tommy would reinforce me or steer me in a different direction until I came up with stuff that was my own and fit in with the part.”

Each actor must struggle with the problem of finding a personal, creative response to the theatrical traditions behind his or her character. Abbie Katz must deal with that problem for the play as a whole. Katz was stage manager of the 1984 production. Now she is the play’s remounter, making sure that the production turns out just like the original, but without being a lifeless copy.

“The show has to be the same, but the actors have to bring something new to their roles or else they’ll be bored and the show won’t grow.”

Interviewed when the play was in its last week of rehearsal, Katz was cautiously optimistic.

“I don’t think it will be bad, but you just don’t know until you do it in front of an audience. The truth is, it’s a beautiful show. But it can be really great or just nice.”

Kristine Goto is less reserved.

“This piece has everything that makes the theatre magical. I mean, here we are, a bunch of actors with papier-mâché masks on our heads. It wouldn’t work anywhere else but in front of an audience. They have to help us make something happen, and they do.”

“The King Stag” will be performed in the Loeb Drama Center until Sept. 28. For ticket information, please call (617) 547-8300, or visit the ART Web site at http://www.amrep.org.