Before (and after) the end of time

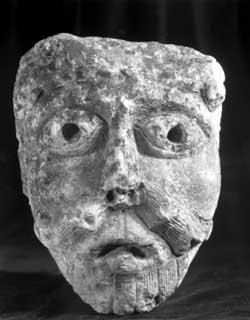

Christine Smith points to a small limestone capital, a fragment of a French medieval abbey. It is mounted high on the wall of an exhibition room at the Fogg Museum. Below it, a white stripe connecting it with the floor suggests in a subtle, minimalist way that the pocked, weatherworn carving is resting on the ghost of a column.

“That’s the look I wanted in this show,” she says. “I wanted it to be spare, thin, almost astringent, dematerialized.”

Smith, the Robert C. and Marian K. Weinberg Professor of Architectural History in the Graduate School of Design (GSD) has been planning this exhibition for the past two years. Titled “Before and After the End of Time: Architecture and the Year 1000,” it grows out of a course she teaches of the same name.

The exhibition is not about objects, she emphasizes, but ideas — materiality and immateriality, time and timelessness.

Focusing on the millennial year 1000, it explores two historical developments which at first glance seem difficult to reconcile. One was the widespread belief that the world was about to be swept into oblivion and replaced by the mystical and apocalyptic Heavenly Jerusalem. The other was the advent of the massive and very permanent architectural style known as Romanesque.

And yet, in the medieval mind, the juxtaposition of a ponderous building style with a belief in the impermanence of earthly life did not necessarily imply a contradiction. In fact, the identification of the material church with the immaterial kingdom of God on earth was affirmed each time a church was consecrated.

“When you walk into one of these churches, you are in the Heavenly Jerusalem,” Smith says.

That identification was also embodied in the geometry underlying the buildings’ massive stone structure.

“The purity of the geometry is evident in the layout and the elevation of the buildings,” says Smith. “It’s one of the most striking qualities of Romanesque churches, and I believe it contributes to the sense of serenity that characterizes their atmosphere.”

But how does one create a museum exhibition that is essentially about abstractions, and yet make it visually interesting?

The answer that Smith and her collaborators came up with is to give the exhibition an experiential dimension — to make viewers feel that they are stepping back into the mental and imaginative world of medieval times.

Designed by Assistant Professor of Architecture Marco Steinberg, the exhibition clothes its abstractions in an artfully arranged skein of drawings, engravings, photographs, gemstones, and sculptural fragments.

In addition to the capital on its ghostly column, there are other architectural pieces placed so as to approximate the position they would have had in an actual building. It is a little like entering a pencil sketch of a church with only a few of the details filled in.

Entering the exhibition, visitors walk under a corbel in the shape of a cow whose position is much the same as it would have been in its original location. Two elaborately carved stone capitals from 12th century French churches face one another across the main room, sitting above eye level on tall plinths. The apostles Mattias, Jude, and Simon, carved back to back in the shape of a column, form an axis with Kenneth J. Conant’s delicate drawing of the tympanum at Cluny III (last and largest of three abbeys to occupy this site) and an illuminated case containing a schematic representation of the Heavenly Jerusalem.

“We tried to display the artifacts in relative position to one another in such a way as to convey the scale of the structures,” says Steinberg. “There are little symmetries and asymmetries. Things aren’t just equal, but relate in a more complex way.”

The lighted case, designed and built by Steinberg, is the exhibition’s centerpiece, literally and figuratively. Here, glowing in the center of the darkened room, is a two-dimensional depiction of something that is closer to an idea than a place, the spiritual city with its twelve jeweled gates. Steinberg’s bejeweled schematic is based on a 10th century manuscript known as the Morgan Beatus.

Supplied by Carl Francis, associate curator of the Mineralogical Museum, and by the House of Onyx, twelve gems sparkle mysteriously in the up light of Steinberg’s magic box.

One of the challenges, Smith says, was identifying the gems as they are described in the Latin Vulgate, the bible of western medieval Europe. For example, jasper is “iaspis,” lapis lazuli is “sapphyrus,” and emerald is “smaragdus.”

Smith decided to used faceted gems for this display to enhance the visual effect, although the technology for this type of gem-cutting did not develop until much later. Color photos of the same gems, but rough-cut in the medieval style, appear on the wall.

Smith emphasizes the collaborative nature of the exhibition. Others who have contributed, in addition to Francis and Steinberg, are James Ackerman, the Arthur Kingsley Porter Professor of Fine Arts Emeritus; Marjorie Cohn, the Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints, Fogg Art Museum; and Hunter Tura, a recent GSD graduate in architecture.

Ackerman was largely responsible for the first sections of the exhibition, which present the contributions of three pioneers in the study of medieval architecture, all with Harvard connections: Henry Hobson Richardson, a Harvard graduate who became one of the foremost architects of the 19th century; Arthur Kingsley Porter, who taught at Harvard in the early 20th century; and Kenneth J. Conant, trained as an architect at Harvard and later Porter’s successor as professor of art history.

These sections include Conant’s exquisitely detailed drawings of Cluny, the abbey in eastern France that was a great religious center during the Middle Ages. Through his archaeological research, Conant reconstructed the three churches that occupied the site, culminating in Cluny III, which, in its day, was the largest in the world. It was destroyed during the French Revolution.

Smith was surprised and delighted to find these drawings in Harvard’s collection.

“I had studied them before, but not in the original. When I found them in the Loeb Library’s Special Collections, I was just amazed. They’re very special.”

Another very special series of works that occupies an important place in the exhibition is Odilon Redon’s lithographic illustrations from the Book of Revelations. The lithographs are owned by the Fogg.

Redon (1840-1916), whose work is often seen as a precursor to modernism, can hardly be considered a medieval artist, but Smith decided to include him because his lithographs give powerful expression to the biblical prophesies of the end of time.

“I think they fit in because they’re without time-specific details, and they have a strange, dreamlike quality that is consistent with the tone of the show.”