Defining genocide: Allan Ryan uses his legal knowledge to find ways to classify terror

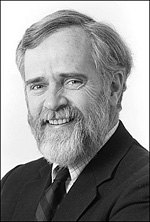

Gray-bearded and slightly rumpled, Allan Ryan peers over the top of his reading glasses. He has just been thrown the question of whether personal passion is what drives his interest in the prosecution of war criminals and human rights offenders.

There is a long pause, a lawyerly pause, perhaps. Ryan is, after all, an attorney in Harvard’s Office of General Counsel as well as the instructor of a Summer School course called War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice.

“I’m wary of calling it passion, because there’s enough passion on this subject to go around. What I’m trying to say is, look, how can we make this thing work? Yes, we’re all outraged at what’s happening, but how do you structure a program of trials? What do you do with the right to counsel? What do you do with the selection of judges? What do you do about coming up with a definition of crimes? Let’s see if we can make this thing work, and by doing that serve in some way the cause of justice. That’s passion enough for me.”

Ryan’s interest in the subject comes from personal experience. From 1980 to 1983 he served as director of the Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, building cases against Nazi war criminals living in the United States. The interest has remained strong, occasionally involving him as a participant in international issues, most recently as an adviser to the Rwandan government in 1995 on how to prosecute those responsible for the genocide that took place in that country.

The search for accountability

In teaching the course, now in its fourth year, Ryan resists turning it into a discussion of his own experiences prosecuting war criminals. But he does find that his legal background is a valuable asset in helping him to structure the material.

“I’m not a historian, I’m not a Ph.D. All of this stuff I basically picked up on the fly. But I think that being a prosecutor really does provide a perspective that helps make this material bearable to work with.”

Historian or not, Ryan is clearly fascinated by humanity’s efforts to bring some sort of accountability and order to the savagery of armed conflict. He traces these efforts back through the Nuremberg Trials of 1948, to The Hague and the Geneva Conventions of the late 19th century, to the writings of Hugo Grotius, the 17th century authority on international law, all the way back to the knights of the Middle Ages and the lawgivers of ancient Rome.

One of the high points of the course is a screening of Shakespeare’s Henry V, the Kenneth Branagh version, a play that Ryan believes sums up much of what we now accept as the law of war.

“Students are fascinated, I think, to find out just how much we know as the law of war today was completely developed and understood in Shakespeare’s time.”

Defining the unthinkable

But fascinating as it may be to delve into the remote past, Ryan admits that the most vital issues have to do, not with rules about what is and what is not permissible on the battlefield, but rather with crimes against civilian populations, a subject that has held center stage since the Nuremberg Trials attempted to deal with atrocities committed by the Nazis.

“The really rapidly developing law today is in this question of what constitutes genocide, what constitutes crimes against humanity? How can we devise effective judicial procedures for enforcing that law? So when I call the course War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice, it really is an attempt to look at those three elements. Is it possible to address them? Is there really any such thing as justice when you’re talking about 6 million people who were killed because of their faith?”

Horrible as these crimes are, Ryan insists on the need to devise strict, clear-cut, legal definitions of what constitutes genocide, for without such definitions, attempts to prosecute criminals are often stymied.

Lacking these definitions, Ryan said, the situation can too easily become politicized. This is what happened in 1994 when the U.S. State Department “bent over backwards” not to call the massacres in Rwanda what they in fact were.

“Why not call it genocide? Easy. We didn’t want to do anything about it. You can’t say, ‘Yeah, well it’s genocide, but we don’t care.’ If you’re not going to do anything about it, you’ve got to call it something else.”

Assigning strict parameters to the crime of genocide, to talk of numbers killed and other specific issues, may seem cold-blooded, but such definition is necessary to avoid the sort of prevarication that kept the United States and other nations from acting in the case of Rwanda.

Hostage to politics

“What’s happened is that the definition has become hostage to the political decision of what to do about it, and I think that’s backwards. I think you’ve got to have some way of deciding what is and is not genocide, and then base your decisions on that. Does that sound like a typical ivory tower, pointy-headed approach? Maybe it does. But from a legal point of view, how can you charge somebody with a crime unless you’ve got some definition of what that crime is?”

Ryan realizes that for most people, legal definitions are not the most compelling aspect of genocide. Rather, it is the question of evil that grabs the average person’s attention when contemplating scenes of carnage in such places as Germany, Cambodia, Rwanda, and Kosovo. But it is just such psychological or philosophical questions that Ryan avoids dwelling on in his class, not because they do not interest him, but because their enormity overflows the boundaries of his legal expertise.

“One of the common reactions of anyone, including the students, after reading about the Holocaust, is to say, ‘How could people do these things?’ And my answer is, I wish I knew. I don’t know any more than the next person what would enable a man to wake up in the morning and kiss his wife and play with his kids and then go off and operate a death camp until 6 o’clock at night and then go home and sit down and have dinner.”

Perhaps more important than understanding the nature of evil in an abstract way is the necessity of dealing with it, of devising principles and procedures that allow legal authorities to address such outbreaks of savagery and, through the application of justice, restore a sense of order.

And what the experiences of the 20th century have shown is that a crucial aspect of such proceedings is often not so much punishing the wrongdoers, whose crimes may in fact be so heinous as to be beyond punishment, but to allow the victims to have their say.

“It’s becoming recognized and accepted that without some effort to bring closure to these crimes, they continue to fester,” says Ryan.

“The strongest motivation I have seen in survivors is not hatred or revenge. It’s disclosure. They want the world to know what happened. Unless there is some attempt to have accountability, the victims will feel that their injury continues, that the crime continues, that the cover-up continues … that there has been no acknowledgment of their suffering.”