Woody wows film students

If Woody Allen had been directing the scene, chances are he wouldnt have left any of it on the cutting room floor.

The legendary actor/director/comedian cracked a few jokes, told a few stories, and dispensed several nuggets of valuable advice as he answered questions from Harvard film students last week during an appearance at Loews Harvard Square Cinema, sponsored by the Harvard Film Archive and DreamWorks Pictures.

It was the fourth and final stop in Allens latest college tour, coinciding with the release of his latest film, Small Time Crooks.

While the film itself got mixed reviews after Wednesdays screening, Allens performance got the thumbs up from many in attendance. As one student said later, “he was terrific charming and entertaining.”

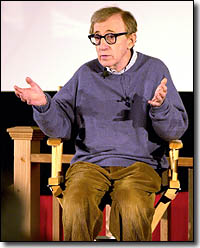

Wearing a blue sweater and tan corduroy slacks, Allen appeared as relaxed and unassuming in real life as in the movies, sitting in a directors chair alongside Boston Globe film critic Jay Carr, who acted as emcee. Allen fielded an array of queries from the bizarre to the philosophical as he recounted his childhood in Brooklyn, his early professional years as a writer, and his tremendous success on the big screen.

“When I grew up, I wanted only to be a playwright. I had no interest in doing anything else,” Allen explained. “I didnt want to be in the movies. I didnt want to work in television, or be a comedian. None of those things ever occurred to me. I wanted to be a playwright, and I wanted to be a serious playwright. Im really a frustrated 1930s playwright.

“I started writing for television in hopes of earning a living, while also trying to write plays,” he said. “The first shock I got was that I could write comedy, and that I wasnt going to be Eugene ONeill. Then the theater started changing. [It] became less serious and more frivolous. Films, influenced by some great, great foreign movies, pushed aside all the trivial films of Hollywood, and it suddenly became apparent that one could make good films. So I started getting more interested in the movies.”

In 1965, Allen was hired to write the script for Whats Up Pussycat. It was a big hit but he doesnt take credit for it. “They took my script and mutilated it,” he told the Harvard audience, “and it was a really successful movie, which really doubled the pain for me. I hated it.”

As much as Allen hated the film, the success of Whats Up Pussycat catapulted his career onto the fast track. “I vowed that I would never work in the movies again unless I could be the director of the film,” he explained. That opportunity came in 1969, when Allen was asked to direct Take the Money and Run. It was the first in a series of slapstick comedies that established Allens wacky style and steady box-office appeal.

“I was very lucky,” he told the film students of his early success. “I had a track record of being a sensible person. People [in Hollywood] felt I was not a raving lunatic who would take their money and run.” It is a character trait that has served Allen well ever since. “I never had any egregious, catastrophic failures financially,” he said. “Ive had failures, but no Heavens Gate. I never bankrupted the studio. My films are made for comparably inexpensive budgets, so nobody really gets hurt when they dont do well.”

Allen also stars in many of his films, but he claims thats not intentional. “I have a very limited acting range,” he said. “When I finish [writing] a film, if theres a role I can play in it, I play it. If there isnt, there isnt. I dont really care about being in my films. It doesnt really matter to me.”

What he does care about, Allen says, is guiding the film along as it develops, from the idea to the script to the finished product, no matter how trying the circumstances.

“You will often enter a project with grandiose ideas,” he said. “Youre convinced that this is the script thats going to go down in history, and after 10 weeks of shooting, you edit what you have together, and suddenly it becomes a desperate struggle for survival. Youre willing to sell out and do anything to make the script work because all your courage leaves you in the face of putting the film before the public and suffering a catastrophic humiliation.”

There havent been many of those in Allens career, although he admits that many of his more cerebral movies, like September and Another Woman have played to limited audiences. “I tried to make some serious films over the years with marginal success. I would say that most people hate my serious films, but I enjoy making them.”

Allens advice for Harvard film students trying to make it in the industry is to allow themselves every possible opportunity to achieve success. “Theres no [set] procedure to follow,” he told the audience. “He or she who has the talent, if that person gives it enough time, it will emerge, and reality will weed out those who dont have the talent. I know that when youre young, its very hard to know [whether or not youre going to succeed]. Thats why you have to give it a fair shot.

“After a number of years of trying, youll find that reality will make the decision for you. Somehow [the good ones] find ways to make it.”

Sage advice from someone who has.