Scoring the Future — Arts Medalist Harbison wants budding careers to bloom

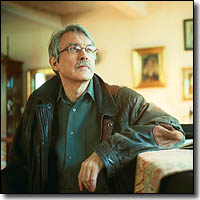

His lifes work is a montage of musical masterpieces, including three symphonies, three string quartets, two operas, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning cantata “The Flight into Egypt.” Yet, its not so much the creation of the music as the drive to preserve its audience into the future that drives composer John Harbison 60, this years Harvard Arts Medal winner.

Harbison is immersed in the effort to develop a new generation of concert music lovers. Having been raised in an era when there was a “much ridiculed, but very effective music appreciation wave in schools, colleges, and on the radio,” the Cambridge-based composer is worried that during the past 20 years or so, “we [as a society] have given up” on the opportunity to expose young people to the arts.

“If you dont at least offer that experience, I think youre cheating a huge number of people,” Harbison says. “Virtually every child in this country needs to, at least, have certain kinds of moments pass by them to see whether theyre candidates [to enter the musical realm].”

Its for that reason that Harbison counts himself as a supporter of ARTS FIRST, Harvards annual arts celebration marking its eighth year with a four-day weekend festival beginning Thursday, May 4. “Im a fan of programs that dont give any whiff that the arts are unreachable or elite. They are elite, of course, because they choose their own constituency by their nature, but how can those choices be made unless the exposure is broad?”

Establishing a Musical Beachhead

Following his 1960 Harvard graduation, Harbison went overseas to study music. After receiving a masters degree from Princeton University in 1962, he returned to Harvard as a junior fellow. In 1970, he began teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.) where he is currently the chamber music coach.

Instituting a music program at M.I.T. has been a challenge, according to Harbison. “Its been an effort to annex some territory, to get a beachhead, and move in, and thats been part of the fun because you start with just a little piece of land, and you try to get a little more.” The effort is now beginning to pay off. “We have a lot bigger part of the terrain now than anyone ever thought we would,” Harbison says. “Theres a tremendous awareness that what is most useful to graduates competitively are all the things that the core doesnt provide. At that really crucial competitive point is where Stravinsky and Mozart come into play.”

While humanities and social science programs date back only 50 years at M.I.T., they are considered much more ingrained in the long-standing academic culture at Harvard. “Its good that Harvard has a lot going on in terms of making people aware of the arts in the world,” Harbison says. “Thats something thats built into the structure [of the University].” Yet Harbison is convinced that a well-rounded liberal arts education by itself isnt enough to germinate budding musical careers.

“Theres always a lot of great [young] talent stepping up to do concert music. The problem, of course, is the talent level is far beyond any realistic financial opportunity,” Harbison says. “Theres an artistic force driving a lot of people to engage in an art that doesnt offer much [in terms of] logistical prospects. I can sympathize with a lot of parents who are alarmed by it.”

Preserving Concert Musics Appeal

A prolific worker whose earliest compositions date back more than 40 years, Harbison is still driven to produce. “Theres always more of an urge to go and do something else,” he says. “Quite naturally, by having written one piece, its almost like Im playing a chess match with myself. I want to make another move, that either furthers the enterprise, or counters it.”

He is also constantly pushing the musical boundaries. “I try to keep moving, and not be bound by what is expected,” he explains. The expectations keep shifting as well, he believes, as the audience changes, and technology expands its reach into the musical world. “[The styles] have changed very much with drastic new elements coming in and departing. The turnover of both the significant changes and the fads is faster.”

Despite the changes, Harbison believes concert music can retain its limited, albeit indelible impact on society. “The issue isnt how many people are there or how many CDs are sold, but it has to do with among the people who are interested how concerned they remain, and how intense their interest is,” he says.

Certainly, Harbison believes, concert music must “become more visual” to preserve its appeal, perhaps through its growing link with opera, and certainly through its ability to affect young people. And that is where ARTS FIRST 2000, and other programs like it, enter the picture.

“Its a wonderful idea, because the more broad the involvement is, and inclusive, the more everyone shares some sort of an experience,” Harbison says. Its that shared experience that may foster future symphonic musicians, composers, and audience members. “I think weve hit the bottom point, and weve begun to move up and out, and for concert music, the consequences will be a ways off, but theyre very heartening.”