Scans Predict Alzheimer’s Risk

Older people frequently forget where they left their glasses or parked their car. Could such memory lapses be a sign of Alzheimers disease? Until now, no good way existed to discriminate normal failures of memory from the approach of the dreaded malady that robs elders of their personalities.

That situation has begun to change. Using readily available brain scanning techniques, researchers at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital have identified telltale brain shrinkage that presages Alzheimers. They distinguished between people considered normal and those with memory problems that progressed to Alzheimers with 93 percent accuracy. For those with memory problems who went on to develop the disease within three years, versus those with problems who have not gotten the disease, accuracy reached 75 percent.

“Were very gratified by these findings,” said Marilyn Albert, professor of psychology at Harvard and leader of a team that includes investigators from Brandeis and Boston universities and Brigham and Womens Hospital. “However, before any test based on these findings can be used on an everyday basis, we must improve accuracy. While we do this, others are making significant headway toward effective drug treatments. We hope to be able, in the next decade, to identify those people who can benefit most from such treatments.”

At present, physicians live with the frustration of not being able to provide much help to people diagnosed with Alzheimers. Things should change dramatically if the disease, like cancer, could be identified in its earliest stages and treatments begun as soon as possible.

The same brain scans that find the disease could also be used to determine the efficacy of treatments to control it. For example, does a particular drug lessen, or even prevent, brain shrinkage?

Neil Buckholtz of the National Institute on Aging noted that these research results offer “evidence establishing the involvement of certain areas of the brain in the early pathology of Alzheimers disease. It also suggests that, by zeroing in on these areas, we may be able to better identify people at greatest risk and those for whom early treatment could make a difference.”

Measuring Brain Shrinkage

Albert and her team compared 119 people, 24 without memory difficulties, 79 with mild memory problems, and 16 with early Alzheimers. The investigators followed the first two groups for three years, then compared them with those who already had the disease to determine if they could predict who would develop full-blown Alzheimers. The latter accumulate sticky plaques and fibrous tangles in their brains, which kill nerve cells and cause shrinkage of tissue.

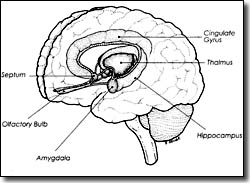

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), they found early changes near the hippocampus, a bean-sized organ in the middle of the brain, not far above the top of the spinal cord. A tiny area connected to the hippocampus, and known as the entorhinal cortex, was 37 percent smaller in those who developed Alzheimers than in normal subjects. The entorhinal cortex is involved in remembering, which ties in with the fact that Alzheimers patients suffer progressive memory loss.

Another suspect area, called the superior temporal sulcus, appears to be necessary for holding information during a time delay, as when you look for a pencil to write down a telephone number you have just heard. Damage to this area apparently impairs attention span and normal memory.

Soon after these parts begin to degrade, shrinkage occurs in a band of tissue called the anterior cingulate gyrus, which lies slightly above the hippocampus. It connects via numerous nerves to the front of the brain where decisions about organization and planning are made. Those connections also fit well with Alzheimers symptoms of confusion and inability to plan, which often follow memory difficulties.

“We believe that people cross the line between memory impairment and Alzheimers disease when brain-cell loss spreads to the anterior cingulate gyrus,” Albert states. “But thats a theory that has yet to be proven.”

Details of this research were first reported in the April issue of the Annals of Neurology.

Putting It All Together

“There are more brain areas we can measure to help us determine how the disease spreads,” Albert says. “Finding such areas should improve the accuracy of determining which people with memory problems go on to get Alzheimers and which do not.”

To this end, the investigators also do other tests. These include brain scans that reveal functional abnormalities in the brain, such as patterns of oxygen use. MRI picks up only structural peculiarities, such as shrinkage. Overlaying structural and functional images should produce a clearer picture of what goes on during the early stages of Alzheimers

Researchers also investigate deposits of plaque that clog the processes of thought by killing brain cells. These plaques contain a toxic form of a protein called amyloid, presence of which can be monitored by a blood test.

“For a long time, we thought we could come up with the test to tell us whether someone will or wont get Alzheimers,” Albert notes. “But the consensus now is that it will be a combination of tests. Adding together all the measures we now have could give us higher accuracy than MRI scanning alone. But this cannot be done yet on a daily basis in a doctors office. It would be too time-consuming and expensive.”

When Albert and her colleagues started their study, they thought they could determine who would get Alzheimers from comparing normal people with those having a mild form of the disease. As the brains of the former group started to look like those of the latter group, all the information needed to diagnose questionable cases would be there.

“Things turned out to be enormously more difficult than that,” Albert admits. “Some people with progressive memory problems develop the disease, but others dont, even if they have a lot of difficulty. In fact, we were surprised at how few people (19 out of 79) did go on to full-blown Alzheimers. We expect that more of the questionable people will develop the disease, and its frustrating not to be able to say who they will be.”

New drugs in various stages of testing are making Alzheimers experts more optimistic than they have been in years. The National Institute on Aging intends to use MRIs to test the usefulness of one of these drugs (donepezil) and of vitamin E to slow or stop the conversion of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimers.

“The hope is that our ability to discriminate people who are destined to develop the disease will closely coincide with the approval of more efficacious drugs,” Albert says. “Then wed have something to offer those who can benefit most from that help.”

In the meantime, prediction work goes on, but slowly. “Were finding that the people we follow change much more slowly than anticipated,” Albert says.

Also, the surprising variability among people makes prediction very difficult. To cover such variability, the research team is looking for more volunteers to participate in the study. Those who are interested must be 65 years or older, have mild progressive memory problems, and be in close touch with someone who knows of their problem and sees them often. Please call (617) 726-5571 for more information.