Afro-Am Celebrates 30 Years

Founders and graduates of Harvards Afro-American Studies Department came together last weekend to reflect on the struggle that gave the department birth, to plot strategies for the future, and to praise the dream become reality.

“None of us who were there at the beginning of this can be anything but proud,” said Jeffrey Howard, a 1969 graduate, former chair of the Association of African and Afro-American Students, and a member of the Ad Hoc Committee of Black Students whose negotiations with University officials led to the Departments creation. “Harvard is the center of Afro-American studies in this country. This is precisely what we envisioned in 1969. We envisioned, you [who followed us] delivered.”

Howard was one of the closing speakers Saturday at a daylong conference that marked the 30th anniversary of the Departments creation. The conference was part of homecoming ceremonies that attracted hundreds of Harvard students, graduates, activists, faculty, and others interested in Afro-American studies.

The Homecoming weekend was also the occasion for the announcement of the first Afro-American studies chair endowed by a corporation. Called “The Quincy Jones Professorship of African-American Music, Sponsored by the Time Warner Endowment,” the professorship was announced Friday evening. It was created by a gift from Time Warner Inc. to further research and teaching in African-American music.

The chair is named after famed musician, producer, and artist Quincy Delight Jones Jr., who attended a Friday evening dinner in Boston where the new chair was announced.

Saturday proved a day of both reflection and celebration, as different panels examined subjects including Americas racial divide; African-American women, music, religion and art; and the Departments past, present, and future.

Department Chair and W.E.B Du Bois Professor of the Humanities Henry Louis Gates Jr., widely credited with attracting the nations top scholars in Afro-American studies to Harvard, thanked a long list of the Departments benefactors. Among them were student activists who pushed for its creation, past department chairs, faculty, staff, and others instrumental in the Departments creation and growth.

Several key players, including the students who pushed for the departments creation and two faculty who served on the committee that recommended its creation, Thomson Research Professor of Government Martin Kilson and Geyser University Professor, Emeritus, Henry Rosovsky, were honored with W.E.B. Du Bois medals, created for the occasion.

Gates credited Harvard President Neil L. Rudenstine and Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Jeremy Knowles with providing the critical administrative backing necessary to pursue top scholars. Rudenstine, who delivered the conferences opening address, said the Homecoming celebration was one of the high points of his career as an administrator.

In his speech, Rudenstine used his own life experiences to illustrate how far American society has come in its awareness and treatment of African-Americans. He detailed his days as a student at an all-white secondary school virtually unaware of black America and of his gradual recognition of this critical portion of American society.

“Schools left us knowing little but we, in honesty, didnt reach out to find out more,” Rudenstine said. “Ignorance there was, but there was also a devastating blindness.”

But in highlighting how far the country has come, Rudenstine also said that there remains much work to do to ensure equality among all groups. Harvards role, he said, will be to create new knowledge about current and past conditions through research and to create future leaders through education.

“The task never ends. There is always so much more to do,” Rudenstine said. “There is still ignorance and blindness and too often the pathology of hate to be overcome.”

Rudenstine ended his speech by pledging that Harvard will craft a diverse student body by continuing “to take into account ethnicity and race, as well as other factors, when it admits students to this University.”

History Redeemed Or Not

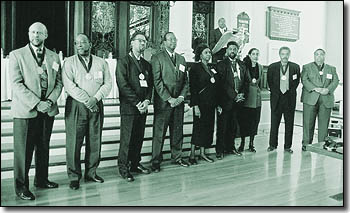

The racism and blindness to injustice were not always kept at bay by the walls of Harvard Yard. Nine of the 17 African-American students who sat on the Ad Hoc committee which negotiated the Departments birth returned Saturday to share their memories of the past and thoughts of the future.

Some said the changes since the Departments creation and its current prominence, on display last weekend, showed that the darker past has changed.

“I was struck by how much history has been redeemed,” said Lee Daniels, who graduated from Harvard College in 1971 and who is a former fellow of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research, which marked its 25th anniversary Saturday.

Others debated whether or not history had been redeemed, or even recounted accurately. Through the course of the day, several called for a new effort to record the events that led to the Departments creation.

Octavia Hudson 71, a member of the student Ad Hoc Committee and today a television producer, director, host, and screenwriter, said she recalls being pessimistic about the Departments future even after having won its creation. That pessimism has since lifted.

“We felt we won the battle, but lost the war,” Hudson said. “Now I see maybe we didnt lose the war after all.”

Memories of the past were not all pleasant. Some, including Robert La Bret Hall, chair of the African-American Studies Department at Northeastern University, spoke of encountering racism on campus, from faculty as well as students. Others spoke more generally of feeling alienated, of being “at Harvard, but not of Harvard.”

Jeremy Knowles, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, addressed the past in his speech Friday evening at the dinner opening the Homecoming event. Yes, Harvard, admitted black students before the 1960s, he said, but Harvard also reflected the attitudes and biases of its times.

“The truth is that for every Du Bois who came to Harvard to complete his education, there were many thousands who never made it to Johnson Gate, and still less walked through it,” Knowles said. “The truth is, that for much of the 20th century, a university publicly known for its tolerance was often privately intolerant; not only in obvious ways, such as the embarrassing attempt to exclude African-Americans from the freshman dorms in 1922, but in the quiet complacency that survived well into most of our lifetimes, and that was only partially removed by the events of 1969.

“For all the controversy of those angry days and the bruised feelings that were left on all sides, the creation of the Department reminded us that moving forward doesnt threaten the University, its what universities must do.”

Geyser University Professor Emeritus Henry Rosovsky, who chaired the Faculty committee studying whether to create the Afro-American Studies Department, said the times were trying and mistakes were made by both the students and the University. But the Department that resulted from their labor is just beginning to bear fruit.

“I truly believe that we aint seen nothing yet,” Rosovsky said.

Future Perfect?

Though many hailed the progress made in 30 years, some wondered if the Department is divorced from the realities facing African Americans today. Others, however, said the Departments academic and scholarly role is rightly one of research and leadership and doesnt mean it is out of touch with the African-American community.

“It seems to me that the African Americans around this country who are mired in poverty, without hope, without a shred of self-respect, deserve to know that in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at Harvard University, theres a faculty that cares about them,” said Ruth Simmons, President of Smith College, who delivered one of the closing speeches.

Still others criticized the Department for being slow in hiring women faculty, despite women making up three of the four recent junior faculty appointments.

In the days keynote speech, Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor Cornel West outlined a vision of the future where the Department helps “strip America of its innocence,” and of “white supremacist lies.”

That future wont just be a struggle for greater equality, West said, it will also have to guard against the loss of todays hard-won gains. Pressing needs and disturbing trends clamor for attention, he said, such as the increasing incarceration rates of young African-American men and the problems of drug addiction, suicide, homicide, and police brutality.

Solutions to these problems will have to be crafted against a backdrop of an increasingly globalized economy, the worldwide spread of modern American culture, and an influx of new immigrants that is changing the nations ethnic balance.

“How do we keep alive a sense of hope?” West said. “Because if all we can offer the next generation is some flattened American version of optimism, they ought to reject it. A generation satisfied with material toys is not what they had in mind.

“Can we meet the challenge?” he said. “We shall see.”