College Students Binge More Frequently, Survey Finds

College students are drinking more and college administrators are enjoying it less, according to a nationwide study of binge drinking.

College students are drinking more and college administrators are enjoying it less, according to a nationwide study of binge drinking.

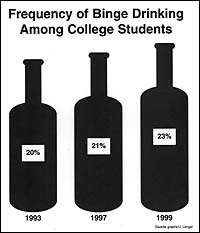

Approximately one in four (23 percent) of more than 14,000 students surveyed admitted to frequent binge drinking, defined as consuming four, five, or more consecutive drinks at least three times in the two weeks prior to filling out a questionnaire. Thats up from about one in five (20 percent) in 1993. The increase was greatest in the years between 1997 and 1999, a time of increased national focus and efforts by college administrators to address the problem.

“It is disturbing that these findings show an increase in the most extreme and high-risk forms of drinking,” says Henry Wechsler, director of the College Alcohol Study conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health.

For men, binge drinking is defined as downing five or more consecutive drinks. For women, drinking four or more drinks in a row is considered bingeing. Approximately two of every five students (44 percent) admitted to at least that much drinking, about the same as in 1993 and 1997.

“Research shows that females have the same rate of problems on four drinks as males do on five,” Wechsler said. “Thats probably because they have a lower body mass and metabolize alcohol more slowly.”

Results of the study were released on Tuesday, March 14. The survey involved students from 119 four-year colleges in 39 states.

Harvard was not included in the research. However, a 1997 survey revealed that Harvard students went on drinking binges somewhat less than the national average; 37 percent binged and 19 percent binged frequently. “That can be explained by the admission of a larger number of freshman who did not binge in high school,” Wechsler says.

Another study that followed Harvard graduates for 60 years concluded that those who abused alcohol started drinking later but were only half as likely to quit as a comparable sample of inner-city men, most of whom didnt go to college.

Nondrinkers Add Balance

Wechsler noted that the bad news about bingeing “is, in part, counteracted by a larger number of abstainers.”

Nondrinkers among college students increased from 15 percent in 1993 to 19 percent in 1999. In other words, while one in four students is a frequent binge drinker, almost one in five doesnt drink at all.

Furthermore, one-third of students who live on campuses do so in alcohol-free dormitories and residence halls. Another 13 percent (about 1,800 of the 14,000 polled) said they would like to live in such housing.

The survey emphasized that housing plays a key role in bingeing. In fraternity and sorority houses, an average of three of every four students are binge drinkers. And, while binge drinking rates decreased by almost six percent among students who live in college dormitories, they increased by about the same amount among those living off-campus.

In a report published in the March issue of the Journal of American College Health, Wechsler and his colleagues note that binge drinkers have more problems than non-binge drinkers. These problems include missing classes, falling behind in schoolwork, arguing with friends, damaging property, engaging in unplanned sex, having unprotected sex, becoming injured, and driving while drinking.

The binge drinkers also give a lot of headaches to students who drink less or not at all. The latter complain of losing sleep, insults or humiliation, unwanted sexual advances, sexual abuse, and date rape.

“People say, well, sexual abuse and date rape involve only one or two percent of students,” Wechsler notes. “But were talking about more than 3 million females.”

Previous research shows that binge drinkers dont think they have a drinking problem. “They consider themselves moderate drinkers and say they can handle 10 drinks,” Wechsler notes.

Sobering Strategies

According to a second article written by Harvard researchers in the same issue of the Journal of American College Health, administrators at 97 percent of 734 colleges polled reported having alcohol education programs on their campuses. But, only 40 percent of schools have a cooperative agreement with community agencies to address excessive and underage drinking, and only 24 percent meet regularly with community groups to address such issues.

“There is some indication that on-campus programs might be having an impact,” Wechsler comments. “But this is offset by the off-campus drinking environment where there is a ready supply of low-cost alcohol. We need to focus attention not only on teaching students to be responsible drinkers, but also on getting stores and bars to be responsible servers.”

In one example of off-campus influences, the Student Government Association of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, petitioned the school to raise the limit on beer allowed in dormitory rooms from 24 to 30 cans. The reason, said the students, was that stores now sell cases containing 30 beers. The administrators announced their agreement to the change one recent Friday, but by the following Monday the decision was reversed.

Pressure to drink more can come from unusual sources. This week, the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) launched a St. Patricks Day campaign urging students to switch from milk to beer. To show they were serious, the group gave away free bottle-opener key chains. “Save a cows life,” the opener pleads on one side. On the other side it says, “Drink responsibly. Dont drink milk.”

One researcher at the press conference, who didnt want to be identified, said he thinks its an absurd idea. “What about all the dogs and cats those binge drinkers will run over?” he asked sarcastically.

Asked his opinion, Wechsler laughed for a while, then quipped, “Im sure they werent under the influence of milk when they had that idea.”