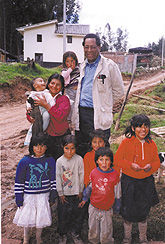

Children Treated for Lead Poisoning

The man brought his 9-year-old son into the makeshift clinic to test the boys brain.

There was no point in doing even the simplest test, the nurse noted. The boy was so retarded he didnt know his own name, and he walked with a shuffling gait produced by severe brain damage.

Allen Counter, an associate professor of neurology at Harvard University, looked at the boys teeth. He immediately saw the horizontal black lines that signal lead poisoning.

” I have two others at home like him,” the man said.

“Do you think the lead has done this to them?” Counter asked.

“I am sure of it,” the man replied.

“Why didnt you bring your sons in before?”

The man shrugged. He lived in the mountain village of La Victoria in central Ecuador, where he and his family supported themselves making roof tiles glazed with lead extracted from discarded truck batteries. Its a cottage industry that involves whole families, including young children, and it pollutes the surrounding air and earth with particles of lead from kilns where the tiles are glazed. The particles also rain down on small farms nearby, contaminating vegetables and grains that families grow for food.

” Lead poisoning in such villages is the most extreme my colleagues and I have seen,” Counter comments. Blood tests revealed lead levels three and four times those that would call for immediate hospitalization in the United States.

Finding other ways to make a living, however, is difficult if not impossible for these people, mostly impoverished Quichua Indians. Companies that profit from their labor discourage complaints about exposure to the dangerous metal, and resent interference from strangers seeking to advise them of the hazard.

While doing biological and anthropological studies of Indian and African people in Ecuador, Counter heard many medical complaints from those who work with lead. With help from colleagues at the University of San Francisco, he collected blood samples, administered psychological tests, and made recordings of brain-wave activity of children in several villages.

” While some of them show remarkable resistance to lead poisoning despite high levels of the metal in their blood, we found irrefutable evidence of brain damage and neuromuscular abnormalities,” Counter says. “I became determined to do something about it.”

Efforts to Help

Villagers and village leaders have held s protest in the capital city of Quito. Parents and teachers complained of the learning problems suffered by the children, but to no avail. The troubles of poor, rural minorities are not a priority for the government. Recently, the Indians played a major role in unseating the countrys President, Jamil Mahaud.

To press the lead issue, Counter, with the help of Fernando Ortega of the University of San Francisco, organized a seminar to which he invited Ecuadors Minister of Health, Gonzalo Baquero. The Minister agreed that something should be done and promised to establish a childrens day-care center in La Victoria.

The center opened in the fall of 1999 and now provides a way to remove children from much of the lead-glazing work. An education program has also been initiated to warn villagers of the continuing dangers of working with lead. To help adults, Counter, Ortega and others spent their own money buying masks that workers can wear to filter lead from the air.

In the United States, many children get lead poisoning from eating paint chips in older dwellings painted before lead-containing paint was outlawed in 1960. The paint and putty have a sweet taste. Such youngsters are treated with so-called chelation drugs that leach lead from their bodies.

Counter consulted experts at Harvard-affiliated Childrens Hospital in Boston, and they recommended a drug known as succimer for treating children in Ecuador. The drug produces no harmful side effects but is expensive, about $400 for a bottle of 100 pills.

Lacking money, Counter wrote letters to various drug companies asking them to donate the medicine. It seemed like a long shot at first, but then Sanofi Pharmaceuticals of New York City agreed to provide $20,000 worth of Chemet, Sanofis brand name for succimer.

Overjoyed, Counter worked with Michael Shannon, associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, to determine what dosages would give the best results. By last November, he was ready to fly to Quito.

Volcanoes Get in the Way

At about the same time, however, the volcano Pichincha erupted in Ecuador. The eruption darkened skies over Quito with clouds of ash, and Counter was advised not to come. He rescheduled the trip later in the month, but another eruption made it too dangerous for planes to land.

Finally, the skies cleared enough for Counter to reach Quito and La Victoria on December 11. With the help of Ortega and two doctors, Sonia Lopez and Mirian Hidalgo-Vaca, the medicine was distributed to those who needed it. As they worked, they could see smoke belching from a second volcano, Tungurahua, within sight of La Victoria.

Speaking for parents in the village, one woman told the doctors: “This is the best Christmas present that we could have received for our children.”

When he tells the story, Counter describes it as a team effort. He cites those who analyzed the blood and brain tests: Diana Rosas of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Howard Hu of the Harvard School of Public Health, and Nader Rifai of Childrens Hospital. He also praises the efforts of Leo Buchanan and David Rosenthal of the Harvard University Health Services who did other medical analyses and stored the Chemet while he waited out the volcanoes.

The whole story is yet to be told. Jamil Mahaud, president of Ecuador, has promised to cooperate with Counters group to help Indians in other rural villages that depend on working with lead for a livelihood. Alternatives being looked into include using a nonlead glaze for the tiles they make, and growing flowers to sell.

Another problem Counter wants to take on involves mercury poisoning among families who use the liquid metal to process gold ore. Saraguro Indians working in gold mines bring small amounts of the ore home to their wives and children. The latter use mercury to amalgamate or remove tiny flecks of gold, then the mercury gets burned-off, leaving the behind the gold. This processing is usually done inside houses and huts, exposing women and children to mercury vapors. Such exposure can lead to problems that include tremors, numbness, delirium, memory loss, kidney failure, and even death.

“Mercury poisoning can be treated with drugs like Chemet,” notes Counter, who is also director of the Harvard Foundation, an organization that promotes intercultural and race relations. “It is a growing problem among the poor in many areas of South America. Perhaps we can help reduce it in the same way lead poisoning is being reduced.”