Robin Bernstein.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

Robin Bernstein was looking for something else when she stumbled on a bit of information about a murder in 19th-century upstate New York.

That accidental discovery served as inspiration for “Freeman’s Challenge: The Murder That Shook America’s Original Prison for Profit,” a new book by the Dillon Professor of American History and chair of the American Studies program.

At the center is William Freeman, a mixed-race African American and Indigenous man convicted of horse thievery in 1840. Sentenced to five years of hard labor at Auburn State Prison, Freeman was forced to manufacture goods for various private entities.

Upon his release, he set about campaigning for back wages. When that failed, he lashed out with a grisly crime that would help shape how Americans came to think about race, criminality, and imprisonment.

The Gazette caught up with Bernstein, also a professor of African and African American Studies and of Studies of Women, Gender, & Sexuality, to learn more about this previously unexamined history. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Where did you find the story of William Freeman?

It was in a footnote. There, I came upon an 1846 theatrical show about how William Freeman murdered four white people, including a toddler and a grandmother.

One of my areas of expertise is theater history. I knew it was nearly unheard of at mid-19th century for a show to depict Black-on-white violence. At the time, even performances of “Othello” took great pains to avoid it, because white people did not want to see it.

I asked myself, “Why were these white people in Auburn, N.Y., behaving so differently from white people across the nation?” I knew something amazing had happened, and I had to learn what it was.

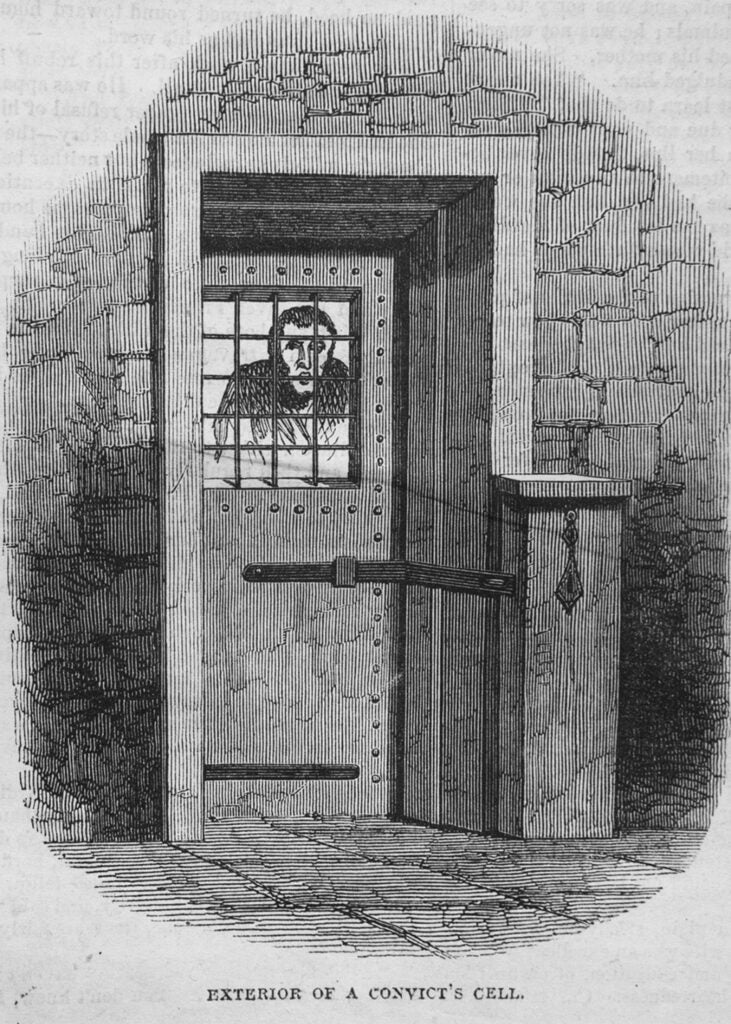

Exterior of a convict’s cell at Auburn State Prison.

Harper’s Weekly, 18 December 1858, 809.

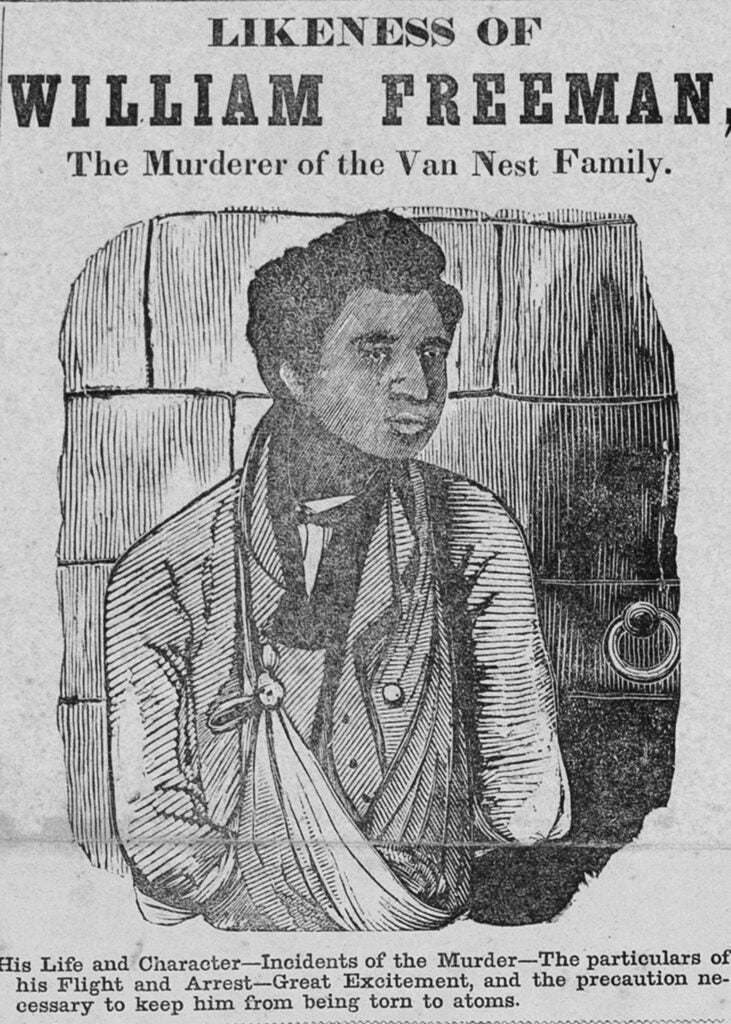

Rendering of William Freeman, Daily Cayuga Tocsin — Extra, 19 March 1846.

William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

So how did Freeman initially land in prison?

Freeman was from a family that had just completed the process of gradual emancipation and named themselves Freeman. The name speaks to who they considered themselves to be — and what future they were choosing for themselves.

When Freeman was 15 years old, a horse was stolen. He was accused. There was no physical evidence against him, but it didn’t matter. He was tried and convicted and sentenced to five years in the Auburn State Prison, where he was subjected to convict-leasing. He was forced to manufacture animal harnesses and dyes and carpets, all of which were sold by private companies.

Freeman was furious at being forced to labor, as he put it, “for nothing.” By nothing, he meant no crime — because he always insisted he was innocent of the horse theft — and no pay. He was explicit about both of those meanings. He considered himself a worker, not a slave.

I understand that Auburn State Prison was itself an innovation.

The Auburn State Prison is very important, because it originated prison-for-profit. It originated the idea that a prison could function primarily to generate wealth rather than control or punish or rehabilitate criminals.

There’s a common perception that profit-driven convict leasing was invented by the South after the Civil War, as part of a white effort to re-enslave African Americans. But my book reveals how the North invented this system half a century earlier, in the wake of Northern, not Southern, slavery.

The Auburn State Prison opened in 1817. By the 1840s, it was an economic force throughout New York State. Meanwhile, the Auburn System, as it was called, was being exported. There were many dozens of prisons being built on the Auburn System all over the United States and Europe. San Quentin, for example, would soon be built on Auburn’s model.

Your book details Auburn State Prison’s innovations in another area: violence. What kinds of violence did Freeman experience there?

One of the central forms of violence was extreme social isolation. The Auburn system involved each prisoner being sequestered in solitary confinement every night. During the day, they worked in factories that were built into the prison, but they were forbidden from ever speaking.

While Freeman was incarcerated, a prison administrator invented a machine for waterboarding. Freeman was waterboarded, but he was also whipped and flogged. At one point he was beaten with a board that split on his head and he suffered a brain injury. He also became almost completely deaf.

I find it interesting that Freeman never sought a legal remedy for his physical injuries. He focused exclusively on back wages.

It was legally possible to sue for injury at the time, but he never tried. When he got out, in 1845, he tried to collect what he considered back pay. He appealed to magistrates. He was laughed at and dismissed. And then he committed an act of terrorism that was a strike against the state, a strike against the system of prison-for-profit.

Freeman stabbed to death four members of the Van Nest family in their home within hours of seeking back pay for the last time. I hesitate to rehash the details.

What was most important to me was not the blow-by-blow of how Freeman killed the family, but rather how he described it: He called it “work.” That tells us what is at the core of his concern. He had been forced to work in prison factories for no pay, and now he extracted “payback” through a murder that he called “work.” It was an immense irony.

Let’s move on to the murder trial. It was a high-profile case and the two lawyers involved were significant historical figures. Who were they and what did they argue?

Twenty years after the trial, William Henry Seward became Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, which is what he’s most remembered for today. He’s also remembered for brokering the purchase of Alaska — if you’ve ever heard of “Seward’s Folly.”

At the time of the trial, in 1846, he was a recent past governor of New York state. He was living and working as a lawyer in Auburn and decided to take Freeman’s case pro bono.

Seward argued that Freeman was insane, and that he committed the crime because he was insane, and that he became insane as a result of racism. Seward was not ventriloquizing arguments that were already widespread. He was crafting them. Seward basically made the social pathology argument that [Assistant Secretary of Labor under President Lyndon B. Johnson] Daniel Patrick Moynihan would make a century later [in his 1965 report on Black poverty].

It’s an argument that continues to have enormous purchase today. And let’s name it clearly: It is a racist argument that criminalizes Black people.

Who was Seward’s adversary, and what did he argue?

The prosecution was led by John Van Buren, who was the son of recent President Martin Van Buren. What we know right away is that this was a clash of the titans. This was a former governor versus the son of a president and a grisly crime, an enormously disturbing crime. Newspaper readers across the nation were riveted.

Van Buren made a different racist argument. His argument was that Freeman committed this murder because of inherent racial savagery. In different ways, Seward and Van Buren were both arguing that Freeman committed these crimes because he was Black and Native American, which is completely contrary to everything that Freeman ever said. Freeman said that he did it because his wages were stolen from him by the emerging system of prison-for-profit.

Why did nobody hear what Freeman said about his actual motive?

On some level, they did hear it. They were just enormously threatened, the white population in particular. We need to understand Auburn as a kind of company town. Every person, every business, every physical aspect of the town was connected to the prison. So people had an economic interest in protecting it. The fact that they went to such lengths to invent other reasons for Freeman’s crime, that tells us how hard they were working to not hear what Freeman was saying.

Auburn later emerged as a hub of abolitionist thought. Was there any connection to Freeman?

It’s worth mentioning that the Black community also felt threatened, but for different reasons. Their problem was, how to live in a world in which Freeman had committed these crimes, and how to live with the racist libels that the trial developed and unleashed.

One of the answers became activism. One of the arguments Seward made in court was that Freeman committed his crime because he had been excluded from white schools — and there were no Black schools in Auburn. Afterwards, the Black community very cannily raised money for Black schools.

Also striking was that prior to Freeman’s trial in 1846, there was very little abolitionist activity in the town. All of a sudden, after the trial, Black abolitionist lecturers including Frederick Douglass and Henry Highland Garnet become very interested in Auburn.

The first edition of “Twelve Years a Slave” [1853] by Solomon Northup was published there. The first edition of Douglass’ “My Bondage and My Freedom” [1855] was published there. And then Harriet Tubman moved to Auburn — she spent the second half of her life there — and the first edition of her dictated autobiography [1869] was published in the town.

I understand this as a strike against the trial. Freeman was silenced; he never took the stand. His actual argument was buried under the narratives Seward and Van Buren invented and amplified. So how did Black communities respond? They responded by telling their own stories.

Robin Bernstein will be joined by Brandon M. Terry, John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Social Sciences, to discuss “Freeman’s Challenge.” 7 p.m. Friday (May 17) Harvard Bookstore.